A Loaf of Peter Kazimirs

Peter Kazimir looked miserable in sleeveless black shirts. The fitting room’s slatted door was draped in unhelpful layers of baggy, drop-arm, and slashed tees and tanks, all black, and the sales clerk kept tossing more cuts and sizes on top of them, but the color flattened him, and fundamentally, he was a gangly, sallow monkey with arms too long for his torso, and the solid loaf of Peter Kazimirs extending forward and back in the facing mirrors, infinitely multiplied, promised he would never be anything else. He banged out of the fitting room and on to the men’s apparel floor but stopped short when he saw Francisco wasn’t there.

Fran, Fran, he called over the mannequins and shirt racks, reddening. It didn’t take much, these days—three weeks after their breakup—for Peter to feel abandoned. In giant ads on the department-store columns, giant, beautiful people leaned forward out of steel-blue voids, their glances heavy and smoky.

Fran, severely: What? I was looking at sockies.

Peter hugged the mess of black clothes to his chest. Nothing fits, he said.

Fran wore a cut-off band shirt and rubbed his arms to warm himself. The mall, like all of Miami, was over-air conditioned. It was a muggy, glaring, boiling summer outside, the kind of weather meant for fleeing; it was a grayer, cooler summer in Berlin, where they were headed in a week for Peter’s birthday. Peter was turning twenty-nine and although Fran had left him—they were kaput, split, Fran had moved out all his stuff—still Peter hadn’t let Fran out of the trip. The tickets were nonrefundable, and he needed Fran there to help him get into Collider.

Collider, where everyone wore black, was the club where people like Fran went—scruffy, sulky queers looking for heavy synth beats and faceless sex in a corner—but it was so underground and real, and admission so coveted, that straight men held hands in queue and sissied their voices just to have a shot at the door. It was the world capital of hypnalectronica, and though the club cultivated a strict code of silence, through the cracks came whispered stories of veil-lifting, of visions of alternate universes.

The door policy was strict, too: nothing but black, no large groups, don’t talk or laugh in line, don’t look too clean. No nice shoes, but boots, sneakers, shoes you could dance in for eight hours. Someone had designed an app that would look at you through your phone’s camera and tell you if you’d get in, but Peter already had a healthy persecution complex and didn’t need his devices turning against him. Fran had gotten into Collider each of the four times he’d visited Berlin and would get Peter in, too—given the proper wardrobe.

Fran had been reluctant about Peter’s self-makeover; Francisco K. Bazán, Esq., had his lawyerly misgivings. Just be yourself, he’d said, in his unruly Cuban accent. But for the entire two years and one month of their relationship, Fran had lobbied for Peter to be somebody very different from himself, and it was too late now to switch to platitudes.

They’d met in New York at an LGBT lawyers’ meet-and-greet: Peter, the paralegal at a one-name divorce shop, and Fran, the junior associate at a white-shoe Midtown firm. Neither one had bored the other, always a promising sign. Both were pleased to find someone at the event who looked with any interest above the horizon of gay professional ambition. Fran struck Peter as something beautiful and barely contained: his long, aristocratic face was freshly shaved but already shadowing; his black hair was combed flat, but wavy, and his bushy brows unplucked. He had a master’s in Philosophy of Science and a Feynman diagram tattooed across his collarbone, visible when he leaned close and loosened his tie. Peter’s knees went buttery, Fran led him into a bathroom stall and yanked his pants down, and Peter burst into tears and confessed in breathy shudders how he was sick of one-night stands, and he wanted a boyfriend, for once, a real boyfriend. Fran, mortified and offended, listened gallantly enough. It was a testament to them both that Fran had taken Peter’s number and had called him anyway. But for two years and one month, Fran seemed to wait in that stall for the Peter who’d followed him there, convinced there was another, truer man concealed under all his romantic hysteria. Someone who’d go out with Fran to techno parties, to leather bars, to protests and punk shows. And Peter had taken up the humiliating task of explaining he’d given Fran the wrong idea; he really was conventional—homonormative—cliché. He really did want to shop for bathroom fixtures together and sit on the same side of a restaurant booth. He wanted to see La Traviata in box seats, like in Pretty Woman, or meet at the top of the Empire State Building, like in Sleepless in Seattle, and not because he’d failed to grasp the false consciousness of the heteropatriarchy, but because he’d spent his life being shown and then denied this way of being in love, and now he was a grown‑up, and he could get the things he saw on TV. So, they’d tried it Peter’s way. Peter saved up for a new suit, and they went to a gay bar styled as a private club, with a snobby dress code and potted rubber trees, and bartenders in tight tuxedo shirts and black velvet bowties, and warm lamps reflected in mahogany paneling. The crowd skewed older and elegant. Peter drank gimlets and warbled about the Metropolitan Opera, and Fran wondered if the universe was a hologram, until Peter went to wash his hands and when he came back, Fran was furiously explaining to a pearl-haired man in a silver double-breasted that he wasn’t a hooker. The silver man called Fran coy. And that’s what the bar was, they realized: all the well-dressed young men of color hung beside mature white gentlemen like this asshole, and while Fran sometimes passed for white, his accent gave him away. That night, Fran didn’t want to be touched. When they did have sex, in the months after, dark emotions humidified the room: jealousies, resentments, a grave dominance from Fran and a cringing sweetness from Peter that shamed them both. Differences clarified. Fran chafed at monogamy and Peter lost color at the idea of cruising. Fran smoked and Peter asked him to quit. But when Fran got a job in Miami, Peter followed him—to risk everything for love, what could be more exciting?—and together they leased a high-ceilinged one-bedroom in Brickell, and Fran left him ten weeks later. At the time there were brush fires raging in the Everglades and the sky was a foggy, nuclear orange, blowing with ash. One afternoon, they’d gone out for Cuban coffee with an old friend of Fran’s, J.B., a Haitian butch activist with mild dwarfism, and J.B. and Fran had railed together over a recent profile of gay newlyweds in New York Magazine. The men in the photos wore matching, pastel sweater vests and identical cowlick haircuts; they were young, smiling, tidy, their skin white as candles. One posed with an old book on the couch, while behind him his husband gleefully vacuumed. J.B. fumed: This isn’t radical, this isn’t queer. Fran mimed vomiting. Out on the patio, they squinted into the bruised air and Peter spat ash from his lips. He said, But what if this is what they want? Fran looked at Peter with pain and reproach, the way he did whenever Peter told an embarrassing story about himself. Peter asked, Is it so wrong to want to be normal? Even with J.B. right there, who would never be let into that word, normal, Peter had asked, Is it so wrong to want to be normal? And so, as they drove back to Brickell, in the blur of ashfall, Fran apologized to him (in that seething, accusing parody of an apology) for not seeing the truth of their relationship sooner.

As if the truth of their relationship were so inevitable, and not something hidden in the dark palm groves in parks, late at night, where Peter, trembling, now hunted for it alone.

Peter had kept the Brickell apartment, and by day it wasn’t a problem. He subbed as a music teacher for several Catholic schools and rehearsed with the local Gay Men’s Chorus. But at night, the apartment pushed him out. He drove and cruised the college campus bathrooms or wandered the obscure lawns of Paradise-Bird Park. Asking himself: Is this really so terrible? Had this been so truly impossible, when he was with Fran, for him to even try? Maybe the distance between him and Fran hadn’t been unbridgeable after all. In the dark, Peter hardly knew himself: “Peter Kazimir,” who’s that?

Peter hadn’t told Fran about any of his nights in the park but was tempted to, whenever Fran hinted that Collider wasn’t Peter’s scene. Be yourself—but in Collider there were glimpses of alternate realities, in which Peter might be another man entirely.

Fran needed socks so they bought socks. The department store’s PA system hyped a sale on foundations and concealers. Peter lingered over the underwear packages and their photos of chiseled, headless torsos. If I wear these, he joked to Fran, waving the box, will my chest look like this? Peter had a runner’s body, a handsome body that bottomed out into gawkishness the longer one looked. In high school, a modeling scout had once approached Peter in a mall but by the end of the conversation had taken back his business card. Fran hated it when Peter told this story.

__________________________________

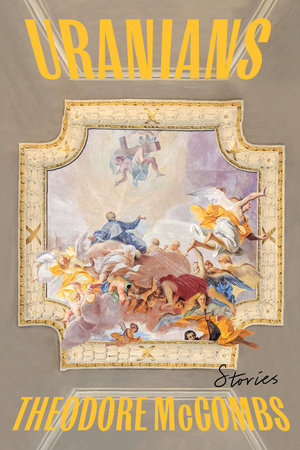

Excerpted from “Toward a Theory of Alternative Lifestyles” in Uranians: Stories Copyright© 2023 by Theodore McCombs. Published by Astra House. All rights reserved.