Unseen Design: How We Underestimate the Tangled Wisdom of the Human Throat

Jonathan Reisman on the Complicated Wonders of Anatomy

When I first studied human anatomy in medical school, one body part in particular seemed rather stupidly designed: the throat. Our throats are where swallowed food and inhaled air, after entering the body through the same mouth, diverge into their respective tubes—the esophagus and windpipe. In the throat, the esophagus’s entrance for swallowed food lies immediately behind the windpipe’s for inhaled air, like two straws with their open ends abutting each other and only a few scant millimeters of tissue dividing them. Diagrams in my medical textbook showed the details of the throat, or pharynx, an all-important intersection where, with each and every swallow, food and drink careen directly over the windpipe’s entrance, coming within a hairsbreadth of slipping in. One tiny lapse could cause choking, suffocation, and death.

The throat’s perilous construction stood in stark contrast to the brilliant design of other body parts I had been learning about. The human hand and forearm, for instance, possess a wondrously dexterous architecture of bones, muscles, and tendons with the staggering ability to grasp tools or play jazz piano. And with equal elegance, the perfectly synchronized cooperation of heart and lungs delivers oxygen to all the body’s distant crevices. Anatomical mechanisms always seemed intelligent, to favor life and enhance survival—but not the throat. When my anatomy professor joked about the “idiotic” arrangement of the human pharynx, I chuckled along with my fellow students.

But years later when I worked as a hospitalist—a doctor working exclusively with hospitalized patients—a significant proportion of my job consisted of battling the fallout of the throat’s flawed design, and I found little to laugh about. I frequently treated old and infirm patients suffering from aspiration, the medical term for food going down the wrong pipe. Aspiration can involve choking on large chunks of food that suddenly suffocate all of the windpipe’s airflow, but most of my patients were aspirating only tiny amounts of food, drink, and saliva. Instead of choking all of a sudden, this process occurred slowly but consistently over weeks and months—and often went unnoticed by patients or their caregivers. For them, the throat’s failure to keep food and air separate caused breathing troubles, frequently landing them in the hospital under my care and compounding my bewilderment at the throat’s tangled anatomy. But one elderly patient, Suzanne, ended up forever changing the way I thought about this body part.

*

Suzanne was an 82-year-old woman who lived in the suburbs of Boston. She had worked her whole life as a seamstress and did not give up her career until her late seventies, when her health began to decline. She resisted the ebbing of her independence, and when her daughter, Debra, tried to move her into a nursing home, she refused. Suzanne’s physical deterioration quickened, and she had several falls, but thankfully no broken bones. Debra hired visiting nurses to care for her mother in her own house, but mental decline soon came as well, stripping Suzanne of a lifetime of memories and the ability to form meaningful sentences. When caring for her at home became too difficult and unaffordable, there was no choice left but to move her to a nursing home.

I met Suzanne a month later, when she was admitted to the hospital for a mild case of pneumonia. She recovered over a few days of antibiotic therapy, and I discharged her back to the nursing home.

But a few weeks later, she was back again with a second (and more severe) bout of pneumonia. I visited her in the emergency room (ER) while she was waiting for a bed on the medical ward, and I found her lying on a cot, struggling weakly against padded wrist restraints that kept her from pulling off her oxygen mask. She had the same toothy grin and gray frazzled hair, but she looked thinner and more malnourished than during the first admission—her temples were sunken and wasted, her ribs prominent and heaving with each strained breath.

“It’s Dr. Reisman again. Did you miss me?” I joked. She mumbled something incomprehensible, which I could barely hear over the hissing flow of oxygen and the rattling of phlegm caught in her throat. She seemed less alert than when I discharged her last—pneumonia had once again tipped her fragile mind, already demented by Alzheimer’s, into further confusion and disorientation. I listened to her lungs with my stethoscope and heard the sound of bubbles blown through thick porridge.

Like many other patients I have treated for aspiration, Suzanne’s decline began with coughing at meals. Before that, her mental deterioration and advancing dementia had proceeded steadily, but when the coughing started, her weight began to drop and her physical and mental debility accelerated. During her previous hospitalization for pneumonia three weeks earlier, I had discovered that she was aspirating while eating—this was the reason for her cough.

The root of Suzanne’s problem lay in the mechanics of her swallowing. Though it is casually performed hundreds of times each day by all our throats, swallowing is no simple feat. Maneuvering food and drink safely past the airway’s entrance requires an intricate neuromuscular orchestra of contractions and contortions of the tongue, palate, pharynx, and jaw. Food approaches the windpipe as we swallow, and just as suffocation seems imminent, several different muscles coordinate to lift up the windpipe’s top end, the larynx. This timely gesture is visible from the outside as the Adam’s apple jerking upward, as it tucks the airway’s exposed opening under the tongue, sealing it closed against the epiglottis, a firm flap of tissue that perfectly plugs the larynx like a manhole cover. Food and drink can then safely sidestep the airway, traveling beyond it and into the esophagus. Once the coast is clear, the larynx lowers again and settles halfway down the neck.

Swallowing involves the cooperation of five separate cranial nerves and more than 20 different muscles. This complicated mechanism is the body’s attempt to compensate for the throat’s inherently dangerous anatomy, but it is a clunky and overly complex solution to a serious problem, and therefore prone to failure. This is especially the case when people talk while eating, an attempt to keep both the esophagus and the airway open at once. It is no wonder that so many people choke to death every year.

To top off all of the throat’s dangers, the number one pneumonia causing strain of bacteria in the world lives in the back of the human throat, just above the airway’s opening. Poised there much of our lives and forever ready to slip into the lungs, these bacteria wait for the moment the airway’s guard is let down. For healthy people, the situation poses little danger, as these infectious barbarians are handily and thoughtlessly kept at the gate. But for Suzanne, dementia had stripped her defenses, progressive debility had weakened her throat muscles, and neurologic decline had distorted her swallowing’s coordination. Even her gag reflex—the throat’s instinctive rejection of anything besides air headed for the windpipe—was weak and ineffectual.

She ended up in the hospital a second time because the bits of food and saliva she was aspirating had once again brought bacteria from her throat down into her lungs, where they festered and thrived, blooming into another “aspiration pneumonia.” This condition is exceedingly common in Alzheimer’s patients like Suzanne, as well as in those suffering from other neurodegenerative diseases like strokes and Parkinson’s disease. I have seen the same infection also result when patients aspirate during a seizure or in a drug- or alcohol-induced stupor.

I examined Suzanne each day during my rounds—the early-morning task of seeing all my hospitalized patients one after the other. I placed my stethoscope against the thin freckled skin over her back and listened to her lungs, and I monitored her mental status. I knew that the next aspiration event was an ever-present possibility and could result in another pneumonia or the need for an emergent breathing tube. Or it might quickly suffocate and kill her. Because of this dangerous quirk of human anatomy, the risk of further deterioration for my patients was highest precisely when things were most tenuous.

It seemed an unfair, and rather unintelligent, design.

Anatomical mechanisms always seemed intelligent, to favor life and enhance survival—but not the throat.

Over the next three days, Suzanne’s breathing improved with antibiotics, and she was able to wean off supplemental oxygen. Each morning, I noted a gradual clearing of her breath sounds, and her mental status returned to her baseline—she was still confused and uncommunicative, but slightly more awake and alert. I worked with consultants from the speech and language pathology service to reduce her aspiration risk: we avoided giving thin liquids like water and juice, which easily evade the guarding epiglottis, choosing instead only thicker consistencies that her clumsy throat could more easily shepherd into its proper avenue, the esophagus.

One day I chatted with Debra at her mother’s bedside after finishing rounds, as a hospital health aide slowly spoon-fed Suzanne a lunch of oatmeal and thickened liquids. I explained, as I had to the families of many similar patients before, that the aspiration risk could never be completely eliminated. We could bypass her mother’s throat altogether, and feed her instead with a tube permanently implanted through the skin and into the stomach. But even when delivered into the stomach through a tube, food could still reflux up the esophagus and land in her lungs, causing choking or pneumonia.

Debra insisted that her mother would not want to be dependent on tubes, as it also clearly stated in her living will, a legal document Suzanne signed when she still had sufficient mental faculties. Having watched her mother’s quality of life ebb along with her mind, Suzanne’s daughter was clear and certain in supporting her mother’s desire to limit invasive medical interventions.

“She used to be the strongest person I knew,” Debra said, her voice cracking with memories of a person who, for her, had long since disappeared. “She always told us exactly what she wanted, and what she didn’t want.”

As Debra and I talked, the health aide feeding Suzanne was careful to allow enough time for each swallow. Suzanne had a tendency to store food inside her cheeks, which increased her risk of aspiration. Her appetite had improved as her fever resolved, but she still coughed occasionally while eating—each cough a reminder of her continued risk.

*

Coughing is one of the body’s crucial mechanisms for protecting against the complications of aspiration. As a propulsive method of cleaning out from the body unwanted junk that does not belong, coughing does for the lungs what sneezing does for the nose and what vomiting does for the gastrointestinal tract. A cough is a well-honed reflex already present in small infants, a preprogrammed response triggered by any foreign material touching the sensitive airways and lung passages.

Still, everybody will aspirate in their lifetime, and coughing is the body’s attempt to cope with aspiration’s inevitability. For healthy people, it works quite well—a coughing fit when food or drink goes down the wrong pipe handily flushes any trespassing material out of the lungs and generally eliminates the risk of developing pneumonia. Whatever remnant of aspirated material is still left in the airways is slowly brought up and out by a self-cleaning mechanism of the lungs called the “mucus elevator,” another example of the body’s need to compensate for the throat.

But an effective cough requires a certain strength that Suzanne simply did not have. Her frail attempts lacked the volume and reverberation of coughs robust enough to actually move mucus. Coughing relies on chest and abdominal muscles squeezing tightly while vocal cords in the larynx are sealed closed to block the outflow of air. This builds up pressure inside the chest. When the vocal cords suddenly pop open, the pressure releases and pushes out any foreign goo. But Suzanne could not muster the strength. All of her body’s defenses were overwhelmed and failing.

Still, everybody will aspirate in their lifetime, and coughing is the body’s attempt to cope with aspiration’s inevitability.

On Suzanne’s fourth day in the hospital, my pager squawked toward the end of rounds, a nurse asking me to come quickly. I arrived at her room to find Suzanne struggling to breathe, the muscles of her neck and chest straining to huff oxygen through the face mask the nurse had placed back over her face. She had aspirated during breakfast—an event I had been dreading but perpetually expecting. Her daughter stood at the bedside teary-eyed, stroking her mother’s thin veiny hand and wiry hair.

Beside Suzanne beeped a bedside monitor, and its flashing display showed a concerningly low oxygen level. Leaning Suzanne forward with the help of her nurse, I listened to her lungs—the gradual improvement in clarity over the previous days was erased, and her breathing once again sounded like bubbling gruel. With a plastic catheter, I suctioned remnants of breakfast from her throat to prevent further aspiration. The next step for a patient like Suzanne, with a low oxygen level despite breathing pure oxygen through a mask, would be intubation, a plastic tube snaking through her throat and into the trachea so that a ventilator could breathe for her.

Turning to Suzanne’s daughter, I hastily rehashed our previous discussion about breathing tubes: we could call the hospital’s intubation team and transfer her to the intensive care unit (ICU), or we could focus on her comfort and avoid such heroic measures.

“Mom would not want to be kept alive on a machine,” she stated firmly.

I ordered the nurse to give a medication to relieve the panic of suffocation, a measure of comfort that was within her well-defined goals of care. The nurse left the room and returned with the medication, a few milliliters of clear liquid inside a plastic syringe, and injected it through the IV in Suzanne’s arm. Within minutes, the look of fear in her eyes calmed—her agitated breathing pattern slowed slightly but persisted.

*

As a physician, I was trained to fight unceasingly against disease and death, to battle perpetually against the human body’s failings—including aspiration. But for certain patients, the time comes to shift priorities. Such decisions are difficult and always made privately between patients and their families, in consultation with their healthcare providers.

Bodily decline comes in different flavors, and the choice to accept or forgo medical interventions is different for every patient. For Suzanne, Alzheimer’s had left her with no mind to watch over her failing body, and she had decided years earlier that she would not want to live long with such a life. Other patients value extending life’s duration at all costs, especially when their mental faculties remain intact. For example, a close family friend was suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a devastating neurological condition in which a person’s muscle strength gradually and irreversibly degrades into total paralysis, but with no accompanying mental decline whatsoever. Unlike in Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, my family friend’s mind remained perfectly sharp as the body around it wasted away. When he began to aspirate constantly and could no longer eat through his mouth, he chose differently than Suzanne and had a feeding tube placed into his stomach.

Soon breathing became difficult because he couldn’t even muster the bare physical exertion of drawing air into his lungs—a sign of terminal weakness. He opted for a breathing tube permanently placed through a hole in the front of his neck. For this friend, such interventions would prolong his life but not slow his physical decline. But they offered value to him as long as the mind trapped in his failing body could still enjoy the presence of his grandchildren. In the last days of his life, he sat completely paralyzed in a wheelchair, but still could relish the feeling of being hugged and kissed by his adoring family.

When I worked as a hospitalist, conversations about a patient’s goals of medical care were an everyday part of my job. In many of my elderly and aspirating patients who could no longer communicate their wishes for or against aggressive therapies, legal documents often conflicted with a relative’s bedside opinion, or family members disagreed among themselves about the options. More than once I’ve seen an elderly patient’s adult child who had been estranged for years return to their parent’s deathbed with unrealistic hopes of recovery. Another adult child who had been at the parent’s side through years of decline, who had accompanied them to innumerable doctor’s office visits and through repetitive hospitalizations, often was the one who knew it was time to let go.

A dying patient frequently exposes unpleasant dynamics within families. I have often been in the middle of strained sibling relations degraded over decades that finally came to a head like an abscess under pressure bursting forth with thick, foul-smelling pus. Just as the human body and mind degrade with age, human relationships also begin to creak and fray over years. Personalities harden like arteries, and the bustle of life strips people of the energy to work through the inevitable accumulation of misunderstandings and slights. As the hospitalist—and a complete stranger—my job was usually to mediate and soothe, to ease familial tension just as I eased the pain and suffering of a human body as it exited life.

Besides the intake of food and air, the throat is also where exhaled air from our lungs is whipped into voice by the larynx. It is through our throats that we express ourselves and how strong-willed and independent people like Suzanne make their wishes known. As a physician, my job is to listen to patients, especially when they can no longer speak for themselves. People who fear being victimized in their last days by healthcare workers and the painful bodily invasions of medical care should sign living wills dictating which measures are off-limits. Research shows that when doctors themselves become patients at the end of life, they more readily wish to forgo aggressive therapies, probably because we often witness, and personally enact, the senseless brutality that comes at the expense of quality and comfort. Throughout life, each person speaks for themselves, but when our bodies and voices fail, we must rely on our families and friends, or documents like a living will, to speak for us.

Suzanne’s daughter was atypical in her keen understanding of her mother’s inevitable trajectory—and the fact that the living will reflected her feelings made my job easier. Caring for Suzanne was one of the most tension-free end-of-life experiences I had yet had with a patient, and it left an indelible mark on me as a young physician. Debra had been deeply involved in her mother’s care over the years, and she knew as surely as I did that death was coming soon no matter what we did.

Suzanne survived the initial aspiration event, but over the following two days, her temperature rose into fever once again and her oxygen level declined further, a sign that her throat’s bacteria had again breached her lungs and were burgeoning into another pneumonia. Her condition worsened despite powerful antibiotics.

Later that day, Suzanne pulled the oxygen mask off her face, as she had on admission, but this time we let her. In her throat, mucus accumulated and began to rattle with each breath, a sign that the last strands of her body’s defenses were unraveling. As Debra and Suzanne’s large extended family surrounded her hospital bed, her breathing gradually sped up, and then progressively slowed to a final halt.

As a medical student, I mocked the throat’s design, and as a young hospitalist, I viewed it as a significant threat to my patients.

During embryology, the human body’s design is forged microscopically in the womb. We each begin fetal life as a flat, microscopic disk of cells that, just a few weeks after conception, rolls itself, crepelike, into a tube. This roll creates the human body’s basic blueprint: a tube with an entrance at one end and an exit at the other. The body grows and embellishes itself from that starting point, its structural complexity soaring. But the original tubular configuration remains throughout life. As grown humans, we are little more than extravagantly decorated tubes with entrances for food, drink, and air at the front, and all our exits clustered at the other end.

This tubular construction is the origin of the throat’s design. As each human embryo develops, the body’s single common entrance at the front end splits into two respective tubes side by side—one for food and one for air—and the enduring peril of choking and aspiration is born. The body compensates by sprouting a face and brain to better regulate what is allowed through the entrance, and develops protective mechanisms like swallowing, coughing, and gagging, which work most of the time.

Beginning with the first breath after birth, air and food are precisely partitioned in our throats—a lifelong pharyngeal juggling act. Keeping food out of the airway is among our body’s most basic responsibilities, but when the throat of a person debilitated by strokes or Alzheimer’s can no longer sustain the coordination of juggling, aspiration is how the body gives out. It is among the most common causes of death in such patients.

As a medical student, I mocked the throat’s design, and as a young hospitalist, I viewed it as a significant threat to my patients. But after years of working as a physician, I came to also see it as the body’s way out of life. Aspiration pneumonia was once called “old man’s friend” because it often brings a dignified end to prolonged suffering in the elderly and ill. Like a cyanide pill kept in a locket, the throat’s precarious anatomy becomes a degraded body’s escape hatch. And sometimes, no matter how much we want the people we love to hold on for a little longer—such as when my wife’s grandfather with Parkinson’s disease was repeatedly admitted to the hospital with one pneumonia after another—the end cannot be forestalled any further. Sometimes the body decides for us.

Through caring for patients like Suzanne, I realized that there is wisdom in the throat’s design after all.

__________________________________

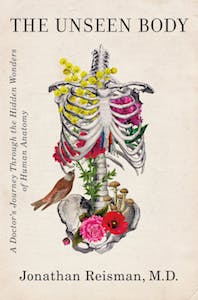

Excerpted from The Unseen Body: A Doctor’s Journey Through the Hidden Wonders of Human Anatomy. Used with the permission of the publisher, Flatiron Books. Copyright © 2021 by Jonathan Reisman, M.D.

Jonathan Reisman, M.D.

Jonathan Reisman, M.D., is an internist and pediatrician whose work has carried him from northern Alaska to the emergency rooms of rural Pennsylvania. An enthusiastic humanitarian, he volunteered at a high-altitude clinic in Nepal through the Himalayan Rescue Association in 2016. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Slate, and The Washington Post.