Toni Morrison on Craft, Inspiration, and the Time She Met Obama

Sarah Ladipo Manyika and Mario Kaiser Talk to an American Literary Icon

For weeks, I had been wondering what she would be like. It was one thing to have encountered Toni Morrison through her writing and to have watched her lectures and interviews, but another to meet her in person. Having just written a book about a seventy-four-year-old woman, I am curious to see what Ms. Morrison reveals about her experience of older age. I had heard that she is wheelchair-bound and often in pain. I hope she won’t be in too much pain (any pain) on this day.

The first thing that strikes me when I meet her is that she looks like one of my friends. You know that feeling when you see someone and think, “Wow, this person is just like so-and-so!” Ms Morrison has the same light complexion, wide-set eyes and thick hair as my friend, the documentary filmmaker Xoliswa Sithole. All but one of Ms Morrison’s silver-gray locks are hidden beneath her beret.

The lone lock pokes out, resting on the nape of her neck. But it’s her presence, more than the physical resemblances, that most reminds me of my friend, making her feel familiar. She exudes confidence from an erect and still posture, from her large stature. She is regal even when, as she occasionally does, dabbing at a watering eye.

I begin by asking how should we address her. Does she prefer Professor, Doctor, Mrs., or Ms.?

“I like Toni,” she says, smiling.

Her smile portends a playfulness and openness that will remain one of my lasting memories of our conversation. Twice during the interview, we are interrupted by friends or family, and on each occasion she introduces us as “friends.”

I’ve known of Toni’s sense of humor both from her books and from watching interviews, but I’m surprised by how much she will make us laugh. She frequently jokes about herself and sometimes about others. Occasionally, she does both simultaneously, such as when a friend drops by with Easter flowers and has to squeeze past us to give her a hug. “You’re too fat, you’re like me!” she exclaims. This ability to joke with others and laugh at herself not only reminds me of people I’m most fond of, but it’s a trait that I most associate with Nigerians. Toni is also prone to laughing at moments that are sometimes the opposite of funny, and this too feels familiar, as a mechanism for enduring what is otherwise traumatic.

I claim Toni as an honorary Nigerian, and she may well be, originally—Igbo, Yoruba or any of the many ethnicities that make up Nigeria. Like a true Nigerian, she is also fond of exaggerations. She talks of publishers who “beat you up” over titles and boasts of a great-grandmother, Millicent, who, she says, is probably “still alive.” Toni is not bitter in her old age, which was something I’d wondered about while reading God Help the Child and sensing cynicism or, like the old woman in her parable, just keeping her distance from younger generations. On this day, at least, she’s not bitter.

*

…This is Toni.

*

LADIPO MANYIKA: One of the refrains in your books is the tension between memory and forgetting—forgetting as a way of overcoming. It’s in Beloved, with this repeated line: “It was not a story to pass on.” It’s in God Help the Child, where you write that “memory is the worst thing about healing.” How do you deal with this tension?

If you know something at the end that you didn’t know before, it’s almost wisdom.

MORRISON: In order to get to a happy place—what I call happy, even though people are dropping dead all over my books—is the acquisition of knowledge. If you know something at the end that you didn’t know before, it’s almost wisdom. And if I can hit that chord, then everything else was worth it. Knowing something you didn’t know before. Becoming something. There are certain patterns in the books and in life that look like they’re going one way. And then something happens and people learn. God Help the Child, which I thought was a horrible title…

KAISER: What title would you have given the book?

MORRISON: I think I gave it one. I don’t remember what it was. It was beautiful!

LADIPO MANYIKA: Why did you not get your own way?

MORRISON: Because they beat you up.

LADIPO MANYIKA: Isn’t that one of the privileges of winning the Nobel Prize—that you can tell people what to do?

MORRISON: No! [She imagines an argument with her publisher.] “Go fuck yourself, this is my title!”—”No, you don’t get to get that!” They think they’re doing you a favor by publishing it, even though they’re making tons of money—and will forever. After I die, after my children die, my grandchildren, they’ll still be making money. I worked in that industry for a long time. I’m unimpressed.

*

LADIPO MANYIKA: What was it like to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Obama? And what did he whisper in your ear?

MORRISON: Were you there?

LADIPO MANYIKA / KAISER: No, we saw the video.

MORRISON: He did whisper in my ear. And I’ll tell you, this is important: I didn’t know what he said.

KAISER: You seemed very pleased.

MORRISON: I knew then! But soon as I left, I thought: What did he say? I was so embarrassed! I went to Paris, and the guy who was the ambassador to France, I told him that story. I said, “He whispered in my ear, and I don’t know what it is. Something’s wrong!” And he said, “Listen, I had a forty-five- minute conversation with him, and I don’t remember a word.”

LADIPO MANYIKA: You were awestruck.

MORRISON: I think that’s it. But when I went to the party, my son was my date. He said to Obama, “You said something to my mother, and she doesn’t remember. Do you remember what you said?” And Obama said, “Yeah, sure I remember, I said, ‘I love you.'” [She covers her face with her hands and pretends to be sobbing.] I can see why I forgot that! I forgot it in the way that you can have a conversation with somebody that you really like or who is really impressive. And it’s so impressive that you just blank.

LADIPO MANYIKA: Let’s talk about your friend James Baldwin.

MORRISON: Oh, yes!

LADIPO MANYIKA: Baldwin once said, “The role of the artist is exactly the same as the role of the lover. If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see.” How do you see the role of the artist?

MORRISON: Oh, it’s funny that he says that. Jimmy. What I’m going to say is going to sound so pompous, but I think an artist, whether it’s a painter or a writer, it’s almost holy. There’s something about the vision, the wisdom. You can be a nobody, but seeing that way, it’s holy, it’s godlike. It’s above the normal life and perception of all of us, normally. You step up. And as long as you’re up there, even if you’re a terrible person—especially if you’re a terrible person—you see things that come together, and shake you, or move you, or clarify something for you that outside of your art you would not have known. It really is a vision above, or beyond.

I think an artist, whether it’s a painter or a writer, it’s almost holy.

It’s hard to think of paintings, particularly, any other way. I can’t imagine how they do that. I mean, what’s the connection between the thing you’re doing and your mind? That’s why criticism is so awful. Not all of it, but much of it. Because the language of the criticism can’t quite reach the plane where the artist is.

LADIPO MANYIKA: Do you name your characters, or do they name themselves?

MORRISON: They name themselves. I have sometimes written characters with names that were wrong, and they never came alive. I have to ask them, “What’s your name?” You just wait and something clicks—or not. And, if not, the writing feels clunky, or they don’t talk. Sometimes it’s just the opposite. When I wrote Song of Solomon, there was this woman in there named Pilate. And once I envisioned her, she never shut up. She really took that book over, and I just had to stop her. So, I said, “You have to shut up, this is not your book!” She has one scene where she’s mourning her granddaughter and she says, “And she was loved.” That’s all the space she got. Although she’s influential, she doesn’t talk.

KAISER: You were baptized a Catholic when you were twelve years old, and you took the name Anthony, which later became Toni. Saint Anthony was a towering figure in the scripture.

MORRISON: Saint Anthony of Padua!

KAISER: He was known for his forceful preaching, and he’s the patron saint of lost things. What are the lost things you would like to bring back?

MORRISON: Two things. One is my son. And there are certain periods in my life I’d like to live over.

KAISER: Is there one period in particular?

MORRISON: Yeah, undergraduate school. There were some very good things with that place, and I learned a lot. I was in this little theater group, and we used to travel in the summer. It was the first time I’d been in the South—the real South, not the Washington DC type. I remember when we got to a hotel and the faculty figured out that it was a whorehouse or something like that. So one of them went to the phone booth. Remember they used to have phone booths? He looked in the back of the phone book to find a Black preacher, which you could because it would say AME, African American Zion, or something. He found one and called them up and said that he was there with some students from Howard, and that they needed a place to stay, because there’s no places for Black people.

The preacher said, “Call me back in fifteen minutes.” And he did, and he had gotten some of his parishioners to accept us. I went with a girl, stayed in this woman’s house. It was fabulous! God, she had dried her sheets on bushes that had that odor. Oh, it was heaven! And they fixed us fabulous food. We tried to give them money, but they wouldn’t take it. So, we put it in the pillowslip.

KAISER: The story is reminiscent of Frank Money, the protagonist of Home, when he’s looking for a place to stay.

MORRISON: Oh, yeah. There’s that Green Book he uses, which I have a copy of, which was where Black people could stay. You know, I didn’t identify him as a Black man until my editor said, “Nobody knows if he’s Black or white.” And I said, “So?” And he said, “Toni, I really think it’s important.” So, I gave in. But I was interested in writing the way I did in Paradise, in which I announce color: “They shot the white girl first.” But you don’t know who that white girl is. And that was very liberating for me because sometimes you can say “black” and it don’t mean nothing. I mean, unless you make it mean something.

That was a learning thing because of the other side of town, where blackness was purity—and legitimacy. See, my great-grandmother lived in Michigan, and she was like the wise woman of the family. She knew everything. She was a midwife. Every now and then, she would visit. This was a tall woman. I mean, she looked tall. She had a cane that she obviously didn’t need. And she came in the house and looked at me and my sister and said, “Those children have been tampered with.” I thought that was a good thing. But she was pitch black, and she was looking at us as soiled, mixed. Not pure. She was pure—pure black, pure African—and we were kind of messed up a little bit. I thought that was interesting, because I had been “othered” since I was a kid—but from the other side.

LADIPO MANYIKA: Can we talk about sex?

MORRISON: Yeah! I’m in a good position to talk about it, since it’s been like a thousand years. What do you want to know?

LADIPO MANYIKA: You are known for writing great sex scenes.

MORRISON: I do! I think I write sex better than most people.

LADIPO MANYIKA: How do you do it?

If you can associate sex with some other behavior that is interesting, then the sex becomes interesting.

MORRISON: The worst thing about sex scenes is that they’re all clinical. They say “breasts,” or “penis” or what. I mean, who cares? The goody part about sex and writing about it and having it is not that. It’s something else. In The Bluest Eye, when she goes all the way, she claws away the skin to get to the ivory—you know, she’s going down. Deep! But if you can associate sex with some other behavior that is interesting, then the sex becomes interesting.

LADIPO MANYIKA: In Beloved, it’s the cornfield, but it’s also the eating of the corn, the suggestiveness.

MORRISON: The corn tops are waving. The guys are looking.

LADIPO MANYIKA: “It had been hard, hard, hard sitting there erect like dogs, watching corn stalks dance at noon.”

MORRISON: Somebody told me that Denzel Washington was asked to be in the movie of Beloved. And he said, “I’m not gonna be in a movie where Black men have oral sex with white jailors.” There was a scene where these men are in jail digging, you know, but they’re all chained. He acted like that was bizarre. And then you read about Choate, this school where everybody was raping all the students from the sixties on. I don’t know why he was so hostile to it. But that’s OK, Denzel! I’m interested in how to make it really beautiful, really intimate, and distributed. It has to be something that everybody can relate to—not just the sex act, but what I’m saying about it. I read other people’s sex scenes and I think, “Yeah, so?”

*

KAISER: You have said that you don’t want to be remembered as an African American writer, but as an American writer.

MORRISON: Did I?

KAISER: Yes.

MORRISON: America? I couldn’t relate to the country. It’s too big. It’s like saying, “How would you think about Europe?” I mean, what? But I was somewhere with Doctorow, the writer, at an event. He was introducing me, and he said, “I don’t think of Toni as a Black writer. I don’t think of her as a female writer. I think of her as…” And I said, “White male writer.” And everybody laughed. That’s what I remember. He was trying to move me out of the little sections. But what was there besides woman, Black? There was only white men. He probably meant to say just a plain writer, you know, a writer writer.

__________________________________

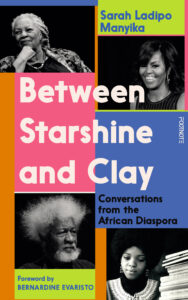

Excerpted and adapted from Between Starshine and Clay: Conversations from the African Diaspora by Sarah Ladipo Manyika. Copyright © 2023. Available from Footnote Press. The full version of this interview as it appears in the book was conducted by Sarah Ladipo Manyika and Mario Kaiser at Toni Morrison’s home in upstate New York on April 15, 2017.

Sarah Ladipo Manyika

Sarah Ladipo Manyika is a British-Nigerian-American writer of novels, short stories and essays translated into several languages. She is author of the best-selling novel In Dependence (2009) and multiple shortlisted novel Like A Mule Bringing Ice Cream To The Sun (2016), and has had work published in publications including Granta, The Guardian, the Washington Post and Transfuge among others. Sarah serves as Board Chair for the women’s writing residency, Hedgebrook; she was previously Board Director for the Museum of the African Diaspora, San Francisco; and has been a judge for the Goldsmiths Prize, California Book Awards, Aspen Words Literary Prize, and Chair of judges for the Pan-African Etisalat Prize. Sarah is a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.