Each of us has an immediate, olfactory connection to our grandparents, who emit the musty clouds of age; hallways and bedrooms smell like dust, or mothballs, or liniment. In my case, they smelled like food, and my connection to them grew during the weekend mornings of my childhood, when my parents and I walked into the lobby at 602 Avenue T, which reeked, perpetually, of chicken fat.

For years, the building’s resident super was a Hasidic rabbi named Lipshitz, who regularly took long, ambling afternoon walks down Ocean Parkway with his wife and their eight daughters in tow. Lipshitz, who my grandfather detested—Lipshitz the Goniff, he called him—was still there when I, the building’s last tenant whose legal right to rent the apartment fell under the archaic rules of New York City real estate law, moved in. When we passed each other in the lobby, Lipshitz glared at me from head to toe, like I was treyf—unkosher, unacceptable, unclean—since I didn’t have to gain his approval before taking up residence. Everyone else in the building was ultra-Orthodox and had been since the building was built in 1933; that many people cooking that much griebenes under one roof for more than 60 years had taken its toll. Although Lipshitz took pride in the sparkling cleanliness of the hallways and the lobby, over time, the essence of schmaltz had been sucked into the pores of the place. When I moved in in 1991, the building still stank; I feared for my clothes. I was certain that my two cats would stink like a pair of fat Shabbos pullets.

“Can’t anything be done about the smell?” I asked Lipshitz when I handed over my first check for the $142 a month rent. He took it from me gingerly, like I was a leper.

“Maybe you could get out,” he said. “Nobody wants you here anyway.”

I looked at him in silent rage; this man from the old country, this specter from the past wanted me gone, banished from his building like it was his own personal shtetl.

But I didn’t want me there either; it had been a last resort. Cheap rent, a few blocks from the subway, a place for me to get my bearings after a bad breakup with a woman that nobody knew about.

“We own it in perpetuity,” my father promised when I began to receive regular notices of eviction from the building owner, who wanted to turn it into a co-op like the rest of the apartments in 602. 5H was the last rental holdout.

“We don’t own it, Dad—I’m paying monthly rent.”

“You’ll stay and bring your husband and raise your children there,” my father explained while we were in the car, driving to housing court in downtown Brooklyn; Lipshitz and his boss were evicting me, to free up the apartment for sale, but my father was counting on it.

“Are you delusional?” I gasped, looking over at him. “I have to return to my life in the city. I’m never going to live there permanently—”

He pulled over into a bus stop and glared at me.

“There has been an Altman here since 1933,” he said, his face flushing a deep red. “You are the last one. This is our family home, our link to the past, to who we once were. It is your responsibility to maintain that link.”

I opened up the passenger door, unbuckled my seat belt, and vomited into the street.

* * * *

The first night I stayed alone at the apartment, my father’s phone call set off the ringer amplifiers that he’d left attached to the ceiling in every room—my grandmother had gone stone deaf in her later years—and when he checked in on me, the walls and windows shook, and my cats hid in the bowels of the coat closet. He was calling, he said, to give me some advice.

“Whatever you do, don’t turn on the stove,” he said.

“What if I want to cook?”

I stood in the foyer, phone in hand, in front of my grandmother’s Sony Trinitron, sucking down a glass of the Bombay Sapphire gin that my father had deposited on a kitchen shelf next to a rusting 1947 Tzedekah box raising money for the new State of Israel.

“Use the top burners, but not more than two at a time. And don’t light the oven. I’ll take you to Macy’s tomorrow to buy a microwave.”

I was suddenly single, alone after a bad breakup, living in my long-dead grandparents’ apartment with all of their things—their clothes, their pictures, their hairbrushes, their lipstick—and I couldn’t even roast myself a chicken without blowing the place up. I couldn’t bake a pie or a loaf of bread. I couldn’t broil a piece of salmon or make a lasagna or a brisket or oven-braise root vegetables or a leg of lamb. I couldn’t even bake a potato.

We went to Macy’s the next night, and my father bought me a microwave big enough to be an end table.

“There’s a roast chicken setting,” he said, pointing to its front panel. We took it back to 602, plugged it in, heated up a mug of water, and instantly blew one of the two fuses that powered the entire apartment. Lights flickered. A popping sound and a faint whiff of electrical smoke filled the air. We stood in the kitchen in our winter coats and stared at each other in silence, like two children.

“We should go out,” he said.

We went to a nearby Chinese restaurant; we ate at a small table near the bar and got drunk on gin Gibsons.

“So where do I buy food?”

I plucked the dark red cubes of roast pork, familiar to me from our Sunday night Tung Shing House dinners of my Queens childhood, from between a tangle of sprouts and slivered carrots and celery and I ate them one by one.

“There’s King’s Highway,” he said, shoveling shrimp and lobster sauce onto his plate.

“Anything closer?”

“Avenue U. Near the F train. Your grandmother never went there,”

“Why not?

“Italian.”

Grandma Bertha once stole a piece of bacon from my breakfast plate when my father brought her up to Boston to visit me at college. She ate steamed lobster at The Jolly Fisherman on Long Island, prawn cocktails, and ham and Swiss sandwiches and cheeseburgers. But 602 was off-limits to anything that hadn’t been prayed over, sanctified, and koshered, as if the very roof over their heads was tenuous, and hanging by a slender, fraying thread directly connected to God.

Avenue U was a four-block walk from 602, but it didn’t matter because I didn’t cook. After work on a Friday night, I came back to the apartment starving for pizza, and ordered a pie from a nearby place called Tony’s; Lipshitz gasped when the delivery guy passed him in the hallway carrying the grease-stained, white cardboard box with the word SAUSAGE stamped on its side. I ordered cartons of Szechuan pork from a local Chinese takeout place and ate them at my grandparents’ flowered oilcloth-covered kitchen table with the Coney Island Parachute Drop hovering behind me out the window; I dumped the clumps of cheap, double-fried meat onto a mountain of steamed white rice I’d spooned onto my grandmother’s magenta-flowered dessert plate, and shared the table with the smudged, black-and-white pictures of the marching Israeli children that wrapped around the Tzedekah box that stood dusty and forgotten on a corner cupboard shelf since she began stuffing it with folded-up dollar bills after the war was over. I put my fork down and shook the box; it rattled like a maraca, noisy with hope.

A week after moving in, I got sick with the kind of flu that makes you want to die; when it hit, I retreated to my grandfather’s massive horsehair bed and stayed there for days, until a dull ache in my stomach reminded me to eat. Feverish, I pulled on a sweatshirt and jeans and stumbled across Ocean Parkway towards Avenue U, right into a wall of marching, tight-lipped, unsmiling older women pulling empty grocery carts behind them. I followed them south, under the elevated F train, to the Italian neighborhood where my grandmother never went.

There was a cheese shop and a tiny greengrocer selling baskets of fresh fava beans and bunches of spicy, bitter puntarelle. There was a pork and sausage store that also sold fresh and dried pasta, and massive, round cans of salted Sicilian anchovies; a bakery selling fresh semolina bread dotted with sesame seeds; a fishmonger; a butcher whose window display included ducks with their heads on, chickens with their feet attached, and rabbits that had been skinned down to the circles of fur around their ankles, like the booties on Phyllis Diller.

A scrim had lifted, and the sepia world I was living in was gone. Every day, I did my shopping on Avenue U, and every day, the little old Italian ladies in black grilled me about what I was making and how I was making it. When I said I couldn’t bake anything because the oven might explode, they shook fingers in my face and said You don’t need no oven.

At the pork store and the greengrocer, I bought anything I could cook on top of the stove: there were thick coils of fennel and garlic sausage that I simmered with red wine, grapes, and thyme, and then seared in a hot, dry skillet; fava beans that I boiled and shelled and mashed into a topping for the semolina bread that I toasted in my grandmother’s oil-slicked cast-iron frying pan; I wilted the bitter puntarelle in a pot of salted, boiling water, and tossed it with orecchiete cooked in the vegetable water, and folded giant spoonfuls of thick, fatty sheep’s milk ricotta into the warm pasta. In the coming 18 months, I left my cookware packed in boxes in the living room and raided my grandmother’s dusty cupboards: her ancient aluminum pots clattered on the stovetop, their bottoms rounded and dimpled with age. I steamed what needed steaming in a white enameled colander set over a small pot of boiling water. I wine-braised butterflied pigeon in my grandmother’s old Teflon matzo brei fry pan covered with a warped cookie sheet; I drank cheap red wine out of the tiny, four-ounce milk glasses of my childhood; I drizzled warm, quartered figs with the dregs of my grandfather’s Slivovitz that I found sitting in the depths of the hall closet, buried behind torn Klein’s of Fourteenth Street shopping bags bursting with the fading letters that my father had written to his parents from the Pacific during the war, when he was 19. And every night for 18 months, I ate my dinner while sifting through piles of dog-eared photographs of long-forgotten cousins in Europe, of my acne-pocked teenage father who longed for his own father’s affection, of my grandparents on the beach in Coney Island in 1917, right after they were married, of my great-grandmother in Novvy Yarchev, right before the Nazis came.

When I moved out, I took nothing with me; I left with my cats and my clothes and my cookbooks—still sealed in their moving boxes from the day I arrived—and tucked a stash of my father’s wartime letters into my knapsack. On my way out, I stopped into the kitchen and picked up my grandmother’s Tzedekah box, which I had been using as a paperweight against the breezes coming in off Coney Island; beneath it was the sheaf of wrinkled, handwritten notes that I’d scrawled while standing in the stores on Avenue U with the stern-faced Italian ladies. I stuffed the papers into my bag and left the Tzedekah box where I’d found it when I moved in, like a sentinel.

The old refrigerator heaved a death rattle when I reached behind the damp, cool coils and pulled the plug out of the wall. I turned the light off, stepped out into the hallway, and closed the door behind me; I reached up and touched the mezuzah, attached by my grandfather 60 years earlier, and said goodbye.

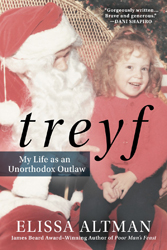

From TREYF: MY LIFE AS AN UNORTHODOX OUTLAW. Used with permission of NAL. Copyright © 2016 by Elissa Altman.