To the Manor Born: On the Rise of Fred C. Trump, Homebuilder

Son of Immigrants, Mogul of Queens

Accommodating the motorcar, in a discrete way beneficial to the urbanism of the street, was the hallmark of Brooklyn’s last great builder of the interwar era—Fred C. Trump, father of the contentious 45th president of the United States. Born to Bavarian immigrants in an old-law tenement by the Third Avenue el, Trump knew he wanted to build at a young age. He worked alongside his mother, Elizabeth, to improve a handful of Queens Village building lots left by his father after his death in 1918.

He learned all he could apprenticing with local carpenters, took night-school and correspondence courses in drafting and the building trades, and later studied construction management and engineering at Pratt Institute. Trump finished high school in 1923, just in time to grab the tail of the 1920s building boom. The very next year, Elizabeth was advertising homes built by her son on 212th Street in Queens Village, and by 1926 Trump had erected 19 “beautiful English type homes” of his own design on 199th Street in nearby Hollis (“Be King and Queen in a trumphome,” shouted his newspaper ads).

He contrived a precarious method to finance construction, selling a half-built house to bankroll its completion and start the next one. Because he was not yet 21 years old, his mother had to sign for him at his first closing. By 1929, Trump had luxed his operation, erecting upscale stucco-and-stone Tudor homes on rolling, park-like acreage in Jamaica Estates—a setting “so like the aristocratic estates of Old England,” gushed the builder in a Herald ad, where one could enjoy “the quiet and sturdiness of country—and yet be right in New York City.”

With the building industry slowed by the faltering economy, Trump was forced to cool his heels running a supermarket he opened on Jamaica Avenue in Woodhaven—one of the first in New York City (later acquired by the King Kullen chain of Long Island). But the Depression brought new opportunities and opened the door to the neighboring borough. Trump got into Brooklyn real estate by buying up the assets of a failed mortgage and title colossus known as the House of Lehrenkrauss.

A German American banking and insurance conglomerate founded in 1878, the firm began trading in what were known as “certificated” mortgages during the great 1920s building boom. “To pay for the residential properties going up all over New York City,” writes Trump family chronicler Gwenda Blair, “mortgage banks and title companies began to ‘certificate’ mortgages—that is, to divide them into shares that were then sold to the general public like so many bonds.” The Lehrenkrauss certificates were popular with small investors and continued to pay a respectable return despite the Depression.

Then, in early December 1933, the House of Lehrenkrauss became a house of cards. The venerable firm, it was discovered, “had been running a deficit operation for years,” writes Blair, “covering expenses and salaries with a haphazard assortment of schemes that included issuing watered stock, writing up mortgages based on either inflated or nonexistent evaluations, selling mortgage certificates worth more than the mortgages they represented, and taking out bank loans against mortgages that had already been certificated.” With the Depression holding down its cash flow, the House of Lehrenkrauss soon found itself underwater.

To pay its furious creditors, the company’s shrinking assets were put on the auction block. Trump and a partner, both outsiders from the wilds of Queens, prevailed against well-heeled, politically well-connected Brooklyn bidders to secure the mortgage-servicing department of the company, which managed a large portfolio of properties on which it held mortgages. One of the Lehrenkrauss assets now controlled by Trump was the Tudor-manse colony of Laurye Homes that Lawrence Rukeyser had begun building in Marine Park. When Rukeyser’s operation went belly-up in 1932, his unfinished dwellings were acquired by the Raemore Realty Company, with mortgages guaranteed by the House of Lehrenkrauss.

With the building industry slowed by the faltering economy, Fred Trump was forced to cool his heels running a supermarket he opened on Jamaica Avenue.

Raemore managed to complete and sell a handful of the homes in spring of 1932. But sales petered out by summer; and when Lehrenkrauss slipped beneath the waves in 1933, Raemore went under with it. Trump lost no time completing the half-built houses; by the end of May 1935 he had sold three properties. Thus was Brooklyn’s greatest real estate empire launched at the far-flung corner of East 33rd Street and Fillmore Avenue, on land farmed since the time of Cromwell and Milton.

Trump next built a battery of 65 attached “brick bungalow” row houses on a site just north of Kings Highway at Schenectady Avenue in East Flatbush, the first of what would become a Trump staple in the years before World War II. The bungalows made for good urbanism, creating delightfully scaled streetscapes that only improved with time as street trees—nearly always London planes—reached maturity. The typical prewar Trump row house sported a roofline punctuated by gables, black steel-frame casement windows with an occasional pane of leaded glass, a small porch, and “a beach-towel-size swatch of front lawn” raised just enough above the ground-plane to inhibit casual trespass.

And, in a departure from the design of the cheaper Realty Associates homes, Trump wisely relegated cars to a common alley behind the dwellings. This not only contributed to the architectural unity of the street, but made on-street parking more plentiful by eliminating that bane of the outer boroughs—driveway curb cuts and the inevitable conversion of front lawns into parking pads. In April 1936 Trump purchased a large parcel from Realty Associates at Cortelyou Road and Albany Avenue, campsite of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus that spring.

By the Fourth of July, he had 400 men digging foundations where elephants and camels had trod just months before, and soon erected the first batch of 450 brick bungalows. What sped this and subsequent Trump projects along was a stimulus program initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s new Federal Housing Administration to jump-start the housing sector. In June 1934 Congress passed the National Housing Act, Title II of which authorized the federal government to serve as guarantor of last resort to banks making mortgage loans, thereby assuming much of the risk in a volatile real estate market.

Banks could now lend up to 80 percent of the value of a property, up to a limit of $12,800, while the interest rate could not exceed 5 percent. With Uncle Sam thus watching their backs, bankers could “turn on the fiscal spigots, and construction could resume.” To assure that it was not backing junk, the FHA issued the first nationwide standards for appraising real estate and assessing the creditworthiness of borrowers, as well as strict guidelines for building design and construction. “Because many areas lacked building codes,” writes Blair, “the FHA put together its own minimal standards for key elements like indoor plumbing, fire protection, sewage disposal, lot size and subdivision planning.”

Trump soon mastered these standards, winning favor with the FHA state director for New York, a Bay Ridge lawyer and Democratic machine operative named Thomas Grace. Impressed by the young man and his plans—and by Trump’s expanding network of political friends—Grace authorized $750,000 in mortgage insurance for the circus-ground venture, enabling Trump to take out the huge construction loans necessary to erect the 450 homes.

Thus sheltered under the FHA’s big tent, Trump followed the circus—literally. In May 1937 he began erecting a colony of 400 homes at Clarendon and Ralph avenues, with a crew of 350 men working day and night with the aid of floodlights. A year later he had another venture under way closer to Kings Highway, adding 300 more homes to his portfolio. By the spring of 1939, Trump had sold some 700 houses in Flatlands; he was just 34 years old. He now set his sights on a large parcel of vacant land near the junction of Utica, Remsen, and East New York avenues in Brownsville.

Fred Trump was as ingenious at marketing his homes as he was in constructing and financing them.

This land, too, had been used—in 1938 and 1939—for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Here Trump rolled out his largest FHA-backed venture yet, speedily erecting 400 homes. By now he was using principles of mass production similar to those that Greve had pioneered a decade earlier at Gerritsen Beach, earning him the sobriquet “the Henry Ford of housing.” By 1940, Fred Trump was the biggest builder in Brooklyn. He erected another 300 homes on East 39th Street and Foster Avenue by Paerdegat Park in East Flatbush, then turned south to Brighton Beach, where he built 200 deluxe dwellings at Corbin Place and Neptune Avenue—this time without FHA backing.

And Trump was as ingenious at marketing his homes as he was in constructing and financing them. He set up an elaborate billboard at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, seen by hundreds of thousands of visitors, and even took to the sea to sell his wares—in a 65-foot cabin cruiser with Trump Homes spelled out in ten-foot-tall letters on twin hoardings. The Trump Show Boat first worked the thronged Coney Island strand on July 8th, 1939. With the city in the midst of a heat wave, beaches were packed.

As the captain drew near the surf, loudspeakers came alive with music, and crewmen began tossing hundreds of inflatable swordfish into the water. Each was stamped with Trump Homes and a figure, from $25 to $250, indicating its value toward a down payment. Like a riot of gulls trailing a laden trawler, swimmers raced into the ship’s wake for the bobbing fish. The music was so loud it could be heard a mile off. Hundreds stood at attention when “The Star-Spangled Banner” played; others rushed to the water when the boat began broadcasting “lessons in ‘aquacading’ or graceful swimming to music.”

Not everyone was pleased—park commissioner Robert Moses, for example. A hater of carnies, hawkers, and shrills, Moses had a police boat stop the craft and issue the captain tickets for operating in a bathing area, advertising without a license, and violating noise ordinances. Trump suggested Moses join him on board. The Show Boat was back out the next day, cruising the beach while Trump and his buddies fished from the stern—their ears presumably plugged.

“Twenty fluke, porgies and weakfish were caught, all while the music was playing,” Trump exulted; “When the music stopped playing the fish stopped biting.” Moses and Trump played a waterborne game of cat and mouse all that summer and the next, the Trump Homes message reaching countless New Yorkers in the process. At a hearing in September 1940, Judge Jeanette Goodman Brill—first female magistrate in Brooklyn—issued Trump a perfunctory fine before inquiring, sotto voce, whether he still had homes for sale in Flatbush.

Fred Trump went on to erect more than 2,000 homes in Brooklyn between 1935 and 1942. Like Greve, Calder, and the long-forgotten scores of small builders before him, Trump helped weave much of the fabric of outer-borough New York City, creating a vast tapestry of bedroom communities far from the centers of commerce and industry. Here were the homes of the great multitude that flocked to Brooklyn all through the interwar years. The decade between 1920 and 1930, the very years of the tax holiday legislation, was the most rapid period of growth in Brooklyn history.

The borough’s population soared by 577,598 people in those years—more than Washington, New Orleans, or Kansas City at the time. As with Levittown a generation later, the cognoscenti had great fun mocking the mock-Tudor home-scapes of Brooklyn and Queens. George Bowling—protagonist in George Orwell’s Coming Up for Air (1939)—could well have been returning to once-rural Flatlands when he cringed at the “houses, houses everywhere, little raw red houses . . . semi-detached torture-chambers where the poor little five-to-ten pound-a-weekers quake and shiver . . . with the boss twisting his tail and the wife riding him like the nightmare and the kids sucking his blood like leeches.”

Fred Trump helped weave much of the fabric of outer-borough New York City, creating a vast tapestry of bedroom communities far from the centers of commerce and industry.

Critics rightly questioned the suitability of an Old World style like the Tudor for an age of airplanes and penicillin. As Russell Whitehead put it, the Tudor was just “a delicious piece of stage scenery,” no different from “the peasant village Marie Antoinette caused to be erected in the Trianon Gardens.” Lewis Mumford fretted that whenever “a sophisticated age attempts to reproduce the forms of a simple one . . . the result is bound to be ephemeral.”

But Mumford was wrong; if anything the Tudorvilles of outwash Brooklyn have endured, still affordable and remarkably resistant to all but the most egregious lapses of homeowner taste: stainless-steel railings in place of wrought iron; peach-pink stucco slapped atop perfectly good brick; corrugated awnings from the 1970s, now blackened with mold; black-steel casement windows torn out for cheap double-hung, double-paned vinyl replacements. However inept, these are yet marks of a place suffused with the funk and pulse of life unmediated by the pieties of Historical Significance, far from the Midas of gentrification, undiscovered by the merchants of twee.

__________________________________

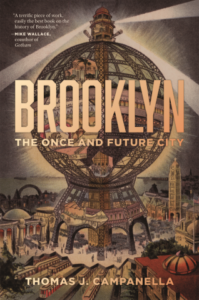

Excerpted from Brooklyn: The Once and Future City by Thomas J. Campanella. Copyright © 2019 by Thomas J. Campanella. Published by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

Thomas J. Campanella

Thomas J. Campanella is associate professor of urban studies and city planning at Cornell University and historian-in-residence of the New York City Parks Department. His books include Republic of Shade and The Concrete Dragon, and his writing has appeared in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. He divides his time between Ithaca and the Marine Park neighborhood of Brooklyn where he grew up. Twitter @builtbrooklyn