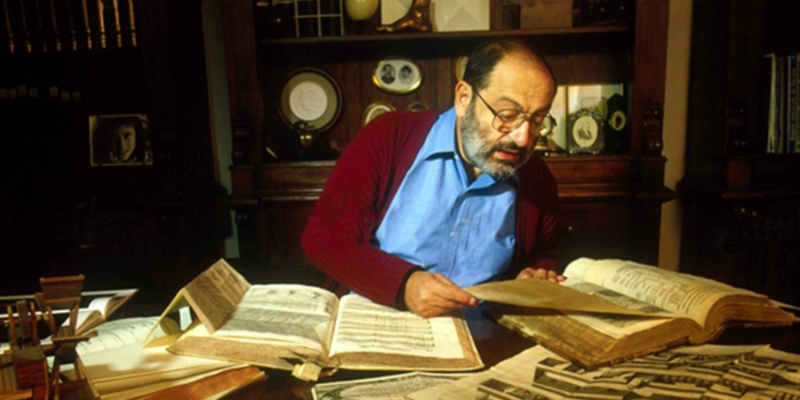

Umberto Eco’s Favorite Books Give New Meaning to the Phrase “Deep Cut”

Stefano Eco Shares Some of His Father’s Beloved Texts to Celebrate the Premiere of Umberto Eco: A Library of the World

For the American premiere of Umberto Eco: A Library of the World in New York, I have been asked to provide a short list of some of my father’s favorite books. Lists being one of his favorite subjects, he would have given a list of 100 titles—or none at all. But, as with the titles that I am listing, he would have chosen some obvious and some obscure ones—as in “there is no way to find a modern copy of that.” Such are the pleasures of bibliophiles.

–Stefano Eco

_______________________________

Join Lit Hub at Film Forum on Friday, June 30, at 6:20 p.m., where we’ll be co-presenting a screening of Umberto Eco: A Library of the World, followed by a Q&A with filmmaker Davide Ferrario. Get up to two discounted $11 tickets (regular $15) by entering promo code LITHUB at checkout.

_______________________________

*

Francesco Colonna, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499)

The story of the book takes place in 1467 and consists of precious and elaborate descriptions of scenes, the protagonist of which is Poliphilo (“lover of many things,” from the Greek polú, “much,” + philos, “friend, lover”), who wanders through a kind of dreamscape in search of his beloved, all typeset in an unsurpassed design, the Holy Grail of printed book collectors.

Eco loved this book, considered one of the most beautiful in the world, because of the combination of text and image (in which the images dictate the narrative rhythm, as in the emblemata), because of the invented language that is deliberately the result of different combinations. The text of the book is written in a mixture of Italian and Latin, full of words coined from Greek and Latin roots, as well as Hebrew and Arabic terms found in the illustrations. The book also contains some Egyptian hieroglyphics, naturally with symbolic and esoteric meaning, perfectly suited to Eco’s biblioteca.

A little bibliophile’s quirk: Eco always recalled that within a few blocks of houses, in Milan, there were as many as four copies of Polifilo, including his own and that of the publisher Calasso.

*

Robert Fludd, Utriusque Cosmi Historia (1617)

If one types Fludd into Wikipedia, the first definitions that appear are these: “He was a British physician, alchemist and astrologer, an expert in theosophy.” He was a hermetic philosopher who belonged fully to the Hermetic-Cabalistic tradition of the Renaissance developed by Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, and Paracelsus. Fludd’s books could not be missing from Umberto Eco’s Bibliotheca Semiologica, Curiosa, Lunatica, Magica et Pneumatica. According to De Quincey, Fludd was the true (supposedly) founder of the Rosicrucians; with his truly false theories, Fludd largely inspired Eco’s most important works, starting with Foucault’s Pendulum. An important part of Umberto Eco’s library was devoted to books stating false facts or theories.

*

Heinrich Khunrath, Amphitheater of Eternal Wisdom (1605)

Heinrich Khunrath is one of the esoteric authors whom Eco loved most, to whom he dedicated the bibliophile’s booklet The Strange Case of the Hanau 1609 in honor of the highly sought-after edition printed that year. An adept of spiritual alchemy, like Paracelsus, Khunrath (1560-1605), a physician, condemned for heresy by the Sorbonne theologians, was convinced that the road to knowledge passed through a long and complex initiation, mediated by divine help and the rediscovery of the philosopher’s stone.

Believed by Frances Yates to be the linchpin between John Dee’s philosophy and Rosicrucian doctrines, in 1597 Khunrath published the beautiful “Vom hylealischen, das ist, Pri-Materialischen Catholischen, oder Algemejnem Naturlichen Chaos.” A book full of valuable pictures and engravings that Eco was proud to have wrestled from his rival, the great Dutch collector Joost Ritman.

*

The works of Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680)

Of Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit, Eco boasted that in his library of rare books he possessed all but one book. Kircher was the encyclopedic author of more than 40 works, in which he dealt with optics, volcanoes, earthquakes, music, celestial spheres, the center of the earth, hieroglyphs and the customs of the Chinese, the Babelic alphabets and their tower, and the origin of language. And still he wrote about physics, mathematics, combinatorial logic and factorial calculus, distant lands, and made plans with Bernini. He never moved from Rome and the Roman College but made his Wunderkammer the most beautiful museum of any known then.

Was he right about everything he wrote? Not at all, quite the contrary. But Eco was attracted to this “universal man” precisely because of the beauty of the outlandish conjectures with which he “furnished” the pages of his in folio—whether true or false.

*

Joris-Karl Huysmans, À rebours (1884) and Là-bas (1891), and the works of Alexandre Dumas (1870-1891)

Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum revolves around a group of employees of a small publishing house who playfully concoct a World Plan, involving Knights Templars and Rosicrucians, the Kabbalah and the Holy Grail, only to discover that several obscure forces have taken it seriously. In Eco’s The Prague Cemetery, the idea of a worldwide plot is placed into a great 19th-century feuilleton. Favorite literary precedents? À rebours (1884) and Là-bas (1891) by Joris-Karl Huysmans, books loved by Eco, as well as the great books of Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870), from The Three Musketeers to Twenty Years Later: cloak and dagger, failed writers, Satanism and false anti-Semitic protocols creating real historical tragedies.

*

James Joyce, Ulysses (1922)

James Joyce was the modern author that influenced Umberto Eco the most. He has devoted two books and various essays to Joyce, named his son Stefano (“Stephen Hero”), and owned rare editions of Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. As a literary critic and theoretician in postwar Europe, Eco was one of the enthusiasts of Joyce’s modernity before most academicians.