Toward an Alternative Canon of Trauma Literature: A Reading List

Chantal V. Johnson Recommends Books That Move Beyond the Trauma Plot

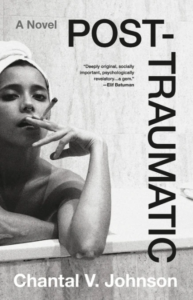

My debut novel, Post-Traumatic, follows Vivian, a lawyer in a psychiatric hospital who begins to confront the psychological and interpersonal aftermath of her violent childhood after a dramatic family reunion. In drafting the book, which explores post-traumatic consciousness, I sought a new path for writing about extreme experiences. I rejected traditional versions of trauma fiction—the sentimental family saga, the book of lyrical fragments, the ghost girl narrative, and the graphic, harrowing coming-of-age novel—in favor of writing that is clear-eyed, darkly comic, and cerebral.

I also wanted to avoid certain genre tropes: I refused to extensively detail abuse or to center a perpetrator in my narrative, and I didn’t write from the perspective of a child or a passive, silenced character. Instead, my novel features dynamic adult survivor best friends with strong points of view. Vivian and Jane are black feminist stoner intellectuals who riff about their traumas, engage in cultural criticism, and chat about moral duties to abusive family members. Despite their (serious) challenges, my characters are cheeky, analytical, self-aware, and very much alive.

As I wrote, I sought out art that takes stylistic risks with dark material. Despite critical grousing to the contrary, there are actually plenty of subversive books about trauma that reject easy pathos and martyrdom, books that aren’t written in otherworldly registers, and books that don’t peddle trauma porn. You just have to look harder for them, because they often get less attention than middlebrow fare, and many are published by independent presses. The books on this list constitute an alternative canon of trauma writing. They are funny and smart, elliptical and digressive, provocative and mean. They encourage us to move beyond the traditional pieties of the genre, offering approaches to writing about trauma and its aftermath that are aesthetically singular, dynamic, and new.

Brontez Purnell, Since I Laid My Burden Down

This is a short, darkly funny picaresque of loss and survival. The main character, DeShawn, is a black gay punk who returns to his Alabama hometown for his uncle’s funeral. Once there, he reflects on his chaotic upbringing in the community he still loves. The book is structured around the deaths of boys and men that DeShawn has known, but while it’s an inventory of losses, it’s not depressing. Topics like abuse, addiction and suicide are covered swiftly and matter-of-factly, but Purnell leavens this material through humor, well-drawn minor characters, and DeShawn’s tenderhearted insights. “He learned that the only way to beat an enemy bigger than you is to survive them. It’s hard. It warps the soul. But it is a strategy.”

Virginie Despentes, Baise-moi

The ultimate rape revenge novel, Baise-moi is a swift descent into female antisocial mayhem. Manu is a tough slacker who drinks heavily and curses a lot. Nadine is a sex worker who watches porn obsessively and hates her vapid roommate. We meet them in short, alternating chapters written in a sarcastic, irreverent style that can only be described as Very Gen X. After Manu is raped and Nadine’s friend is murdered, the pair “manhunt brazenly” for sex, then go on a killing spree. Throughout the novel, Despentes describes violence in prose that is blunt and unsentimental. She takes the image repertoire of pornography and violent cinema and applies it to men, who are mocked, sexually objectified, and murdered without guilt. “Got to stay alive,” Manu says at one point. “Do anything to stay alive.”

Percival Everett, The Trees

The Trees is a darkly comic police procedural crossed with a supernatural race revenge story. In Money, Mississippi (site of the murder of Emmett Till) white people are being killed in grotesque ways; the same mysterious black corpse is found at every scene. Two big-city black detectives, Ed and Jim, are dispatched to investigate. They find a town mired in the racial codes of the past, and they greet it with anthropological humor, noting that Money is “chock-full of know-nothing peckerwoods … living proof that inbreeding does not lead to extinction.” In this book, white people are both the victims and the butt of the joke. As the violence spreads, the book evolves into a resonant tale about the political and spiritual import of writing and storytelling.

Myriam Gurba, Mean

“The post-traumatic mind has an advanced set of art skills,” Gurba writes in her tragicomic memoir, Mean. (In a way, this line sums up my entire aesthetic philosophy.) The book begins with an account of the rape and murder of a woman named Sophia, who haunts the narrator as a tragic counterfactual, then swerves into a chatty, bold account of Gurba’s Southern California youth, her own violent assault, and the miracle of survival. Gurba is a master of gallows humor and high-low pastiche, tossing off phrases like “avant-garde molestation” and “stranger rape makes me think of Camus” that upend expectations of trauma writing.

Gayl Jones, Eva’s Man

Eva Medina Canada is one of the most subversive black women characters in the history of American fiction. When this tricky and provocative novel begins, Eva is in prison for committing a gruesome act of violence against her lover, Davis. The book alternates between the present, where Eva refuses to explain her actions to various interlocutors (her cellmate, her psychiatrist, and the police) and an episodic accounting of the sexual abuses Eva has experienced in her life. In declining to offer a clear rationale for Eva’s crimes, the book rejects psychological and narrative pressures toward trauma resolution and character legibility in favor of preserving Eva’s autonomy and mythological cool. (“I’m Medusa… Men look at me and get hard-ons. I turn their dicks to stone.”)

Jana Leo, Rape New York

Post-Traumatic is in dialogue with feminist visual artists whose work explores gender-based and intimate violence: Ana Mendieta, Nan Goldin, Jana Leo, and myriad others. Leo is a conceptual artist whose memoir begins as a story of a home invasion and rape, but expands outward to become an analysis of NYC real estate speculation, landlord negligence, and the relationship between crime, space, and power. Immediately following her rape, Leo began taking photographs of the material evidence left behind: her bed, a plastic cup, her rapist’s cigarette butts, and her own body, becoming an archivist and investigator of her assault. To support the memoir, Leo assembled her photographs, police and legal records, therapy notes, and interviews with her assailant into a public archival exhibition, emphasizing rape’s far-reaching, public reverberations.

Anne Tyler, Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant

I’m breaking my rule about family sagas by including this here, but it’s a rich novel about family dynamics and the varied ways kids respond to unpredictable, angry adults. After her husband abandons the family, Pearl Tull raises her three children alone: sometimes, she lashes out at them violently. Later in life, she can’t figure out why they all seem to resent her: “They were so frustrating … closed off from her in some perverse way that she couldn’t quite put her finger on. … She wondered if [they] blamed her for something.” The novel is presented as a series of quickly-paced life sketches, isolating the specific incidents that shape each family member’s perceptions and motivations.

Pola Oloixarac, Mona (tr. Adam Morris)

Mona starts as a wickedly funny, refreshingly disrespectful satire of the literary world and veers into apocalyptic terror. When we meet Mona, she’s heavily medicated and flying to Sweden to attend a book award ceremony. Throughout the book, she follows the search for a missing Peruvian girl, brags about her exploitation of American identity politics (“playing the part of an overeducated Latina adrift in Trump’s America” leads to academic opportunities), vapes, cracks jokes, and judges people. But there’s an atmosphere of darkness here: Mona is covered in bruises from an attack she has suppressed, and she’s seeing weird things. Then, at the awards ceremony, something Very Weird happens.

Anna Burns, Milkman

A completely original exploration of individual and community survival strategies in the face of political violence and sexual surveillance, Milkman is probably my favorite novel of the past decade. Set during The Troubles in Northern Ireland, the novel follows an unnamed 18-year old girl who dissociates from the chaos of her world by engaging in solitary activities, namely, “reading-while-walking.” The girl is stalked by an older paramilitary man known only as “the milkman,” but her community misinterprets harassment for a consensual affair, and the escalating rumors lead to fatal consequences. The book is written in knotty, digressive, obfuscating, and often very funny prose, as Burns highlights the moral clarity and deep political knowledge that can emerge from surviving political and gendered terror.

______________________________________________

Chantal V. Johnson’s Post-Traumatic is available now via Little, Brown.

Chantal V. Johnson

Chantal V. Johnson is a tenant lawyer and writer. A graduate of Stanford Law School and a 2018 Center for Fiction Emerging Writers Fellow, she lives in New York. Post-Traumatic is her first book.