Unlocking Reason: How the Deaf Created Their Own System of Communication

Moshe Kasher Explores Deaf History, Language and Education as the Hearing Child of a Deaf Adult

I am a CODA, a child of a deaf adult, which, I guess, makes my mother a COHA, a child of a hearing adult. Two actually.

One was her father, Dick Worthen, a man’s man, a house builder, a World War II airplane mechanic, an English professor, a bastard. My entire life, I never heard my grandmother speak a single positive word about Dick until that day she told me he made her shudder with orgasmic bliss every single time they banged. Dick fell asleep at the switch on parenthood. Dick’s only child, my farting mother, Beatrice, was born deaf, her eardrum ballooned up into non-functionality. And Dick, a prominent English professor in the Bay Area, an activist for the advent of the modern community college system, and by all accounts a remarkable and passionate advocate for the importance of the mastery of language, never learned sign language.

Until the end of his life, his communication with his only child, my mother, was limited to a mix of cartoonish gesticulations and scribbled notes. The master of communication couldn’t communicate with his own child. Which is tragic, but also tragically common. The vast majority of deaf people are born to hearing parents, and a heartbreaking number of those parents never bother to learn the language that would enable them to have a relationship with their children.

My grandmother, Hope Worthen, receiver of Dick’s seemingly magical dick, was the “other way” this story can go. She was a public school teacher in the Oakland public school system. The moment she realized my mother was deaf, my grandmother quit her job, went to graduate school in deaf education, and eventually went back to work for Oakland public schools, leading their program teaching deaf children. In other words, she did what mothers do. She put her child first, and my mother reaped the benefits.

The decisions of people with zero experience in the deaf world, who have never really thought about deafness in any way, shape the future of the deaf.

This question is raised every time two unwitting hearing people give birth to an unexpectedly deaf child: “What are we going to do?” Their answer to that question decides not only their relationship with the child but also forges that child’s destiny, determines if they will be a professional or a pauper, illiterate or enlightened, independent or subordinate to state-sanctioned “help.” The decisions of people with zero experience in the deaf world, who have never really thought about deafness in any way, shape the future of the deaf, again and again.

Though Dick’s neglect is common, more common still are passionate parents who only want the best for their deaf children. But a parent’s love for their children is not a guarantee of sound decision-making. In many ways, it can have exactly the opposite effect. People’s love of their children is so overwhelming it can become impossible to recognize the choice you are making for that child is actually a gateway to their downfall.

This kind of destructive, “best interest” parenting is made more acute by faulty information. Sometimes this information comes from a QAnon adherent, convincing a parent that the polio vaccine is filled with the spinal cord fluid of enslaved unbaptized babies, and sometimes, in the case of the deaf, it comes from the inventor of the telephone.

*

Young Alexander Bell was born with a chip on his shoulder. Unlike his brothers, he had been born without a middle name, and he pleaded and petitioned his dad for the dignity afforded a three-named person. On his eleventh birthday, Daddy Bell relented and gave him the gift of the middle name Graham. This just goes to show you how poor and bored people were in the mid-1800s: You could delight a child with a birthday gift of being named after a cracker.

You know Alexander Graham Bell as the man who invented the phone. But to the deaf community, he is more than that, a self-appointed Moses, a boogeyman, a Pied Piper, playing a flute no one could nor wanted to hear, guiding the deaf to their educational doom.

Bell was, like me, the child of a deaf mother and was married to a deaf woman. You’d think that would ingratiate the deaf to him, that his connection with that world would be, as mine is, tender and loving and filled with a fierce loyalty. And maybe Bell felt that loyalty, but tender and loving he was not. It is not hyperbole to say that, in some ways, he wanted to eradicate the deaf from the face of the Earth.

Like most hearing people throughout the history of the deaf, the way he proposed to do it was to “help” them. Without even asking if they wanted that help, he would insert himself into their world, slam a railroad switch into the track of their emancipation, and force a crossroads where before there had been a straight line.

He was, for all intents and purposes, an imperialist, considering his superiority objective and decreeing the great tragedy it would be to deny it to a primitive culture. And, just like standard-issue imperialism, the savages he wanted to liberate were unaware of their savagery; they were whole and complete, not in need of rescue. The liberty he offered would quite quickly prove itself to be a prison.

Before Bell imposed his will upon the deaf, they had been on a one-hundred-year journey out of darkness. Their own self-initiated liberation was a dramatic tale of impossible odds, Napoleonic violence, Catholic education, and three singular geniuses living at the same time, in the same place: a tale that eventually led to the founding of the National Institute for Deaf Children of Paris.

Prior to the establishment of the school in 1750, the station of the deaf in France (and the rest of the world) was largely a dire one. We’re talking old-school “bath a month” France, so let’s be real: The station of everyone in France other than powdered-wig, paint-a-mole aristocrats was pretty dire.

But if you were born deaf? You were fucked.

Often, you’d be born poor in a village where you were the only deaf kid. The only language you’d ever receive or experience was whatever gesture you and your family invented in order to get you to understand when Papa said, “Pass the ratatouille.” You’d be born in the dark, destined to destitution, largely wordless and languageless, an island of deafness alone in a sea of the hearing.

But what if luck smiled on you and the genetic deafness in your family tree produced more than one deaf kid? At that, your chances of intellectual freedom exploded. You and your deaf sibling could pass language back and forth, building on it an increasingly complex structure.

With the simple power of one peer, a peer who defaulted to your natural state of communication, you could, quite literally, create a new language. A language of two. With that, you could unlock your mind, learn to communicate, and step out into the light.

A pair of siblings just like that met a Catholic priest, Charles-Michel, abbé de l’Epée, “the Abbe,” in 1770 and changed the destiny of the deaf in France and then the world.

Prior to this meeting, the intellectual status of the deaf was in question. Aristotle himself thought that the deaf were incapable of reason or complex thought. He claimed reason without hearing was an impossibility. The truth is, it is not hearing but language that unlocks reason, and deafness at that time had the profoundly destructive effect of cutting people off from language.

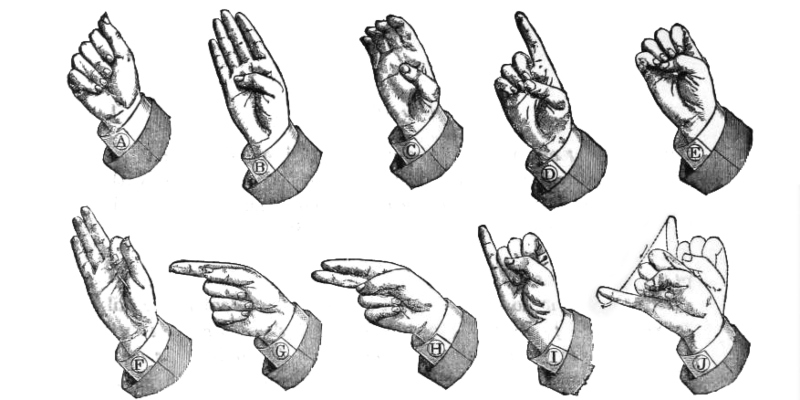

But like two male velociraptors in a Michael Crichton book, deaf people (like all people) “found a way.” They created language from nothing, and it was this language that the abbé encountered in a Parisian slum in 1770. Struck with the hand movements he saw exchanged between two deaf sisters, he knew that he was looking at language and, at that moment, he dedicated his life to finding a way to use those signs to educate the deaf, and to allow them salvation.

The truth is, it is not hearing but language that unlocks reason.

Salvation was most of his concern. The abbé intuitively saw that deaf people had no less ability to reason than anyone else but, if they didn’t have language, they could not be given the sacrament and were therefore damned to hell. This makes perfect sense of course: an almighty God, looking down at the deaf and saying to the devil, “Look, if they could talk I would grant them permission to eat my God-Body biscuits but, with things as they are, my hands are tied. They’re all yours! Into the eternal hellfire they go!”

From this religious instruction, and these two signing girls, the first free school for the deaf was formed, the National Institute for Deaf Children of Paris. The abbé began to gather deaf students from around France and to teach those children.

The abbé was a teacher, but he learned as much as he taught. As he was taught by his students how to sign, he reciprocated by using those very signs to teach them French, how to take the sacraments, and indeed how to acquire the knowledge that had been withheld from them behind an unscalable wall of spoken language.

In other words, the students taught him how to weave rope and the abbé taught them how to form it into a ladder that they could use to scale the wall. Over the years the signing system, aided and added to by all of the gathered deaf students there, formed and shaped by the collective body of the deaf in Paris and the teachers at the school, became increasingly complex and sophisticated, and by the time Laurent Clerc, the father of modern American Sign Language, arrived, fresh from a French village and hungry for language, there was language waiting for him.

Born in 1785 in a village outside of Lyon, France, Laurent Clerc became deaf after an accident when he was one year old. He was lucky enough to be the son of the mayor. If he’d been the son of the baker, odds are we’d have never heard of him and he’d have died in that same village, making baguettes in a languageless world.

I know that France is so charming that it’s hard to paint a tragic picture by saying “this poor guy might’ve been living in a rustic French village, pulling crusty bread out of an oven and spreading it with fresh-churned butter made from the milk of the cow that lived next door.” But for Clerc and the world, it would have been a tragedy, because when Clerc left that village for Paris and the school for the deaf, he began a journey toward changing America, changing the world, and changing my life.

__________________________________

From Subculture Vulture: A Memoir in Six Scenes by Moshe Kasher. Copyright © 2024. Available from Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Moshe Kasher

Moshe Kasher is a stand-up comedian, writer, and actor. He is the author of Kasher in the Rye. He has written for various TV shows and movies, including HBO’s Betty, Comedy Central’s roasts and Another Period, Zoolander 2, Wet Hot American Summer, and many more. His Netflix specials include Moshe Kasher: Live in Oakland and The Honeymoon Stand Up Special. He’s appeared in Curb Your Enthusiasm, Shameless, The Good Place, and other fun things. He co-hosts The Endless Honeymoon podcast with his wife, Natasha Leggero. Kasher lives in Los Angeles with Leggero and their daughter.