Trieste vs. Milan, Poetry vs. Plot: Beppe Severgnini on the Italian Love—And Need—For Poetry

“Poetry belongs not only to those who write it but also to those who read it and listen to it.”

“I adore prejudices, commonplace cliches

I like to think that in Holland

there are still children wearing wooden shoes

that in Naples they play the mandolin

that you’re waiting for me with an undertone of anxiety

as I change trains between Lambrate and Garibaldi.”

The author of these lines is Luciano Erba, a Milanese poet who lived from 1922 to 2010. The title of the poem is “Linea lombarda” (“Lombard Line”), and it comes from the collection Nella terra di mezzo (In the Middle Ground, 2000). Once you know that Lambrate and Garibaldi are two subway stations in Milan, no further explanation is required.

Poetry picks a corner of reality shrouded in penumbra and illuminates it. We focus our eyes, and we understand. It takes very little. Even the experience of changing Metro trains in Milan summons up memories and emotions.

Poetry belongs not only to those who write it but also to those who read it and listen to it. It proceeds through subterranean channels; it surfaces in society and then dives away out of sight, and never randomly. My feeling is that poetry emerges in moments of crisis and transition—look at Amanda Gorman’s impact on Americans. It’s as if that’s when people feel the need to understand more deeply and clearly, to find a shaft of sunlight in the dark forest of current events. Poetry has this ability. It offers a lightning synthesis that reaches the brain by way of the heart.

When poetry does appear—pulled out of a bookshelf, declaimed on a piazza, tucked into a dedication or a text message—the Italians recognize it instantly.

The turn of the 2020s, the third decade of the 21st century, is reminiscent of the beginning of the 1970s, the eighth decade of the 20th century and a time of great political, economic, and social uncertainty. Then and now, the Italians wanted change, their impatience generated confusion, that confusion produced uncertainty, and that uncertainty demanded consolation. Poetry provided it. We must turn once again to poetry for the help it can provide in the aftermath of a pandemic.

Fifty years ago, the need for poetry was assuaged, in part, with songs by, among others, Lucio Battisti, Fabrizio De André, and Francesco Guccini (listen to them, they’ll help you understand us). But there also existed a thriving poetry scene, and I have proof of that fact in my home. Aldo Borlenghi—a poet, critic, and philologist, a personal friend of the poets Giuseppe Ungaretti and Vittorio Sereni—married an aunt of mine, Franca Severgnini, who worked as a pharmacist. My apartment in Milan was their home before it became mine, and a virtual library of the Italian Novecento was handed down to me. All sorts of things pop out of it; it’s a veritable gold mine of serendipity, where I continually find things I never thought to look for.

A few years ago, while making a public appearance, I made the acquaintance of a man in his mid-seventies, Brianza born and raised. He’d come to the event specifically to talk to me. As a young man, he had studied at the Istituto Tecnico Carlo Cattaneo, where my Tuscan-born uncle, Borlenghi, who’d come to Milan from Switzerland (to which he’d been exiled by the Fascists), had been given a teaching position. The old man told me, “Your uncle had us read poetry in class. At first we made fun of him. Today I say: for many of us, it changed our lives.”

Poetry offers a lightning synthesis that reaches the brain by way of the heart.

It’s not only a lovely way to commemorate a teacher as well as a delicate tribute to poetry; it’s also a useful reminder: even now, we all need evocative food for thought. Poetry is almost never a bestseller, and it’s rarely heard on the radio or seen on television; only social media has offered it a scrap of the space it deserves. But when poetry does appear—pulled out of a bookshelf, declaimed on a piazza, tucked into a dedication or a text message—the Italians recognize it instantly.

It’s as if our long years of familiarity with it—twenty-three centuries, if we count the language we spoke before Italian—have created an unconscious sensibility. We’re a nation of poetic apathists, and we continue to surprise: the world, but first and foremost ourselves.

*

I’ve never been able to pin down the source of my passion for Trieste. I wasn’t born there, I didn’t study there, I haven’t worked there, I never fell in love while strolling along Via XX Settembre or lying in the sun at Barcola. But when I hear “Triéste”—with the first e uttered elongated and narrow, like the eyes of the city’s young women—I freeze. I listen, l look, I read, and I want to understand.

Why does Trieste attract me so powerfully? Is it because it’s so very Italian, so decidedly Austrian, and so notably Slavic? Because it’s Jewish, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox? Because it’s the North of the South, the South of the North, the East of the West, and the West of the East? No, or not only. Trieste attracts me because it’s a poetic city. Rome, Naples, Venice, and Florence are theatrical cities; well aware of their beauty, they show themselves off.

Milan, Turin, Bari, and Palermo are narrative cities: machines made to build plotlines. Trieste, like Genoa and Cagliari, is poetic. And poetry pops up everywhere: from a nook or a corner, from a steep uphill street, from a boulevard, from the many sails of the Barcolana regatta that light up in unison in the bright sunlight.

Poetry picks a corner of reality shrouded in penumbra and illuminates it. We focus our eyes, and we understand.

At home, my books of Italian fiction and poetry are arranged alphabetically by author. With one exception: writers and poets from Trieste. Italo Svevo, Umberto Saba, Giani Stuparich, Scipio Slataper, Pier Antonio Quarantotti Gambini, Fulvio Tomizza, Claudio Magris, and all the others are slapped chaotically together. Every so often I challenge them: come on, reveal to me the secret of your incredible city. Why does Trieste hypnotize outsiders, who forgive it everything, and impassion the Triestines, who forgive it nothing?

And so when I saw the title, La città celeste, and the painting on the cover, I recognized it immediately, my geographic obsession. The book was published in 2021. The author is Diego Marani, a translator and linguist. Born in Ferrara, he studied in Trieste and spent many years in Brussels. In my mind, I called him out, as if challenging him to a duel. Go ahead, I thought, try to explain to me the inexplicable.

Reader, he did it. La città celeste is a coming-of-age story. But the experiences of the main character—his father, anguished and anguishing, an apartment on Via San Nicolò, the study of languages, love stories with two Slovenian women in succession (the blonde Vesna and the brunette Jasna, sisters)— are merely garnishes, side dishes. The main course is Trieste herself, a mixture of peoples, seafront and highland, port and railroad: a mental terminus. Repeatedly, with a sniper’s precision, Marani hits a definition dead center, making me feel just like him: “A test-tube Triestine, the only one in the whole city not waging some lawsuit against Trieste, not harboring a grudge, without a score to settle.”

“[Trieste] always seems to be on a fold in the map,” wrote Jan Morris, one of the authors who knew the city best and understood it most thoroughly. In Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere (2001)—her last book, after which she never wrote another—ends with these words: “Here more than anywhere I remember lost times, lost chances, lost friends, with the sweet tristesse that is onomatopoeic to the place.” She’s right. Trieste has a scent of lost possibilities and opportunities. It’s a place where angels brush past you.

“Cities are women, and it’s possible to fall in love with them, too, and never forget them,” Diego Marani concluded. That’s true, and every Italian knows it without anyone ever having to teach us.

___________________________________

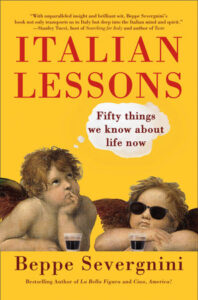

Excerpted from Italian Lessons: Fifty Things We Know About Life Now by Beppe Severgnini. Copyright © 2022. Available from Vintage, an imprint of Penguin Books, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Beppe Severgnini

Beppe Severgnini is an acclaimed columnist and an editor of Italy’s largest-circulation daily newspaper, Corriere della Sera. A longtime Italian correspondent for the Economist and a frequent contributor to the New York Times, he has traveled all over the world. Among his books are the New York Times bestseller La Bella Figura: A Field Guide to the Italian Mind, Off the Rails: A Train Trip Through Life, and the international bestseller Ciao, America!: An Italian Discovers the U.S. He lives with his family outside Milan.