Tyriek White on Juxtaposing Brooklyn's History With Lived Experience

In Conversation with Maris Kreizman on The Maris Review Podcast

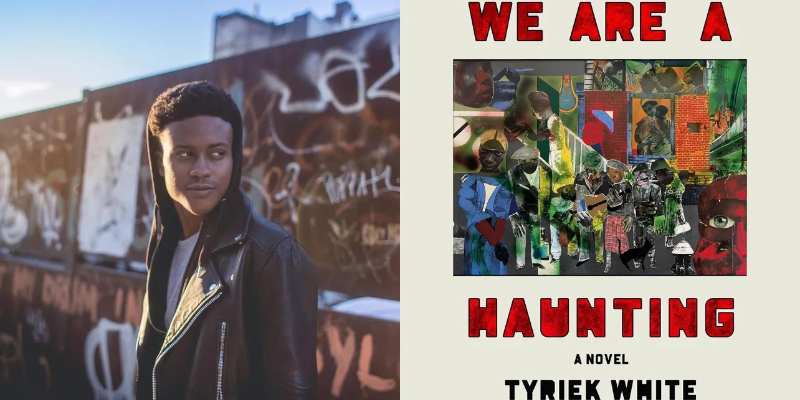

This week on The Maris Review, Tyriek White joins Maris Kreizman to talk about his novel We Are a Haunting, out now from Astra House.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

from the episode:

Maris Kreizman: Let’s talk about how time works in the world of We Are a Haunting.

Tyriek White: For sure. I guess it kind of rejects Western ideology or views of time that just kind of move forward. I think sometimes in our experiences, especially growing up as children, time slows down, time oscillates, time kind of seems to revolve or seems cyclical at some points.

I think the book tries to lead you through a beginning, middle, end sort of situation, but it does question, especially being in New York, [how time works] in these fragmented places. Like, it’s easy for Colly, who’s the main character, to be walking down the street and be sucked into this sweeping memory that may take you out of this forward, beginning-middle-end kind of movement, but I think the book isn’t really interested in time. It’s more of a vibe. It’s more interested in the vibe of this world and these people.

MK: So much of the book is devoted to the history of New York City, and especially East New York, where the book is set. Tell me about creating that world, your research.

TW: Yeah. I definitely did a lot of research, especially into the history. Just simple kinds of things, like certain landmarks, the makeup of Brooklyn around the 18th century, and then really kind of overlaying that with the present, the New York and the Brooklyn that I knew, and seeing what juxtapositions come out, or what similarities bind these places together.

And you think about state occupation or occupation in general. You think of Brooklyn during slavery or the 18th century, it’s mainly the town of New Lots, the town of Flatbush, all these places. These streets are farmers and plots of land. And that’s largely where we get a lot of the street names from. And then that kind of occupation overlaid with state occupation. So, like, the neighborhood I grew up in, the community I grew up in, being occupied by police and the tension there.

A lot of it is my lived, embodied experience in New York. Just living, breathing, growing up, going out, getting into fights, the intangible kind of feeling of growing up in New York versus this meditated research I did. News articles, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle articles from like the 1800s. So I was just trying to do a balance of research and lived experience.

MK: A main point of studying the geography, of course, is that New York City is a very rich city. And poor people get shoved to the outskirts.

TW: Right?

MK: You don’t let NYCHA off the hook very easily and I appreciate that. Could you talk about that a little bit?

TW: Yeah, for sure. I try to humanize the people because they get inundated with requests all the time. So I try to capture the sort of humanness of it. At the same time, NYCHA is a state and federal organization that has honestly sold half of its rights. So, like, my neighborhood isn’t even truly owned by NYCHA anymore. It’s been sold to a private realty group. And currently they’re doing these renovations and adding LED lights and all these cool things, in theory. But it’s a little questionable now because I’ve been there since the book came out and I think the construction has put it in this place of… I end the book with this flood and this surreal kind of moment where it’s this breakdown and destruction of this place.

And then you go back and it’s literally like that now, due to construction and renovations. And that’s interesting. Like my experience growing up in New York, growing up in public housing has always been these institutions that kind of hang over your head: the police, housing offices, and other places, NYCHA. These kinds of institutions are run and governed by working class, middle class people – most cops are middle class – but that conflict comes into play when you’re just growing up in this neighborhood and there’s certain limitations, there’s certain things you want to get repaired. Lead in the ceiling that you want to remove. There’s this joke in the book of how it’s taking like ten years for housing to complete a work order. Which is a bit of an exaggeration, but it can feel like that sometimes.

MK: In the very beginning of the book, Audrey, Colly’s grandmother, says, normal people did not have to transcend their surroundings.

TW: Right, not an obstacle that needs to be overcome. We shouldn’t have to transcend or break barriers. We should just be able to live and thrive and survive, right? That’s the hope.

*

Recommended Reading:

__________________________________

Tyriek Rashawn White is a writer, musician, and educator from Brooklyn, where he served at-risk and marginalized youth, artists, and scholars in the classroom. He is currently the media director of Lampblack Lit. He holds a degree in creative writing and Africana studies from Pitzer College, and earned an MFA from the University of Mississippi. We Are a Haunting is his first book, and it just won the Center For Fiction First Novel Prize.

The Maris Review

A casual yet intimate weekly conversation with some of the most masterful writers of today, The Maris Review delves deep into a guest’s most recent work and highlights the works of other authors they love.