Tracking Down My Literary Idol to a San Francisco Commune

On Translating Irving Rosenthal's Deeply Weird

and Wonderful Sheeper

By the turn of the millennium I had been living in Paris for a dozen years, had gotten married and divorced, and had joined a literary journal, Les Épisodes. I worshipped writers possessed of panache, who threw their insolence, silliness, style, or crudity in your face, so I suppose it is only natural that Sheeper should have found its way into my hands.

I happened upon it in my favorite second-hand bookshop, San Francisco Book Company, on Rue Monsieur-le-Prince, and though I was familiar with the author’s name—Irving Rosenthal—from his association with Naked Lunch, parts of which he had published in the late 1950s as editor of the Chicago Review and then Big Table, I didn’t know he had written a novel of his own.

As a physical object Sheeper resembled no book I had ever seen: it had a dust-jacket with an etching of an enormous grasshopper in a sunburst, wings and antennae extended; a dark blue cloth cover with a gold embossed mandala/rose window bearing the title, each letter isolated in its own compartment; a drawing on the half-title of a female praying mantis seen from behind in a menacing posture with forelegs and wings spread; and a woodcut on the title page—the caricature of a bearded Jew with two hats on his head, a third in hand, and slung over his shoulder, a bag out of which peeked a sleek, presumably Gentile child’s foot—crowned by the caption, “THE POET! THE CROOKED! THE EXTRA-FINGERED!”

I read the first sentence, and it hit me like a thunderbolt: “My mother used to whip me with a wooden coat-hanger, or with her hand, which I liked better, because it meant that she got some of the sting, too.”

I thought, no matter what follows, that opening line is worth the price of admission, so I bought the book and took it home.

I spent the rest of the afternoon and most of the night reading Sheeper with a growing sense of awe and wonder. Around two in the morning, Rosenthal made a pass at me:

Would you understand it if I plunged my hand right through this notebook into time, process, and distance so that it emerged out of the very printed page you are reading and reached down to grope you? […] Do you like this book enough to press it to your crotch or breast? Kiss me.

I put the book down, looked around the room. I was alone—or was I?

I read on:

Have you been touched by a book whose author still is living? Love him back. Seek him out and help him get over his shyness. Love from the past can kindle our spirits like gold and rubies set a thousand years ago, but live skin yearns for the touch of skin.

I finished reading Sheeper that night, and, as the saying goes, it changed my life forever. I became obsessed with publishing a translation of it—starting with a few sections in Les Épisodes, and then the whole book with the lucky French publisher who would have the gumption to buy the rights.

But first I had to track down the author.

Online, I found the University of Delaware’s Special Collections, which housed the Irving Rosenthal papers, including 28 letters from Tangier in the 1960s to one Ira Cohen. The biographical note was tantalizingly vague: “Little is known about American editor and author Irving Rosenthal. Born in 1930, Rosenthal is counted among the Beats […]. After traveling to Morocco, Spain and Greece, Rosenthal returned to New York in 1964. His activities thereafter are unknown…”

I asked a poet I knew in NYC if he could get me Ira Cohen’s number and he did. Ira was very easy to connect with, very eager to talk, and he told me that Rosenthal was living on a commune in San Francisco and had dropped out of the literary scene entirely.

“When you write to Irving, send a picture of yourself.” “Seriously?”“You could write to him,” Cohen said, “but I’ll have to ask him permission to give you his address. You know, he’s fussier than most people. He refused to sign my copy of Sheeper, and I was practically that book’s midwife!” Then Cohen asked, “Are you cute?”

“According to whom?” I said.

“I don’t know, women, f******…”

“Well, I guess so.”

“Okay then, when you write to Irving, send a picture of yourself.”

“Seriously?”

“Of course!”

*

Sheeper is a book that won’t sit still. It pokes, prods, provokes; irreverent, kaleidoscopic, Jewish, and wacky, it’s a bildungsroman about—among other things—passion, idealism, incest, drugs, homosexuality, black magic, vegetarianism, style, and the romance of writing.

Though Sheeper is outrageously misogynistic, several women I know have been bowled over by its beauty and universality. (Thelonious Monk once said that he had been trying to hate white people for years, “but someone would always come along and spoil it.” I imagine it was the same with Rosenthal and women; his mother was so hateful he decided to loathe all women forever, but he couldn’t help having a soft spot for a good number of them.)

*

Cohen called me back the next day with good news: Rosenthal was amenable to my writing him a letter. So I did, sending along two issues of Les Épisodes and a picture of my handsome self and he responded on peach-colored paper, saying that he had no objection to me translating parts of Sheeper for an upcoming issue of the magazine. He gave me his email address, asked for mine, and added that he had written a foreword to Sheeper and revised it—“nothing that a lover of the book would object to or even notice”—after Dalkey Archive Press contacted him in the early 90s with the aim of reprinting it, a project that never came to fruition. (Published in hardcover by Grove Press in 1967, and in a Black Cat paperback edition the following year, Sheeper remains out of print in English to this day. NYRB Classics, if you’re listening…)

Rosenthal sent me the PDF of the new version of Sheeper and I was off to the races, translating the opening pages and telling everyone I knew about the book, convinced I was having a rendezvous with Literary History.

*

That summer we had published the foreword and first three chapters of Sheeper in Les Épisodes when a close friend of mine named Roger—a sixty-ish chain-smoking mythomaniac with a transplanted lung and self-given monikers such as Shithead the Retread, and The Stainless Steel Duke of Dubuque—drove a pickup truck off a cliff in Mendocino County.

I booked a ticket to San Francisco, where Roger was convalescing at his daughter’s house on 23rd Street up near Twin Peaks, and emailed Irving that I would soon be in town “visiting a friend,” asking if I could drop off his complimentary copies of Les Épisodes personally.

Irving answered, “If you want to say more about your friend I am interested.”

I realized that he was wondering if, or hoping, or expecting that Roger and I were lovers; he didn’t know if I was straight or gay, as we had never broached the subject in our exchanges.

Regardless, he had no doubts about his own role, for he added, “Will try to hide clay feet.”

The day after my arrival, and with some trepidation—“You know, this is really not the safest neighborhood in San Francisco!”—Roger’s daughter drove me down to the Mission.

I rang the bell of a white, box-like wooden building; the door opened, and I found myself face-to-face with a pint-sized 70-year-old man in gray sweatpants and a white t-shirt, with a long white beard and thick curly long white hair gathered in a ponytail—a Jewish garden gnome, I thought.

Irving looked up at me and smiled, cooing, “My translator.” He had grayish green eyes and a face my father would have described as “the map of Israel.”

Irving showed me around the commune: a converted warehouse featuring a printing press, a large kitchen/dining area with stainless steel appliances of the sort one would expect in a restaurant, and rooms upstairs and downstairs.

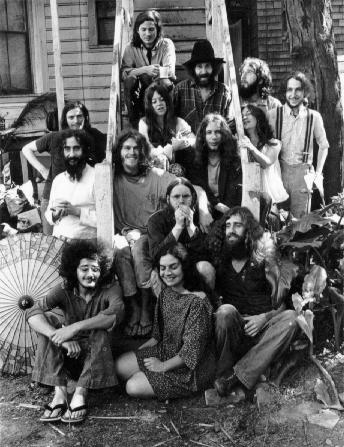

Some members of the Scott Street Commune, also known as the Kaliflower Commune, gathered in the backyard of the Redevelopment-owned Victorian which they occupied from 1971 to 1974. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Some members of the Scott Street Commune, also known as the Kaliflower Commune, gathered in the backyard of the Redevelopment-owned Victorian which they occupied from 1971 to 1974. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

On the top floor next to the library was Irving’s office and private library. When I mentioned a forgotten tortured gay writer from the 60s that I knew Irving had known, he smiled and said, “There’s a section of my library I call Bad Books by Good Friends. Would you like to see it?”

“Of course.”

He reached down and removed a plank from the very bottom of his shelves, and there, hidden from view, were at least a dozen books.

Sitting on the back deck overlooking a large, lush garden with brick paths, cherry trees, bamboo stalks, and poppies, Irving asked me about my life in Paris. He talked to me about what he and his friends at the commune did—provide emergency and transition shelter, a soup kitchen, and print charts (on their printing press) listing places to find free food, shelter, medical aid and mental health care—and then we went for a stroll in the garden. Irving was wearing red geisha-style platform flip-flops with white socks, and I had my camera, and he let me photograph him.

Here was Irving, continuing to live this philosophy in the midst of 21st-century capitalist America: work anonymously, give things away for free, give up ambitions of fame and wealth.Before I left, Irving gave me two beautifully produced pamphlets he had written, published, and distributed for free over the years: Deep Tried Frees, and Pros in Poetry, and we made a date to go garage-saleing the following Saturday.

*

Roger was not doing well. Though the doctors said that his having survived the accident was miraculous in itself, he had lost over 20 pounds since I had last seen him a month earlier in Paris, his complexion was sallow, and he was on dialysis.

But he seemed happy to see me, and I was pleased to note that his recent misfortunes had done nothing to dampen his sense of humor:

“You know what the good thing about puking is?” he asked me the morning after my visit to Irving’s commune.

“What?”

“You don’t have to wipe your ass afterward.”

Trying to make myself inconspicuous around the house I took Roger’s granddaughter and her dog out for walks to Tank Hill as often as possible; at night I immersed myself in Irving’s pamphlets.

I learned that his communal stance was based on the Diggers, an 17th-century group of English Protestant radicals who wanted to create rural egalitarian communities and whose beliefs had been adopted in pockets of 1960s San Francisco, where, thanks to folks like Irving and Richard Brautigan, they had briefly blossomed. I thought idealism of that sort had disappeared, but here was Irving, continuing to live this philosophy in the midst of 21st-century capitalist America: work anonymously, give things away for free, serve only the people you can talk to, give up ambitions of fame and wealth, abolish banking, bookkeeping, and bill-collecting.

House belonging to the group formerly known as the Kaliflower Commune at 23rd and Shotwell Streets in San Francisco. Photo taken April 2019, via Wikimedia Commons.

House belonging to the group formerly known as the Kaliflower Commune at 23rd and Shotwell Streets in San Francisco. Photo taken April 2019, via Wikimedia Commons.

He also wrote that charging money for art was like renting “the sky to seagulls,” and that the “most honest and loving” thing a writer could do was “to be silent once the message is out,” which would perhaps explain why he never wrote another book, ceasing all literary warfare after launching that initial masterful missile.

*

We made a date to go garage-saleing, as Irving and his friends liked to say, the following Saturday (garage-saleing being the only kind of “sailing” that Irving, who had a rich friend with a boat he often sailed on the Bay, could afford to do).

I cajoled Irving into talking a little more about his book, and he told me that the gut-wrenching, pathetic “Letter From Mother” in Sheeper—2,500 words of bitterness, recriminations, and sadness in awkward, misspelled English—was a collage of several letters he received over the years from his mother, and never answered.

Emboldened, I asked him who the enigmatic Professor X was based on (“Professor X complains that my book is about style and that’s all it’s about. He is right.”), but got put in my place: “I don’t feel comfortable revealing my sources,” Irving said to me witheringly.

At one of the sales I bought a biography of Paul Bowles, whom Irving had known and clashed with in Tangier. When I found him in the index and showed it to him Irving’s eyes flashed, his hands went up, and he said, “Enough.”

*

In 2004, Hachette Littératures published my translation of Sheeper. Though a reviewer in Le Monde called it a masterpiece, the words “deafening silence” most aptly describe its reception. But Irving seemed pleased; he told me several times on the phone how happy he was to have his book appear in French, since the French language and culture were of such vital importance to American poets. I called him regularly, and our long-distance friendship flourished; Sam, his right-hand man would often answer, saying, “This is costing you a fortune,” which it was, and then after a few pleasantries, go off to find the gnomic master. Meanwhile I would sit there listening to the faint silence on the line like soft rain, wondering if Irving was making me wait like that on purpose, the grand diva delaying her entrance.

He was always enthusiastic though, telling me about his work with various soup kitchens, what he was reading, and the new lost people he had rescued from the street, describing them in glowing terms, calling them “creatures,” talking about what meds they were on, if they were psychotic, and the high hopes he had for them.

*

That winter I got a small prize from the French culture ministry for my translation of Sheeper and used the money to return to San Francisco and visit Irving. I stayed at the commune and was even given my own key. At the time, Irving was writing a memoir about underground filmmaker Jack Smith, who had been a close friend of his in the 60s.

After asking me to look at it, he handed me a red (actually pink) pencil. The master editor wanted my edits! In exchange, I asked Irving to read some poems I had recently translated from Swedish, and so we spent a few days reading and improving each other’s work.

One morning I was walking with Irving on Valencia when he saw a soaking wet, stained white t-shirt on top of a newspaper vending machine. Beaming, he picked it up and placed it in a plastic bag to take home.

“All my clothes I find in the street, or are given to me,” he told me. “And you know what?”

“What?”

“I found a foolproof way of fixing shoes that are too big. Look,” he said pointing at the ground, where I saw that the toes of his white sneakers had been pierced through with a bolt, making them a snug fit for Irving’s tiny (clay?) feet.

He seemed so chipper that I broached the subject of his signing my copy of Sheeper, which I had brought with me to San Francisco for that purpose.

Irving’s face fell. “I’ll think about it,” he said.