Tracy K. Smith on Liberty

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

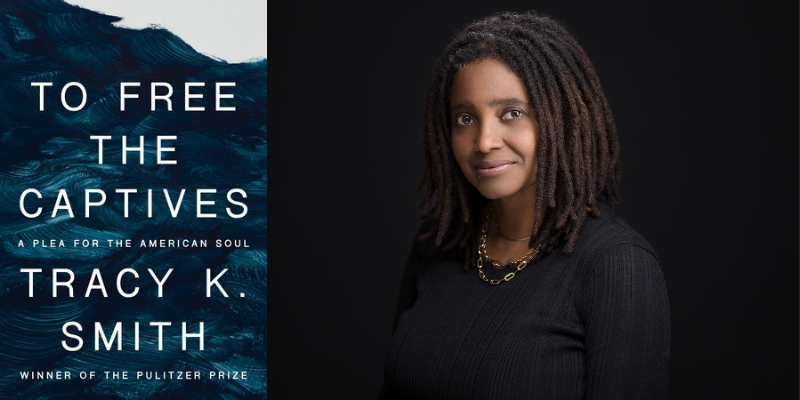

Pulitzer-Prize winning writer Tracy K. Smith joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss the difference between being “free” and being “freed.” She suggests that citizens of the United States fall into one category or the other. The first appear to have descended from those who were always free. The second descend from those who were acted upon by those in the first category. Smith talks about the research she’s done to understand the roles her forefathers played in this country’s armed conflicts and the connections between the military and our historical understanding of freedom. She reads from her new collection of essays, To Free the Captives.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

V.V. Ganeshananthan: In the second essay of this collection, you write, “My error, I now see, had been believing that I was Free, that freedom had long ago been won for me. … For in reality, I am not Free but rather Freed, a guest in the places — we might just as easily call them institutions — where freedom is professed.” So for you, what is that distinction between free and freed? And what role does that play in your thinking throughout the book?

Tracy K. Smith: It’s a subtle distinction, and largely invisible, as I understand it, but I think we are actually obedient to it in many ways. As I see it, the American imagination has been configured in such a way that some of us are considered to be, and to always have been, free. I believe those are people who appear to descend from histories of power, ownership. In this country, that means enslavement, forced migration of others, other such deliberate acts or “pacts,” as I like to think of them.

And the people in this category enjoy freedom that goes largely uncontested. Whereas the others of us appear to descend from histories of being acted upon by the free, through enslavement, through the consequences of colonialism. For us, I believe there is a lower ceiling and a nearer border that governs what we can reasonably ask for or expect or critique in this country. Most of the time, I think we move along without a lot of reminders of this, but they’re present. For me, they became perceptible during the year 2020 when so many of us were thinking about justice and thinking about how the institutions, including the nation that we belong to, might choose to change in order to offer more to more people.

Whitney Terrell: At the top of the show, Sugi and I were talking about the concept of freedom as espoused by people like the members of the Freedom Caucus, or Ron DeSantis and former President Trump. In that same essay, you have a definition of freedom that, to me, fits more with their idea of freedom. You describe that freedom as, “A willful act, a pact with erasure and forgetting.” Can you talk a little bit about that?

TKS: Yeah, I think it comes back to this notion, this fabrication of what the free descend from and are entitled to. The myth in this country is that it’s an innate status, that certain people arrived here with freedom and continue to operate under the presumption of it, when in reality, we know there’s always been conquest. There’s always been violent territorial injustice that has facilitated dominion of some over others.

Sometimes I feel like the way that the word freedom is used in our country is that it operates as a shield for all of the deliberate machinations that actually disenfranchise others, and maybe allow a kind of conscience-absolving belief that what is being done is not out of the ordinary, that the reason some people don’t have access to guaranteed polling situations, or the reason some people feel themselves to be left out of decision making in this country isn’t because there’s injustice, but rather, they’re just not entitled to as much freedom as others.

They don’t know what to do with it. It will be squandered. It will be wasted. And maybe this is a conversation that is operating at a more audible decibel level right now. But I don’t think it’s ever gone silent.

WT: I feel like that connection with erasure reminded me of the reactions that those groups had to projects like the 1619 project, to teaching history and being honest about the history of enslavement in the United States. And what they’re saying is we want the freedom to not have to know about that, we want the freedom to continue to erase that. Is that what’s part of that definition as well?

TKS: Absolutely. The full history reveals that this is something that was warred over and stolen. And how can you act in good faith? How can you demand what you believe is coming to you if this is the backstory that’s shadowing your position here. And so history is a real threat to the mythology of freedom in this country. History is always a threat to mythology, which I see as something that rescues people and decisions from the reality of the choices that set them into play or the forms of violence that enabled them.

VVG: There are so many American institutions that have deployed the concept of freedom in one way or the other, but maybe no American institution more associated with that term than the American military. You talk a lot about your family’s connections to the military, which we’re going to get to, but I want to talk first about why that connection between freedom and the military exists. Is it legitimate? Yes, our military has fought against fascist dictators like Hitler and Mussolini, and in that sense, prevented this country from being governed by them. But today, I frequently hear people talk about the military as preserving our freedom. And I wonder what that means. I mean, did Operation Iraqi Freedom preserve anyone’s freedom? It doesn’t seem that way to me.

TKS: Yeah it’s really interesting. I think that all of the different narratives that we claim make it possible for all of these different functions to operate simultaneously. I imagine I have ancestors who fought in the Civil War. So, enslaved Blacks who honestly and legitimately believed and trusted that what they were fighting for was freedom from enslavement and a full allotment of humanity, in the eyes of this nation. And in their experience, those would have been not the abstractions that we experience them as now, but utterly concrete facts of its daily existence.

I write a little bit about my grandfather and great-uncle, who I know fought in World War I, and uncles and my father, who were also enlisted later, in later conflicts. And I think that oftentimes for Black soldiers and soldiers in minoritized communities, what is being fought for is the right to those very same things, to participate and be seen as a full citizen of this country. I know that for my father and his brothers, enlisting in the military also seemed to offer an on-ramp into middle class life or something close to it. And so those are freedoms from certain circumstances, for example Jim Crow segregation, that they would have been born into.

I know that participation in the service didn’t actually yield all of those fruits for everyone. But I think the motivation was that the government would operate in good faith, and we in good faith could participate in this project of citizenship. But as we’ve been saying, there’s nothing that’s clean. There’s no history that isn’t marred by the leveraging of power over others. I think it’s really interesting. The military quietly reinforces so many of the social hierarchies that we live with in this country, maybe first and foremost a deference to power and a belief that authority is something that we can trust in many cases. But it also invites people who are oftentimes among the most vulnerable in this nation to become complicit in certain of these other choices that you’re talking about: conflicts over resources, conflicts that are going to create devastation in other states, other nations.

And so it’s a complicated set of choices, and I’m not sure that everybody is thinking through them all or has the belief that they can afford to think through them all and choosing the version of freedom that might feel most at hand. And I’m sure that’s not an accident. I’m sure that having citizens from different sectors invested in these conflicts, some of the motivations for which are kept quiet, reinforces forms of trust and authority that serve a few rather than the many.

WT: So I have written in the past about Black soldiers serving in World War II, a lot of people have written about that because, of course, they came back with this horrible irony of returning to Jim Crow. But you write in that first essay about Black soldiers, including your grandfather, who fought in World War I, which is not something I’ve read a lot about. I wondered if you could talk about your research for that and your grandfather’s experience in the war and the experience of these other soldiers, then maybe read to us a little bit from the essay.

TKS: Sure. I didn’t have a lot of the documents from my grandfather’s experience that I wanted, that I wished for. I was able to locate enlistment records and get a sense of where he sailed off to serve. An old portrait of him probably around the time that he enlisted, or perhaps from his time in France, surfaced. That was just such a gift, a miracle.

But in order to get a sense of what his experience might have been like, I had to look into archives of other people’s experience. And one place it was really useful was the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture, which many people, many private citizens, descendants of World War I veterans, have offered up their fathers’, grandfathers’, great grandfathers’ archives, to what I think of as like the wider history. And so one thing that I learned is that very few Black soldiers were in combat units, and the reason for that was not an accident. It had to do with, on the one hand, fear of giving Black men weapons, on the other hand, the prevailing stereotypes that would cast Blacks as shiftless, as lazy, as cowardly, as untrustworthy. And so most — though not all — Black soldiers ended up in labor units or service units, which is where my grandfather was.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Madelyn Valento. Photograph of Tracy K. Smith by Andrew Kelly.

*

To Free the Captives • Life on Mars • Such Color • Ordinary Light • Wade in the Water • My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree • There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love • The Body’s Question • Duende • American Journal: Fifty Poems for Our Times (Ed.)

Others:

Fiction/Non/Fiction, Season 4 Episode 9: “Tracy K. Smith and Kawai Strong Washburn on Biden’s Debts to His Base (Especially Black Women)” • The 1619 Project • Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture • W.E.B. Du Bois • “The Glaring Contradiction of Republicans’ Rhetoric of Freedom” by Ronald Brownstein|The Atlantic, July 8, 2022 • “Trump’s Second-Term Plans: Anti-‘Woke’ University, ‘Freedom Cities’” by Andrew Restuccia | The Wall Street Journal

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.