Two Vietnams: Chronicling a Father and Daughter’s Shared Love For the Same Country

Christina Vo on Writing an Intergenerational Tale of a Divided Land

I frequently refer to my father as “the man who doesn’t speak.” Once, a good friend questioned this description, asking, “How can your father not really speak to you?” It’s difficult to comprehend how someone might not converse with their parents, but few words ever passed between my father and I. For most of my life, silence was his most distinguishing feature.

After my mother died when I was a teenager, days would pass without seeing my father, a busy surgeon, at home. Sometimes, I heard his footsteps and the creaking of our hardwood floor, but our house was large enough so that we could merely be passing ships in the night.

By the time I returned from school, he would be upstairs in his bedroom, immersed in a book or watching TV. Dinner, often a simple meal like fried noodles and a hot dog or Chinese take-out, would be waiting for me on the kitchen stove, marking yet another day without interaction.

I realized that, like the divided nation he described, my father and I held two very different views of Vietnam.

Before I left for college, my father wrote and published a memoir titled The Pink Lotus. I read only fragments of the book, little pieces that he had never bothered to tell me that helped piece together the stories of his life. I knew he was a doctor in the South Vietnamese Army stationed on Phu Quoc Island when Saigon fell to the communists in 1975. Because of Phu Quoc’s strategic location, there were boats lined up prepared to evacuate Vietnamese refugees, so he fled Vietnam.

I read that my mother and their young son were left in Saigon. After spending time in refugee camps in Guam and Pennsylvania, my father secured sponsorship from a small New England hospital to pursue medical recertification. With limited English proficiency, he underwent retraining to continue practicing as a physician. My mother joined him in the US in 1976, a year after their first son passed away due to complications from hemorrhagic fever. I read enough to know his basic storyline, but there was so much more about my father that I failed to grasp.

*

After college I began an internship at the United Nations Development Programme in Hanoi. My father remained silent about my decision to go there, but I sensed his disappointment. How could I choose to return to the country he had risked everything to escape? Why would I venture to Hanoi after all he went through? I felt that my choice to live in Hanoi was perceived by him as a form of betrayal, even though nearly three decades had passed since the end of the war.

As a twenty-something living in Vietnam, I experienced a vibrant and dynamic life. I learned of my identity as a Viet Kieu—an overseas Vietnamese. While living in Vietnam, my father remained a constant presence in my thoughts, despite our minimal communication. I began to contemplate the concept of the motherland, the land of our ancestors, and think more about the hardships my father had endured to rebuild his life.

*

Over twenty years have passed since I first returned to Vietnam. While the distance between my father and I has remained, the divide is smaller. I visit his home in Virginia once or twice a year, and pay more attention to the ways he does show his love—through food, for example—than his silence.

Two years ago, after I relocated to Santa Fe during the pandemic, my father invited me to accompany him to a conference at Texas Tech University, where he was scheduled to present. He never clarified the reason behind his invitation. I thought it was because of the proximity of New Mexico to Texas, or perhaps he simply didn’t want to attend alone.

Because my father never asks anything from me, I immediately said yes. Before that, I had heard him speak publicly only a handful of times: at my mother’s funeral, my grandmother’s funeral, and at a reunion for his medical school class. On each occasion, the man speaking appeared to be a different person than the father I knew. He was deeply emotional, articulate, and moving.

Nervous as my father approached the podium, I watched as he delivered a captivating presentation on “Two Vietnams.” The entire room was engaged as he passionately discussed Vietnamese history and his belief that the country, born from division, remains divided today.

Afterward, the keynote speaker, former Ambassador John Negroponte, who was a member of the US Delegation to the Paris Peace Talks on Vietnam, shook my father’s hand and asked, “You’re a medical doctor. How do you know so much about Vietnam’s history?” To which my father responded, “Vietnam is a country that has always been at war with itself. I had to understand why the Vietnamese are always fighting each other.”

Returning home, the essence of his presentation resonated with me. I realized that, like the divided nation he described, my father and I held two very different views of Vietnam. If I was ever going to write about Vietnam, I would need to weave my father’s narrative with my own, creating a mosaic of memories of a nation he escaped and the nation that had lured me back.

As our stories intertwined, I drew parallels between our lives and our search for home and inner peace.

I sifted through his memoir, which was no longer in circulation. He didn’t retain the original files, so I transcribed the chapters that I planned to incorporate into our collaborative work. Chapter by chapter, alternating between our perspectives, I sought to discern our unique yet contrasting voices—his personal stories deepened with historical context, often masking profound emotions. Mine, embodying the spirit of a youthful adventurer, eager for new experiences.

*

When I delved into my father’s stories of Vietnam, I began to understand the fabric of his life and the essence of the reserved yet profoundly introspective man he is. He recounted a formative episode from his youth when he was sent to stay with his grandmother in Vung Tau, a southern coastal town, for several years. He never understood why, among his five brothers, he was chosen for this separation. His grandmother owned a longan orchard, which included a quaint townhouse available for vacation rentals, primarily attracting visitors from Saigon.

During his stay, he formed a deep connection with a woman who took him to the beach and gifted him toys. After her departure, he was left with a profound sense of longing for his mother and immediate family. This singular memory offered a glimpse into my father’s evolution—from a young boy in Vung Tau to a figure of remarkable independence, self-sufficiency, and, at times, detachment from his family. I saw a lot of myself in his story, as we both shared the absence of a mother figure.

As our stories intertwined, I drew parallels between our lives and our search for home and inner peace—him starting anew in the US, my return to Vietnam. I recognized the similarities in our struggles—him being Vietnamese in America, and me being Vietnamese American in Vietnam. We both experienced a certain nostalgia for the motherland. Vietnam continued to shift and change during my twenties, and if I longed for the country I had first encountered, I acknowledged the even deeper nostalgia my father must carry after nearly fifty years since the war’s end.

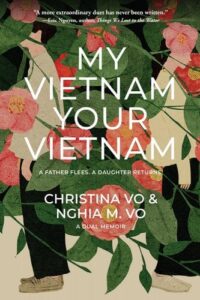

We each held our unique ideas of Vietnam—My Vietnam, Your Vietnam became the book’s title. Despite our differences and the few words exchanged between us, we shared a love for a country, albeit a love of a different iteration of Vietnam, and a desire to share our perspectives through writing.

Approaching fifty years since the war’s end, the concept of reconciliation repeatedly comes up. Although he may never see it this way, I believe that my return to Vietnam, which he refuses to do, was a way to reconcile that relationship for him, as an example of how intergenerational healing works. Through our shared love for a country we each experienced differently—my Vietnam, his Vietnam—we found common ground and a connection that surpassed the boundaries of language and silence.

__________________________________

My Vietnam, Your Vietnam by Christina Vo and Nghia M. Vo is available from Three Rooms Press.

Christina Vo

In her writing, author Christina Vo explores the interplay of culture, identity, and personal history. Her work reflects her commitment to understanding and sharing the complexities of the human experience. She is the author of The Veil Between Two Worlds: A Memoir of Silence, Loss, and Finding Home (She Writes Press). Her second book, My Vietnam, Your Vietnam (Three Rooms Press), is an intergenerational memoir co-written with her father, Nghia M. Vo. She has worked internationally for UNICEF in Vietnam, the World Economic Forum in Switzerland and served as a consultant for nonprofits in the US and globally. Christina holds an MSc in social and public communication from the London School of Economics. She lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.