Two By Two: A Reading List of Books That Belong Together

Ian Williams on Authors that Make Good Literary Neighbors

These pairs of writers make good, neighborly companions on a bookshelf. They resemble each other in terms of style, subject matter, approach, or artistic values. I imagine them as living on either side of a semi-detached house: each household retains its distinctiveness although they may share a roof, a driveway, and a mail carrier. Yet sometimes the resemblances are so strong that you wonder if they’re not just neighbors, but relatives.

Ottessa Moshfegh, My Year of Rest and Relaxation (Penguin Books)

Anakana Schofield, Bina (NYRB)

Moshfegh and Schofield’s books can make you feel like you’re going crazy. They are the neighbors with the lawnless, overgrown garden, windchimes, and rocking chair on the porch. Being in the heads of their first-person narrators produces a pressured tightness akin to claustrophobia or a literary panic attack. Moshfegh and Schofield are merciless with their characters and readers. No exit. They grip your hand rather than hold it. They don’t share a voice (they’re inimitable) so much as a commitment to a vision. Their books are intent on setting and sticking to specific artistic terms to the death.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me (One World)

David Chariandy, I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You (Bloomsbury)

Here are two slim, readable, giftable books on race. Coates’s Between the World and Me is an American father’s address to his son. Chariandy’s I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You is a Canadian father’s address to his daughter. The books are sincere parental legacy projects (not vanity projects, mind you) that perhaps started off simply as parental anxiety. What warning can I give my child about the world they will inherit? And, of course, the books are intended for us. They started conversations or stood in for conversations that were too difficult to have with our own words. Both writers show Black fathers as tender, caring, protective, and emotionally sophisticated.

Joyce Carol Oates, Hazards of Time Travel (Ecco)

Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale (Anchor Books)

Dystopias. Totalitarian regimes. Discipline and punishment of free-thinking female protagonists. Check, check, and check. Oates and Atwood are the busy neighbors with immaculate home maintenance who make everyone else on the block look like slackers. They are among the most prolific and hardworking writers in the biz. They operate on a loop of unquenchable curiosity about the world and inexhaustible activity. Name a genre and they’ve written in it. Put forward an issue and they have thoughts on it. I can’t help but admire the breadth of their ambition and the ease with which they move between literary and popular modes. No affected literary preciousness with them. They embrace the real world, politics, social media—all the mess.

Ocean Vuong, Night Sky with Exit Wounds (Copper Canyon Press)

Billy-Ray Belcourt, This Wound is a World (University of Minnesota Press)

Roughly five years ago, these two writers burst on the scene with startling, highly acclaimed debut poetry collections. They are prodigies, but not the turn-of-the-century kind of prodigy that dashed off glitzy sentences. Instead, they are socially and politically conscious, with an unusual maturity, insight, and courage, especially when confronting generational and personal trauma. Neither Vuong nor Belcourt is afraid of beauty or love or the heady abstractions that previous generations of poets were warned against. Their writing is at once sharp with theory and supple with lyricism. They do not apologize for either.

Lydia Davis, Can’t and Won’t (Picador)

Miriam Toews, Fight Night (Bloomsbury)

Davis’s careful, correct sentences offer a tutorial in syntax, in respect for the language, in suspense and releasing information. Toews is similarly impressive at the paragraph level: she can overlay the past on the present, make you laugh and cry, drop you off miles from where you started. Although I doubt that either writer would identify as poets, they deploy poetic compression—not quite minimalism, but efficiency. Davis and Toews also blur life and fiction. For Toews, the autofiction is recognizable as plot; in Davis’s case, I suspect her chosen narrators echo some part of her interiority that is intricate, equivocal, and self-conscious. Both women share a quiet, unmistakeable intelligence that comes out in their humor. They’re the neighbors with the curtains drawn but you can still hear someone practicing piano on the inside.

__________________________________

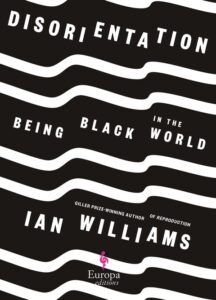

Disorientation by Ian Williams is available via Europa Editions.

Ian Williams

Ian Williams' debut novel Reproduction won the 2019 Scotiabank Giller Prize and his debut nonfiction work, Disorientation, was a finalist for the Hilary Weston Writers' Trust Award. His poetry collection, Personals, was shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize and his new collection, Word Problems, won the Raymond Souster Award. His short story collection, Not Anyone’s Anything, won the Danuta Gleed Literary Award and his first book, You Know Who You Are, was a finalist for the ReLit Poetry Prize. He is a trustee for the Griffin Poetry Prize and was recently inducted into the City of Brampton Arts Walk of Fame. A tenured professor of English at the University of Toronto, Williams will be the Visiting Fellow at the American Library in Paris in 2022.