Twenty Strangers on a Boat in the Dark: Javier Zamora on His Childhood Migration

From His New Memoir Solito

The following is an excerpt from Javier Zamora’s Solito, the author’s account of his migration from El Salvador to the United States when he was nine years old. In this section, Zamora recounts an early part of his journey.

*

There were nine of us before Grandpa left. In Ocós, we were eight. Now, Marta and Don Dago are gone. There’s six of us left. The Six, I call us. It’s my secret. Like we’re the Power Rangers, Sailor Moon, or the kids with the rings that bring Captain Planet to life. We’re a team. Our mission: get to La USA.

We sit next to each other surrounded by twenty to twenty-five strangers who don’t talk to us. It’s still dark; my watch says it’s five a.m. The sun is nowhere over the mountains, it doesn’t even peek through the mangroves and coconuts that cover the creek. The sky behind the Mexican men at the back of the boat is getting lighter and lighter. Hopefully, by the end of the day, we will be in México, the only country left between me and my parents.

Everyone huddles up, shoulder to shoulder, knee to knee, with the person next to them. Everyone holds their backpacks on their knees, their arms wrapped around them. It’s mostly men. Adult men about the same age as Chele, Marcelo, and Chino. Exception: teenagers (no facial hair). There’s also a few men who look older than fifty, closer to Don Dago’s or Grandpa’s age. Four women, counting Patricia. And two other children—shorter than everyone else and flat-chested like Carla and me. No one talks.

What separates us from the drivers at the very back of the boat is a double line of three bright-red gasoline barrels. Each barrel is almost my height. I’m far from them, but I can smell the gasoline, almost like paint, like glue, like smelling highlighters. At first, it smells good, but soon, it’s overwhelming. Behind the barrels are the biggest motors I’ve ever seen, about half as tall as the drivers, who are the only people standing up.

They’re also the only Mexicans. I thought that when one of them talked to Don Dago, but confirmed it listening to them talk to each other. They sound nothing like us and say “carnal” a lot. They haven’t talked to us yet. As they row, they keep looking at the shores until the creek gets wider and the ocean waves get louder and louder. Near the motel, their oars touched mud. Now it’s just water.

I try to find the moon, but it’s nowhere. I want something big to look at. In two days it’s supposed to be full. The calendar in our room had little red moons next to the black numbers. But nothing is up there. And it’s cloudy. I hope it doesn’t rain. I can’t stop thinking about what the locals told Marcelo. Everything is gonna be ok.

I try to find the moon, but it’s nowhere. I want something big to look at.

It’s warm already, even though there’s a slight breeze that sends salt through my nostrils, on my tongue, on my cheeks. The waves are bumpier, it’s not smooth like it was behind the motel. We’re closer to the delta. It reminds me of taking a boat from my hometown to the ocean; that was the scariest part, the bumps. The Mexicans aren’t rowing. One of them, the one with the round hat, walks up the boat toward Carla and me. When he leans closer I can see his beard is sprinkled with white hairs. He’s old. Sunglasses hang from his neck, tied with a shoelace, and as he leans, they almost hit my forehead.

“Plebe,” he says. His voice, his speech is different. Even more pronounced than Don Dago’s. He sounds like the people in old Mexican movies, the ranchera ones Chente appears in. “Here,” he says quietly. His voice reminds me of Grandpa’s. Hard. Direct. He opens his fist, and two small white pills shine bright in the dark-blue light like eyes looking up at Carla and me.

“So you don’t puke,” he says, extending his big hand toward us. Carla grabs one first. Then he puts his hand closer to me, and I grab mine. He hands us water from a bottle tied with a rope to his belt. Before putting it in her mouth, Carla looks at Patricia, who nods. I look at Patricia and she nods again.

The small pill leaves a bitter streak on my tongue. I don’t feel anything. He says nothing else but smiles, his teeth crooked and with big gaps in between each top tooth. The man hands Patricia one pill también. As she swallows, the man walks away, makes his way toward the front of the boat where the other children and women sit. We watch them take their pills. He makes his way back down to the middle of the boat, near us, and starts talking.

“¡Listen up!” His voice pierces through the sound of the waves and through the slight breeze. “There are a few rules.” Everyone’s head is turned toward him. “Once we turn the motors on, we will not stop. We will stop near sunset to give you a break, so if you have to piss, piss now.” He speaks slowly. We listen to every word. “If you need to shit”—he stops there, looks around—“do it now, or hold it. We will not stop.” He waits around for questions, but no one asks anything.

Then someone who sounds like us asks from the front of the boat, “¿When we leaving, pues?”

“When the other two boats get here,” the Mexican says. I thought we were going to stop at the beach, stretch our legs, but no. “We’ve done this before, don’t be scared,” the Mexican continues, looking at Patricia, Carla, and me, then at the other women and children. His face is skinny and rectangular, and his hat is made of a light-brown cloth. No one asks anything, so he walks to the back of the boat.

It’s almost 5:30 a.m. The sun’s rays begin to highlight the edges of the waves—it’s beautiful, the rest of the water looks like dark-blue Jell-O. From up the river, we see two boats approaching. They’re identical to ours: no canopy, filled with people, and big red gasoline barrels near the back. The boats are painted white with a dark-blue rim and are nameless, which makes me remember what fishermen say back home: “A boat needs a name, or it sinks.”

The boats drift until they float next to ours. We’re so close we could walk between them. The Mexicans at the back of each boat— the coyotes—talk to one another. The other people look like the ones on this boat, mostly men. People my color, some white like Chele, others darker than me, some darker than anyone I’ve ever seen. Some say “vos” like us. Some call me “güirro.” I don’t understand. Others speak something that’s not Spanish. Older men wear long-sleeved shirts and sombreros like the ones campesinos wear back home when they work the corn, cotton, or sugarcane fields. Mostly everyone else wears a dark T-shirt like Chino and Marcelo.

Marcelo is the only one on this boat who wears a tank top, the same dark-green tank top he wore in Ocós, showing off the tattoo on his left shoulder. The shirt makes him look like Rambo, or some other soldier ready for war. I try reading Marcelo’s tattoo, but it’s faded. More than once I overheard Don Dago telling him to cover it up, that people might think the wrong thing. Marcelo didn’t listen, he shows it off like a badge. Some people stand up to pee over the side of the boat like the coyote said, but I don’t have to go, not yet.

It’s gonna be hot today. Marcelo has the right idea with the tank top. I wish I’d brought one. It’s warming up, even with the slight breeze. The coyotes stop talking.

“¡Get ready, cabrones!” yells the younger coyote, wearing the backward baseball cap of a team I’ve never heard of. His voice is not as deep as the bearded coyote’s. His face is round, and he also carries sunglasses tied with shoelaces around his neck. “¡Sit down! ¡Everyone, sit!”

The other boats drift away from ours. All of them turn their motors on. The older coyote tightens his hat—there’s a chin strap he presses into his jaw—and sits. The younger grabs both of the motors’ handles—the motors rumble, a noise that sounds like motorcycles. Everyone looks scared. People start whispering. The people next to us say “Diosito this,” “Diosito that.” Patricia mouths a prayer. Some look up at the sky, their palms opened and facing up. Others grasp the crucifixes around their necks or tied to their belts. Others pull out cards with saints on them. I pray I see my parents soon. I say, Cadejo, Cadejito, protect me.

We’re moving closer to the delta, closer to the open ocean, where there’s a break of big waves with white on their edges. Each wave feels harder and harder against our butts. The bump bump bump like a heartbeat that doesn’t rest. Our boat is first in line. The coyotes both stand up. It seems like they’re trying to read the waves, like the boat drivers do back home. I feel tingly. Numb. My face stiff like it’s been smiling for too long.

We’re moving closer to the delta, closer to the open ocean, where there’s a break of big waves with white on their edges.

“¡Get ready!” the old coyote screams. The boat waits, wobbles, lulls. The ocean is a small earthquake. My stomach churns like I’m about to puke. The sides of my stomach are an empty plastic pouch of mayo, a used paper plate with food smudged on it, a dirty window.

Then the Mexican with the rounded hat yells at the one with the baseball cap who has his hands on the motors’ handles. “¡Ya! ¡Recio! ¡With everything! ¡Everything!” he screams at the baseball cap.

The boat jolts. The old coyote yells at everyone, “¡Grab the boat! ¡Grab the boat!” Patricia holds Carla with one hand, the boat with the other. I hold the boat with both hands. Bump bump bump, the waves bigger as they crash against the front. It’s hard to hold on. Some scream. The older men with sombreros grab them before they fly off. I grab the people next to us. A shirt, pants, anything. Every single wave hurts our butts. A black cloud of gasoline smoke thickens the air. The smell. The boat breaks each wave, then there’s a big one—

We’re up in the air. The sky gets closer. Everyone holds their breath. Some fall into the middle. Then it’s over.

The bumps quieter, smaller. But the smell stays. The stench of gasoline thick in our nostrils.

“¡That’s it!” the old coyote says, celebrating, showing his crooked teeth. It happened so fast. We’re over the break and in the open ocean. The shore is behind us. The volcano. Ocós. The cement buildings. The tower where the men smoked. Houses turning their lights off for morning. We watch the other boats break through the big waves separating river from ocean. The motors are loud. Everyone’s smiling, crossing themselves, praying. Chele, Marcelo, and Chino pull out cigarettes and smoke. Everyone looks more relaxed.

My butt hurts. The motor in the background. Rrrrrrrrrr. Splash. Rrrrrrrrrr. Splash. Rrrrrrrrrr. Splash, salt water on our faces. Wind on our chests. The sun warms our exposed skin. The old men keep their hands on their hats—it looks tiring. Some take them off for fear they will fly away. The sun is completely over the mountains, and everything on the shore, on the water, is closer to the color things are supposed to be. I’m trying not to think about the meters and meters of water, layers and layers of fish, sharks, alligators, monsters, under us. This is the farthest out at sea I’ve ever been. Nothing will happen to us here. Nothing will come and take us from these boats, throw us overboard. I’m going to land in México. I’m going to see my parents.

______________________________

From the book Solito by Javier Zamora. Copyright © 2022 by Javier Zamora. Published by Hogarth, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

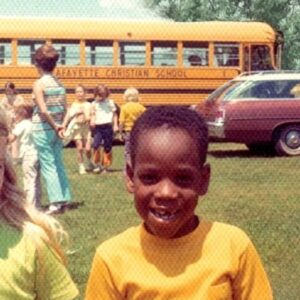

Javier Zamora

Javier Zamora was born in El Salvador in 1990. His father fled the country when he was one, and his mother when he was about to turn five. Both parents’ migrations were caused by the U.S.-funded Salvadoran Civil War. When he was nine Javier migrated through Guatemala, Mexico, and the Sonoran Desert. His debut poetry collection, Unaccompanied, explores the impact of the war and immigration on his family. Zamora has been a Stegner Fellow at Stanford and a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard and holds fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Poetry Foundation. His memoir Solito is out now from Hogarth.