“To Secure Democracy You Have To Be Ready to Fight For It Relentlessly.” Readings To Inspire Democratic Struggle

David E. Hoffman Recommends Larry Diamond, Timothy Snyder, And More

What does it take to fight for democracy against a totalitarian state? How does a single person stand up and confront a dictator? What is required to mobilize people by the tens of thousands or millions to demand their rights? How does one find and exploit cracks in the wall of tyranny? These questions are being asked urgently today in battles for democracy around the world.

They are being asked in Burma, where a nascent democracy was destroyed by a military coup; in Ukraine, a young democracy threatened with destruction by Russia; in Belarus, where a proper presidential election was stolen by the ruling despot; in Hong Kong, once a paragon of freedom in Asia, now made subservient to China’s authoritarian rule; and in Russia, where the democratic opposition has been crushed.

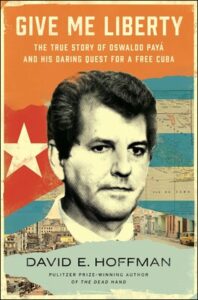

A lone man’s quest for democracy is at the heart of my book, Give Me Liberty: The True Story of Oswaldo Payá and his Daring Quest for a Free Cuba. The biography examines the life and legacy of Payá, who devoted decades to opposing Fidel Castro’s dictatorship. He was in the league of Václav Havel and Andrei Sakharov in his commitment to the principles of a free people and an open society.

But Payá did not know, at first, how to attain them. In fact, he spent years in trial and error, attempting to figure out the best way to reach Cubans and mobilize them. He had no access to radio or television or newspapers, nor the power of today’s digital networks. He simply had to go door to door, person to person. He patiently and earnestly explained to Cubans that they had a right to basic rights. His bedrock belief was that the rights of every person are bestowed by God, not by Fidel.

As a teenager he had protested the crushing of the Prague Spring with Soviet tanks in 1968 and was sent to Castro’s forced labor camps. Later, as a member of the Catholic laity, Oswaldo urged church to leaders stand up for human rights, but weakened by decades of repression, they were more interested in reconciliation than confrontation. Oswaldo could not remain silent. With several friends, he began to publish a leaflet, Pueblo de Dios, brimming with his ideas and commitment to truth and freedom.

He knew of a long-overlooked provision of Cuba’s constitution under which citizens could initiate legislation through a petition that would require 10,000 signatures. By the 1990s, when the collapse of the Soviet Union plunged Cuba into economic despair, Oswaldo decided to use the laws of the state against itself. The provision for 10,000 signatures became his tool. However, not everything worked out properly at first. When he started collecting signatures at his Havana home, a pro-government crowd barged in, ransacked the house and sprayed graffiti on the walls outside: “Payá, you worm,” “CIA agent,” and “Long live Fidel.”

Oswaldo picked himself up and started anew. He wrote a detailed, 46-page “transition program” to describe the path to democracy. But it was too complex. In 1995, he joined others in forming a civil society umbrella group, Concilio Cubano. Castro’s state security arrested the leaders and shut it down.

Finally, Oswaldo came up with a simple, direct approach, the Varela Project, with five demands for liberty. Astonishingly, over several years, at least 35,000 people signed, with names, addresses and identification numbers. They stood up to be counted.

For his effort, Payá was often in the crosshairs of Cuba’s secret police. Seventy-five independent journalists and activists, including those who had worked with him were arrested and imprisoned in 2003 during the “Black Spring.” Many of them were given long prison sentences for nothing more than collecting signatures for the Varela Project.

Payá left an important legacy: he taught Cubans not to be afraid. When mass demonstrations broke out on the island July 11, 2021, many raised their hands in the “L” for Liberación that was a sign of Oswaldo’s movement.

He knew his work was risky. He repeatedly received death threats. He once confided to a friend, “I see very few chances of getting out alive.” He was killed in a suspicious car wreck on July 22, 2012, that has never been satisfactorily investigated.

Oswaldo Payá showed that a single, determined voice can inspire change, even in a totalitarian system. He never lived in a state of liberty, but liberty lived in his mind. As a commentator in Ukraine put it recently, to secure democracy you have to be ready to fight for it relentlessly, with bare hands if necessary.

*

Larry Diamond, Ill Winds: Saving Democracy from Russian Rage, Chinese Ambition and American Complacency

(New York: Penguin, 2019)

Diamond, of Stanford University, understands democracy with alacrity and explains it with eloquence. His 1994 article on civil society for the Journal of Democracy is a classic and touchstone for anyone attempting to grasp the vital relationship between the ruler and the ruled. In this book, Diamond pulls back the camera and provides a sweeping view of the threats to American democracy, including from within the United States. Every page of Diamond’s work offers lessons about democracy and how to fight for it. “Without constitutional constraints on power, there is only a republic of fear,” he writes “What saves citizens from the knock on the door in the dead of night, from the risk of being silenced or removed, is a constitution, a robust body of laws, an independent judiciary to enforce them, and a culture that insists on free elections, human rights, and human dignity.”

Timothy Snyder, The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America

(New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2018)

Snyder, a Yale history professor, comes at democracy through an extraordinary understanding of history, especially the bloodied peoples of Europe in the 20th century. A strength of this book is the clear and absorbing narrative about Ukraine and the assault from Russia that began in 2014—essential context for the war underway today. The Ukrainians thought of themselves as different from Russia; they had mastered essentials of being a democratic state, he writes, including regular elections, and the right to peaceful assembly. “In a country that had seen more violence in the 20th century than any other, the civic peace of the 21st was a proud achievement.” That achievement is now at serious risk from the Russian onslaught.

Frank Dikötter, How to Be a Dictator: The Cult of Personality in the Twentieth Century

(New York: Bloomsbury, 2019)

Dikötter, a historian of China at the University of Hong Kong, brilliantly sees despots for what they are and what techniques they use, making this book extremely informative for those who seek to oppose dictatorship. His core insight is that dictators create a cult of personality in order to hang onto their illegitimate power. “Naked power has an expiry date,” he writes. “Power seized through violence must be maintained by violence… A dictator must rely on military forces, a secret police, a praetorian guard, spies, informants, interrogators, torturers. But it is best to pretend that coercion is actually consent… Throughout the 20th century hundreds of millions of people cheered their own dictators, even as they were herded down the road to serfdom. Across large swathes of the planet, the face of a dictator appeared on hoardings and buildings, with portraits in every school, office and factory.”

Jan Karski, Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World

(Penguin Classics, 2012, first published by Houghton Mifflin in 1944)

For a story of sheer courage and a demonstration of how one person can make a difference, this memoir of a Polish underground resistance fighter during World War II has no parallel. Karski witnessed a Nazi extermination camp, dressed as an Estonian guard, and managed to warn the world of the horrors. “We passed through a small grove of decrepit-looking trees and emerged directly in front of the loud, sobbing, reeking camp of death.” He added, “The chaos, the squalor, the hideousness of it all was simply indescribable.”

Carl J. Friedrich and Zbigniew K. Brzezinski, Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy

(originally published by Harvard University Press in 1956; reprint by Frederick A. Praeger, 1966.)

This is a classic worth returning to again and again. Writing in the early years of the Cold War, the authors created a text that stands the test of time. They showed that totalitarian dictatorships share common characteristics: “an ideology, a single party typically led by one man, a terroristic police, a communications monopoly, a weapons monopoly, and a centrally-directed economy.” This insight—and many others throughout the book—are equally as valid today as they were in the 1950s. Especially powerful and timeless are their chapters on totalitarian propaganda and secret police forces.

__________________________________

Give Me Liberty: The True Story of Oswaldo Payá and his Daring Quest for a Free Cuba by David E. Hoffman is available from Simon & Schuster.

David E. Hoffman

David E. Hoffman is a contributing editor and member of the editorial board of The Washington Post. He was previously assistant managing editor, foreign editor, Jerusalem correspondent, Moscow bureau chief, and White House correspondent for the newspaper. He is the author of The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy, which won the Pulitzer Prize, The Billion Dollar Spy: A True Story of Cold War Espionage and Betrayal, a New York Times bestseller, and The Oligarchs: Wealth and Power in the New Russia. He lives with his wife in Maryland.