Two Households, Both Alike in Indignity: An Interview with Anne Ursu

Gavin J. Grant and Anne Ursu on Chronic Illness, Writing, and Family

(I wrote this lying down. I sat at my old desk to write and it was a mistake so I had to lie down. Every time I rewrote this or sent Anne questions I was lying down. I dictated some of my questions. I even dictated some of the edits.)

My wife, the writer Kelly Link, and I had opened a bookshop in the next town over in October 2019. When the pandemic started we pivoted to curbside pickup, local delivery and shipping, and online events. It was a grind but our landlord cut our rent in half for a couple of months and all the part-time booksellers kept it going with us, taking turns to be in the store.

Despite being up-to-date with vaccinations and always wearing a mask, I came down with Long Covid in December 2021. I’d read so much about Covid that between wanting to avoid it myself and wanting to make sure our kid, who was born at 24 weeks back in 2009, would be safe I was really careful.

Long Covid diminished me so much I had to put our twenty-year-old small press on hold and step away from the indie DRM-free ebookstore I ran with a friend. I tried to go into the bookshop every week but at first even half an hour would leave me worn out for the next couple of days.

In August 2024 our 15-year-old, Jade, went to a local four-week summer camp. They wore a mask, ate outside, and used a daily nasal spray. On the last day their counselor called me: Jade had tested positive for Covid. (No one knows if there a genetic component to Long Covid but no other members of my extended family have come down with it.) In November it became obvious Jade was suffering from Long Covid. As I write, they are near bedbound.

Back in January of this year, Kelly posted on Bluesky that she now lived with two people with Long Covid and Anne Ursu reached out to pass along potentially useful pediatric Long Covid information as her teenage son, Dash, had been suffering from it.

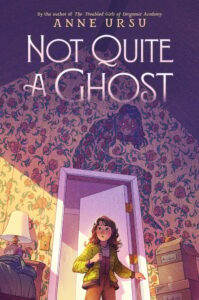

I knew Anne’s name and books and when I looked up her latest middle grade novel, Not Quite a Ghost, and saw that it was about an eleven-year-old, Violet, who comes down with a post-viral illness and there was a ghost inspired by Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s story “The Yellow Wallpaper” I knew it was for me. As I read the novel and thought about the parallels between Anne’s family and ours, I realized I’d like to interview her. The interview took place over a couple of weeks of emails as I very slowly put questions to Anne and she rapidly answered them.

*

Gavin: You have experience with CFS. Can you tell us about that and how it informed the book?

Anne: When I was a senior in high school, I came down with a very strange illness. I was so lightheaded that I often couldn’t stand up, and I was completely wrecked from exhaustion. I can’t even remember what the doctor said, except that he didn’t have any answers. It went away after about three weeks, but in college it would reappear here and there, and then pass again. And then junior year I started having issues with my brain; I couldn’t follow lectures anymore, and I couldn’t take notes. I got an ADHD diagnosis, but the psychiatrist said that she didn’t think that’s really what I had. Meanwhile, I was just losing energy and having all of these other strange symptoms, until I basically collapsed. I often couldn’t walk without a cane, and I couldn’t keep track of my own thoughts. That’s when I got a CFS diagnosis–as well as one of orthostatic intolerance, which explained the lightheadedness issues. I gradually got better, but over the next couple of decades kept having these crashes that would last for months, in addition to the orthostatic issues that could be really disabling.

And its impossible to get any help; so many doctors think CFS patients are either malingering or being hysterical, the prevailing treatment at the time was actively harmful, and the rare doctor that believes what you have is real still has no idea what to do. It’s thirty years since I first got diagnosed, and we don’t know much more about CFS than we did back then. Long COVID research has helped, but if people had bothered trying to figure out CFS at any point, maybe we’d know how to deal with Long COVID.

Gavin: Violet’s illness is purposefully unspecified but will be recognizable to anyone familiar with Long Covid, ME/CFS, and other post viral conditions. What are some of the things you wanted to include about these illnesses?

Anne: This was a challenging aspect of the book for me. Because she’s at the beginning of her illness, she just wouldn’t be getting a diagnosis. And—as I’ve been told by many a doctor—Violet’s symptoms seem quite “vague.” One of the curses of this illness is that there are simply no adequate words to describe what’s happening, and so we’re left with inadequate words that diminish the severity of the experience; everyone has fatigue, right? So I tried very hard to show how these symptoms feel though honestly writing those parts were very difficult. I didn’t want to put myself in those feelings again, and I’d honestly blocked a lot of it out.

Also, you truly cannot separate the personal experience of having this disease from the social experience of it. ME/CFS and other postviral illnesses simply don’t fit into societal narratives about how sickness works, and people get real uncomfortable when something doesn’t fit into their narratives. Illnesses have definable symptoms and physical signs, they can be tested for and treated (or at least managed). The idea that you could just become completely disabled out of the blue with something no one understands or can treat is a truth unpleasant for people to grapple with. And for many in the medical profession, it’s easier to blame the patient than recognize there might be things beyond their knowledge and abilities. For the patient, this means dismissal and denial. For Violet and her mother, they expect to get medical help—that’s what doctors are supposed to do, right? Help?—but instead Violet is treated as if she’s malingering or having psychiatric issues. I would guess most CFS patients have had this experience. And many have never found anyone who even acknowledges their disease is real.

Gavin: Our 16-year-old came down with Long Covid last October and now they are a shade of their former self. Their primary doctor has been great and we’ve taken them to Children’s but the main thing right now seems to be to get them to rest, eat, and sleep and do as little as possible—which is quite hard although they are getting used to it.

Your teenage son, Dash, has gone through something similar. Was it diagnosed? Did his experience mirror yours? Do you think the average doctor is better informed on post-viral conditions now than a generation ago?

Anne: My son got COVID in August, and just did not recover. After the first week or so, we expected him to start feeling less tired, but he never did. Then, other symptoms started appearing—brain fog, lightheadedness, headaches. We were very very lucky that his pediatrician was really well-informed about Long COVID, and that we were able to get him into someone at Mayo Clinic. But even with great medical support; it’s so hard. The Long COVID treatments that some doctors are trying haven’t been tested on pediatric patients. Through some combination of a booster, treatment for orthostatic hypotension, and sheer luck he was able to recover enough to go back to school for part of the day, but he’s still not back to normal.

I’ve heard enough stories from Long COVID patients to know how lucky we are that his doctors were so informed. People still report encountering disbelief and dismissal. My guess is that the above average doctor is a lot better informed on post-viral conditions. That said, the fact that ME/CFS often is a postviral condition isn’t widely known or accepted. I have to say that little has improved in the three decades since I first got sick. There haven’t been any major advances in understanding or treatment, it’s the same handful of doctors actually trying to treat the disease, and patients are encountering the same ignorance, skepticism, and hostility. The best most patients can hope for is finding a doctor who simply believes they are ill. It’s a disgrace.

Gavin: What drew you to this story? How did all the separate parts—chronic illness, moving house, losing friends, not to mention a ghost—come together?

Anne: I’d always wanted to write about this experience, knowing these kinds of illnesses affect kids, too. But I couldn’t figure out how; I write fantasy, and fantasy stories generally require their protagonists to be able to do things. It wasn’t until I started thinking more about horror as a genre that I found my way in; horror is about strange and mysterious things happening to you out of the blue that you have no control over.

I went looking for the right monster for the story and ran across an old article about classic horror books, and it listed Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper, a story about a woman who has some kind of postpartum mental health issue and is confined to the attic bedroom of a house by her doctor husband. She’s not allowed do anything, even read, so she spends her days looking at the horrific wallpaper in her room, and eventually she starts thinking there’s a woman trapped inside. It was the perfect story to get inspiration from—though Gilman’s character hallucinates the women in the wall, I wanted to write a real ghost. A ghost story, too, works very well for a character who is stuck in a room. And on a thematic level, if you’re haunted by a ghost, no one will believe you, an experience all-too-familiar for those with postviral illnesses.

I wanted Violet to have a lot going on in her life, because all the doctors would immediately think that this was a psychological response to the upheaval. But of course, people can have a lot of upheaval in their lives, and also be sick! The story required a move into a new house, but starting sixth grade and shifting friendships felt like very real things Violet could be dealing with when she falls ill. And that’s the thing about postviral illness; you’re just out living your ordinary-person life, and then the illness hits you and that whole life gets taken away.

Gavin: Violet has to go through so much grief from the everyday loss of leaving the house she grew up in to losing her childhood friends and then grieving the loss of her physical and mental faculties. What kinds of support did you see a patient like her receiving?

Anne: You know, I think grief is something that’s inherent to childhood. Everything is always changing and shifting, and it’s all so confusing, and we just expect kids to go along with it and be okay. Violet is lucky to have a lot of positive relationships in her life, from family to growing friendships, but in the end she also demonstrates the sort of resilience that comes from being a kid in the world and trying to figure everything out, day by day.

Of course, she also gets a cat!

_____________________________

Anne Ursu is the author of acclaimed novels Not Quite a Ghost, The Troubled Girls of Dragomir Academy, The Lost Girl, Breadcrumbs, and The Real Boy, among others. Her work has been selected as a National Book Award nominee, a Kirkus Prize finalist, and as a best book of the year by Parents Magazine, NPR, Bookshop.org, and Publishers Weekly. She lives in Minneapolis with her family and an unruly herd of cats.

Gavin J. Grant

Gavin J. Grant works from home with Long Covid. He is the publisher of Small Beer Press. Since 1996 he has (with Kelly Link) edited and published Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, a twice-yearly small press zine. Grant and Link have edited eight anthologies together. Originally from Scotland, Grant immigrated to the USA in 1991 and has worked in bookshops in Los Angeles, Boston, Easthampton, and for the American Booksellers Association. He has written for the Los Angeles Times, Christian Science Monitor, Xerography Debt, and Strange Horizons, among others. He lives with his family in Northampton, MA.