Uncovering the Forgotten: The Struggle For Trans History, From Nazi Germany to Today

Milo Todd on Writing Historical Fiction in an Era of Alternative Facts

Several years back, I started researching transgender existence in Germany before, during, and after Hitler’s stranglehold on the country. It was a painstaking project, if only because of how arduous it was to uncover that history when entire governments had tried so hard to destroy it. But it was important to me and so I kept at it.

What resulted was a work of historical fiction, The Lilac People, which narrates the stories of a few trans people (and a cis ally) under the thumb of fascism. The book eventually found a home with Counterpoint Press in January 2024. After acquisition, we did the usual thing: We planned, we waited, we hurried up and then waited some more. And all the while I kept an eye on the goings-on of the United States, the concerns of fascism in our own country, the book bans and erasures of history.

Then the election of November 2024 hit. I watched as the 47th president of the United States took office on January 20th, only ten days before Hitler became Germany’s chancellor 92 years prior. I counted down what I call the Hitler Clock—the first 53 days of Hitler’s new role as he actively tried to dismantle everything he could; as the president now seemed to be attempting to, quite genuinely, follow the Hitler playbook.

I watched as history attempted to repeat itself—as of this writing, continues to attempt to repeat itself—with trans people as one of the first in the crosshairs. Passports, name changes, gender markers, healthcare, bathrooms, public engagement of all sorts. Anything that removes personhood, existence, and the right to body. Because if you strip these away from the most vulnerable and find little resistance from others, you can then start to work up the ladder.

Attempting to uncover forgotten people and destroyed histories is a headache in itself, but in our growing age of lies, the work sometimes feels more like an existential crisis.

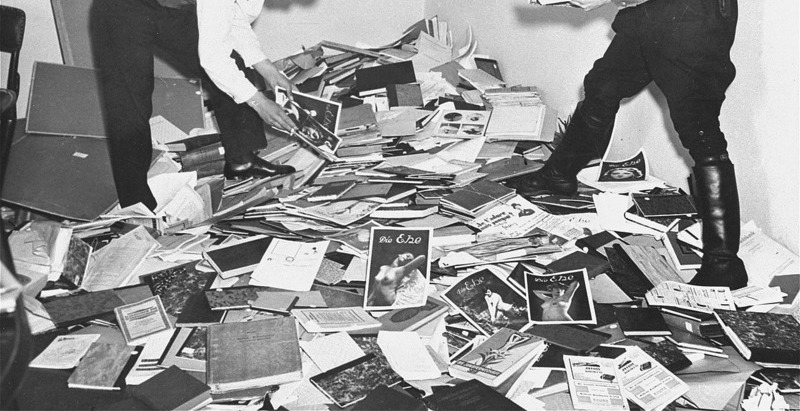

My book is set to debut on April 29th, exactly one week before the 92nd anniversary of the first (and worst) queer book ban in documented history: the burning of the archives at the Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin. That destruction was so impactful that it set trans rights, healthcare, and education back about 100 years. And now here we are, almost exactly 100 years later.

As someone who writes about and instructs on transgender history, I grapple with erasure, misrepresentation, and denial on a regular basis. Attempting to uncover forgotten people and destroyed histories is a headache in itself, but in our growing age of lies, the work sometimes feels more like an existential crisis.

I’ve spent years on a book about events that never happened while I myself don’t exist.

*

In 2024, a citizen committee in Montgomery County, Texas mandated that all public libraries move the nonfiction children’s book Colonization and the Wampanoag Story by Linda Coombs from “nonfiction” to “fiction.” Reflecting on this, Hannah H Kim wrote in “The truth about fiction”:

The power to label books as ‘fiction’ or ‘nonfiction’ is to demarcate what is real and what isn’t, what is true and what is false, what is imagined and what is actual….They didn’t care about the status of the contents of the book so much as they cared about the contents of what we take to be real and true. All that mattered to them was that it not be considered nonfiction—and if it’s not nonfiction, it must be fiction, right?

…What grounds the nonfiction/fiction distinction is not that the former is based on truth or facticity per se, but that the former contributes to how we see the world insofar as it organises the kinds of truths that we care enough about to read and write about. The Montgomery County Commission didn’t initiate a systematic audit of all nonfiction books that might include false or misleading information. Rather, they targeted a book whose claim to truth practically interfered with their understandings of themselves and the country.

These are intentional actions. In his essay, “Twenty Lessons On Tyranny,” (which is based on his book, On Tyranny), Timothy Snyder says: “To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights.”

Likewise, as Dan Williams succinctly says in, “On conspiracy theories of ignorance”: “When knowledge is easy to come by, manipulation is more challenging and less prevalent.”

In Nazi Germany, it was much easier to suppress information. But now in the age of the internet, it’s more difficult to sweep things under the rug. The next best thing? Say the information you can’t suppress is wrong. Or better yet, fake. For an individual to otherwise still believe such information marks them not just as someone who misunderstands, but as someone so unhinged that they’re now a danger to the country itself.

Image source: Griffin Hansbury, New York City, February 2025.

Image source: Griffin Hansbury, New York City, February 2025.

The mainstream’s concept of trans history, and trans people at large, plays a notable part in this approach. It creates a simple formula: A trans narrative is only true or untrue if a given reader deems it so. Trans existence becomes dependent on singular whims that swing drastically between extremes.

*

When I made acquaintances with someone at a party and, upon hearing that I wrote trans historical fiction, they excitedly pulled me by the wrist to their friend:

“This is Milo! He writes speculative fiction, too!”

*

When I pitched a piece of short fiction about a trans person trying to access healthcare during an illness:

“This isn’t a good fit for us, but we hope you feel better soon.”

When I double-checked that I had, indeed, submitted under the category of fiction, I thanked them for their reply, but politely explained that the story was fiction (if only to correct the record):

“It’s still not a good fit for us, but we hope you feel better soon.”

*

When my agent pitched my historical fiction about a gender nonconforming person relevant to 1600s piracy on the Atlantic Ocean:

“I don’t understand. Where’s the time travel?”

“This has bestseller potential, but the lack of magical realism is confusing.”

“Have you considered making it YA? Because I could sell it if it was YA.”

*

When my agent pitched my historical fiction about a trans person trying to survive 1960s NYC, this time complete with painstaking reference to the numerous people I’d interviewed and the meticulous research I’d done:

“I’m sorry, this story is wonderful, but I just don’t believe the world you’ve created.”

“An absolute stunner, but we don’t represent alternative reality books.”

“I’m pretty sure this isn’t true because I haven’t seen other books write about this.”

*

When my agent pitched The Lilac People:

“This author’s one to watch, but nobody will ever believe this happened.”

“Are you sure this is true? Because I know a lot about WWII and I’ve never heard about this before.”

“Absolutely groundbreaking, but I don’t think readers will get on board with this.”

*

A part of me can’t blame these folks. When you’re never taught trans history in school—and when the identity sometimes isn’t allowed to be recognized in the present, either—and the only trans history you come across in books is reimaginings, indirectly asking a person to grapple with everything they’ve ever known being a lie is a lot to ask in a single email. Despite the many trans novels that have published over the past handful of years, most of them have been limited to a select few categories. It creates an unfortunate assumption: If vast quantities of such stories are published, then a lack of historically accurate past must be the truth. While speculative and reimagined stories of trans people are important to have (and we should keep publishing them), the lack of publishing of authentic history has further distorted public perception of trans people in history. It creates a cycle that continuously upholds one’s own beliefs, subconsciously or otherwise.

*

In “The Production of Ignorance,” a chapter in Trans Like Me by CN Lester, they engage with the difference between active and passive lacks of knowledge:

[I]t is not just the absence of knowledge that keeps a truth from being widely known and accepted; it is also the active production of ignorance that suppresses that truth….[I]t is not that trans people are ignored entirely, but that what we are taught as fact can often obscure and distort the truth in a way that even silence could not.

In their essay, “A Future Without a Past” (originally found in June 2019 at the now-defunct Freeword.org.), Lester outlines this process in four steps: 1) blankness (a lack of trans history and/or teaching of trans history); 2) a testimony of destruction (evidence of the policing, arrest, murder, etc. of trans and/or gender nonconforming people themselves); 3) the destruction of meaning (evidence that trans history has been actively and deliberately erased, suppressed, and/or misrepresented to reduce the trans person illegible as trans); and 4) the glossing over of modern recoveries of said histories (usually seen when gender nonconforming behavior is automatically coded as “gay,” “lesbian,” or in the case of trans masculine behavior, “women’s liberation”) without acknowledging the fact of complexity.

A trans narrative is only true or untrue if a given reader deems it so. Trans existence becomes dependent on singular whims that swing drastically between extremes.

Within their analysis, Lester asks a salient question:

We call it gaslighting when one person manipulates another—manipulates the world around them—so as to deny agency, independence, and freedom.

What do we call it when the same process plays out on a society-wide scale?

*

I always assumed that the erasures and rewrites of history were something a person recognized after the fact. I didn’t realize it was something you could see happening in real time. The war in Ukraine is now Ukraine’s fault. The attempted coup on January 6th was a day of love. There were never any trans people at the Stonewall Uprising.

The surprise for me isn’t that such attempts at erasure are happening, but rather that they seem to be working on notable swaths of people. It immediately puts me in mind of Snyder’s No. 1 rule: “Do not obey in advance. Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these, individuals think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked. A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do.”

But in terms of trans history and existence, do modern people recognize that they are obeying? Are they actively choosing to do so? Or do people genuinely not know any better due to a lack of information, and therefore believe lies as truth? Or is it, more specifically, they’re embracing willful ignorance to keep their concept of reality at ease? “Readers won’t get on board with this,” one of the publishers told me. Nothing else about the book mattered. It was a question of shaking the cage of one’s reality, and concern about how delicate one’s psyche may be inside. Best not to chance it.

*

I’m no fool. The Lilac People has suddenly received notable attention since January, and that attention continues to grow as the United States continues to spiral. As grateful as I am for all the kindness and enthusiasm and support, I also know why the attention is happening. It’s not because my novel is a piece of fiction. It’s because it suddenly looks quite real.

__________________________________

The Lilac People by Milo Todd is available from Counterpoint Press.

Milo Todd

Milo Todd is co-EIC at Foglifter Journal, runs The Queer Writer newsletter, and teaches creative writing and history. He’s received awards, accolades, and fellowships from such places as Lambda Literary, Tin House, Pitch Wars, GrubStreet, Monson Arts, and the Massachusetts Cultural Council. His debut, The Lilac People, publishes through Counterpoint on 4/29/25.