Tracing the Family Legacy From My Suffragette Grandmothers

Adele Logan Alexander on Researching Her Mixed Heritage

In 1983, Ms. magazine published an article I’d submitted about “finding” my paternal grandmother, who was a pioneer in the woman suffrage movement. The editors said this: “Adele Logan Alexander is working on a book-length biography of Adella Hunt Logan.” Since then, I’ve written many other things, taught history, acquired a headful of gray (I like to think silver) hair and a glorious rainbow of grandchildren. But I continued pursuing that intriguing political activist, that little-known, outspoken “black” woman who looked white, for whom I was named.

I learned about Adella and more about our country’s grievous war during which she was born and the next half century in the southern United States. I explored relationships among her kin, as well as theirs with both obscure and renowned figures of that era. Among them, my relatives talked about the fellow they admired, respected, and often saw in New York City but called “Dr. Dubious”; another, the brilliant scientist whom they warmly referred to as “Uncle ’Fess” Carver; and the family’s Alabama neighbors, “the Great Man,” Booker T. Washington, and his obdurate spouse.

There was a long-gone President Roosevelt too, not the Democrat who in my childhood I thought always had and always would hold that omnipotent position but an earlier one, a Republican, whom my grandfather Warren Logan seemed to have known rather well. Ultimately, I also realized that my grandmother Adella Hunt Logan’s legacy as she worked to acquire the vote for women was her way of trying to give them a voice, of empowering them.

And looming over their lives was Jim Crow, the ugly nemesis whom they scorned, defied, and struggled to outsmart.

My father and aunts often reminisced about Tuskegee, a fabled place sometimes called the “Hither Isles,” which they both loved and loathed, and about Atlanta University, where most of them had attended school. And before those venues, I learned, there was Sparta, Georgia.

I slogged through versions of Adella’s story that were conventional history and other fictionalized ones but ultimately determined that this should be neither a traditional biography nor a novel. Rather, it’s an intricate memoir about an era, places, and mostly a woman to whom I’m irrevocably bound. Here I’ve tried to reveal and reconstruct Adella from a plethora of archival and published materials but more through what my family and others boldly trumpeted, whispered, or surreptitiously confessed.

To do that, I’ve unraveled many snarled threads, spun them out again to weave into a comprehensible whole the often perplexing documentation that I accumulated. I’ve speculated about how and why results that I know for certain might have come about and tried to understand and interpret the incredible accounts that I heard and believed over the years but can’t incontrovertibly prove.

Some of Adella’s stories were inspiring; others were almost too painful to retell.

As I position my grandmother in her world, I’m reminded of phrases we hear and voice today: “Black Lives Matter,” “Equal pay for equal work,” “My body, my choice,” “Votes for all,” and “#MeToo.” The times, words, and players change; the issues and their urgency do not.

I grew up in a family whose members proudly considered and spoke of themselves as “Negroes.” They healed, taught, and counseled “Our People,” identified with and staunchly defended “the race,” never boasted of their Native American or white “blood,” but were mostly blue-, green-, or hazel-eyed and paler skinned, narrower featured, and straighter haired than many of my Jewish friends at school and my diverse, upper-Manhattan neighborhood’s Italian American cobblers and greengrocers. And those relatives who looked “white” all had darker-skinned spouses. It didn’t seem unusual to me. That’s just how my world was populated.

I also heard about my father’s “mystery uncle” Thomas Hunt (he roared with laughter about having an “Uncle Tom”), who’d “disappeared” in California, where he saw his even whiter-looking but black-identified sis- ter Sarah “by appointment only.” And once a year, my own uncle Paul came from “way out west” to visit us.

Even as a child, I sensed that his siblings loved, disdained, and mistrusted him in roughly equal parts. Living in the Big Apple, I surely knew no one else whose uncle was a forester and lived in Oregon: a faraway, mythical realm.

In past generations, I learned, there had been other legendary relatives: someone called Judge Sayre; his “wife,” Susan Hunt (one of my greatgreat- grandmothers); and their daughter, known as “Cherokee Mariah”—her name pronounced with a long i and spelled with an h.

Interracial hybridity was and is a phenomenon bred deep in the American bone

During my earliest years, a pale and frail old man whom my father and his sisters called “Dad” came north every December. Only once, however, did he bring along his wife, about whom my aunts hissed, “She’s not your grandmother! Georgia is.” I already knew that Georgia Stewart Bond, who often lived with us, was my mother’s mother and my beloved Nana. But that other woman, that unwelcome visitor, they confided, was the wicked witch who’d long ago exiled my then eight-year-old father from his Alabama home.

Georgia Bond’s older daughter, my maternal aunt Caroline Bond Day, had written an awesome tome, which was our family’s secular Bible. Titled A Study of Some Negro-White Families in the United States, it began as her Harvard-Radcliffe master’s thesis in anthropology. It’s filled with photographs, among many others, of various Sayres, Hunts, Logans, and Bonds.

Arcane designations, “1/4 N, 3/4 W,” “1/8 N, 1/8 I, 3/4 W,” even “4/4 W,” appear below them. Interracial hybridity, Carrie had demonstrated in the 1920s, wasn’t something that suddenly would make its disquieting appearance in the late 20th century. Rather, it was and is a phenomenon bred deep in the American bone, sometimes accompanied by dire warnings from fearful or angry white folks about the threat of “mongrelization.”

Recent scientific advances and knowledge about DNA have complicated but also confirmed this old-but-new phenomenon. We need to better understand the similarities with and differences between the children of our recent, post–Loving v. Virginia generations and the myriad pre-Loving offspring, born as a result of sometimes (fortunately) true loving or (unforgivably) rape or comparable coercion.

In “the old days,” they and others like them didn’t call themselves “mixed,” “black,” or “African American” but “Negroes.” A few of them, however, “passed” and dwelt uneasily in the white world, where the menacing gargoyles of exposure, shame, and expulsion always lurked.

Several summers when I was young, I was taken to visit my aunt Carrie in North Carolina. Only years later did I learn that my capable, tan-skinned mother circumvented the indignities, discomfort, and perils of segregated train travel, and our antagonist Jim Crow, by purchasing in advance our round-trip tickets for a first-class Pullman roomette, not in the South (impossible!) but rather in New York City’s open-to-all urban cathedral: Pennsylvania Station.

I had no siblings or close cousins, so as everyone’s only child, usually there were no contemporaries for me to play and talk with at family gatherings. The adults thus had little choice but to include me in their conversations (if they didn’t, I listened and participated anyway), as they drank champagne or scotch on the rocks, smoked Chesterfields, and flat-out adored me but also impressed on me “our responsibilities.”

My aunts played carols, classics, and jazz on their baby grands, cooked in a garrulous flock, ate caviar, lox, sukiyaki, or juicy slabs of watermelon, collards, “trotters,” pig tails, and “everything but the squeal.” They served up tasty morsels of gossip and wisdom and adages such as “learning will empower you,” “know the law and use the law,” “always carry a hatpin,” and “a pretty face can be a colored girl’s curse.”

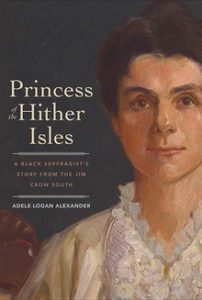

They rarely mentioned her name, but Adella Hunt Logan hovered over everything. Her haunting oil portrait first hung on one aunt’s wall, then another’s, then my parents’, then (and still) my own. Her children found it painful to talk about her, but for years, I didn’t know why. And even now, I can’t quite remember how, when, or from whom I learned that she’d left them.

This search for my elusive forebear leads me to think more about intergenerational bonds. One of the most significant ties I explored was that between Adella and her own grandmother Susan Hunt. The links between me and Adella, whom I never had the privilege of knowing, and with my maternal grandmother, Georgia Bond (who’d been Adella’s friend and fellow suffragist years before their children, Arthur and Wenonah, who’d ultimately become my parents, were born), are vital to my memoir.

Those old relationships also seem to connect me to my grandchildren. This story is for them and, someday, for their eagerly awaited progeny too. Ultimately, the question wasn’t whether I’d tell Adella’s story—I had to tell it—but when and how. Finally, it became clear that the narrative should begin with Susan.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Princess of the Hither Isles: A Black Suffragist’s Story from the Jim Crow South by Adele Logan Alexander, new from Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Adele Logan Alexander

Adele Logan Alexander taught for many years at George Washington University. She is the author of Ambiguous Lives: Free Women of Color in Rural Georgia, 1789–1879 and Homelands and Waterways: The American Journey of the Bond Family, 1846–1926.