I walked up the steps, between the thickset columns, and into the impressive foyer of the Galer Street School. It was underlit and cathedral cool. Framed photos told the story of the building’s transformation from a home for wayward girls to a single-family residence (!) to today’s ruinously expensive private school.

A little about the building’s restoration. On the floor, in wood inlay, because strait is the gate and narrow is the path which leadeth unto life and few there be that find it, dated to 1906. One hundred and fifty rubber molds were created for the intricate plaster work. Colorado alabaster was cut paper-thin for the clerestory. The mosaic of Christ teaching children to pray required flying in a seventy-year-old craftsman from Ravenna, Italy. When the restoration began in 2012, the big mystery was what had happened to the brass Art Deco chandelier from the early photos. It was found by the guys blowtorching blackberry vines out of the basement. Large blindfolded pigs were lowered in on ropes to chew the chandelier free.

How could I possibly know this? As I entered, the chic architect in charge of the restoration happened to be leading a tour.

On my way to the administration offices: “Eleanor!”

I turned. For the past month, the conference room had become auction central, abuzz with parent volunteers.

“You’re just the person we need!” said the woman, a young mom.

Me? I mouthed, pointing, confused.

“Yes, you!” said another young mom as if I were a silly goose. “We have a question.”

When I graduated from college it never would have occurred to me not to work. That’s why women went to college, to get jobs. Get jobs we did and kicked some serious ass while we were at it, thank you very much, until we realized we’d lost track of time and madly scrambled to get pregnant. I pushed it dangerously close to the wire (no doubt because Catholic Joe, the oldest of seven, was in no hurry himself, having changed enough diapers for a lifetime). I gave birth to little Timby, thus joining the epidemic of haggard women in their forties trapped in playgrounds, slumped on boingy ladybugs, unconsciously pouring Tupperware containers of Cheerios down their own throats, donning maternity jeans two years after giving birth, and sporting skunk stripes down the center of their hair as they pushed swings. (Who needed to look good anymore? We got the kid!)

Was the sight of us so terrifying that the entire next generation of college-educated woman declared “Anything but that!” and forsook careers altogether to pop out children in their twenties? Looking at the Galer Street moms, the answer would be: Apparently.

I hope it works out for them.

I entered the conference room with its giant beveled windows overlooking the play yard and Elliott Bay. A massive table (cut from the center of a maple tree salvaged from the property or some such trendy nonsense, according to the architect) was piled with file boxes and cascading manila folders. I weaved my way through hip-height cardboard cartons with Galer Street T-shirts hanging out, red like tongues. The air crackled with efficiency and purpose. “Where are you? Where are you? Where are you?” the young mom muttered. “Here?” I said.

“You need to find the item number and cross-reference it with her name,” said another young mom.

I went to Japan once and our guide claimed that to them, all Americans looked alike. At the time, I thought, Oh, you’re just saying that about us because that’s what we say about you. But beholding this array of young, glowing, physically fit moms, it occurred to me that Fumiko might not have been messing with me after all.

“Got ridiculous?” said the first young mom.

A young dad (because there’s always one dad) held up a folder. “Victory is mine!”

“You won a latte, you won a latte,” singsonged the first or the second or the third or the fourth mom.

Put these parents in a room with clerical work and zero supervision, and they start acting like the deranged winners in an Indian casino ad.

“You donated a hand-drawn portrait of the winning bidder in the style of Looper Wash,” said one, finally acknowledging my existence.

“That’s you?” asked another.

Like ostriches, they all stopped and cocked their heads at me. “I heard you went here,” said one, taking me in.

“Timby’s mom,” said another, the expert.

Seattle is short on star power. A past-her-prime animator and a Seahawks doctor make me and Joe the Galer Street equivalent of Posh and Becks.

“I’m a Vivian,” said one.

“You’re totally a Fern,” corrected another.

“What are you doing now? ” one flat-out asked me.

“I’m writing a memoir,” I said, heat weirdly building in my cheeks. “A graphic memoir.” It was none of their business, but I kept going. “I have an advance from a publisher and everything.”

The ostriches smiled inscrutably.

On the table, a ring of keys. Each key had one of those color-coded rubber jobs around the top. In my life I’d bought a hundred of the damned things but had always given up because who can put them on without bending a nail? Also on the ring, a neat fan of bar-code tags from Breathe Hot Yoga, Core de Ballet, Spin Cycle . . . And in a personal touch, this young, fit mom had attached a lanyard with her child’s name in baby blocks.

I turned my head sideways. What was the name?

D–E–L–P–H–I–N–E.

I froze.

“Yoo-hoo!” called a young mom.

“You forgot to put a dollar value as to what it’s worth,” said another.

“What what’s worth?” I said, snapping to.

“Your auction item,” put in another. “For tax purposes.” “Oh. I don’t know.”

“We need to put down something,” said the first young mom. “It’s just a few hours of my time.” My breath had become stuck.

Why did I have to see those goddamned keys?

“What’s your time worth? ” This was the young dad, wresting control.

“Literally?” I said. “Per hour?”

Did he mean the hours I spent lying in bed vowing to change?

The hours shopping for organizers that forever remained in the bags? The hours researching mindfulness classes, signing up for them, going so far as parking outside art-gallery-yoga-studios and watching the well-intentioned students file in, only to lose my nerve and peel out? The hours planning to eat dinner as a family, just to end up hunched in front of our screens, every man for himself? The hours steeped in shame that I had no excuse for any of it?

And then, squeals.

The first-graders had burst onto the lawn wearing butterfly wings shellacked with colorful bits of tissue paper. The young moms (and the one dad) turned their backs to me and basked in the slipstream of their children’s spontaneity and delight. The energy in the room shifted from bubbly conviviality to hushed reverence. All the choices these young moms (and the one dad) had agonized over — to work or not work, to marry young or keep looking, to have a kid now or see the world first — had led to hard decisions. And with decisions come regrets. And sleepless nights, and recriminations, and fights with their husbands (and the one wife), and whacked-out calls to the doctor for pills. The “catatonic vision of frozen terror” the poet had called these moments of existential doubt, or certainty, it was hard to know which. But seeing their children now, in this instant, these parents knew in their teeth that their decisions had been the right ones.

So, with a perfectly timed cough, I grabbed that young mom’s ring of keys, dropped them in my purse, and slipped out.

That’s right, I stole them.

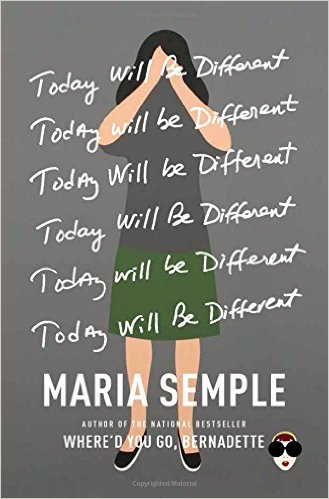

Excerpted from the book TODAY WILL BE DIFFERENT by Maria Semple. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2016 by Maria Semple.