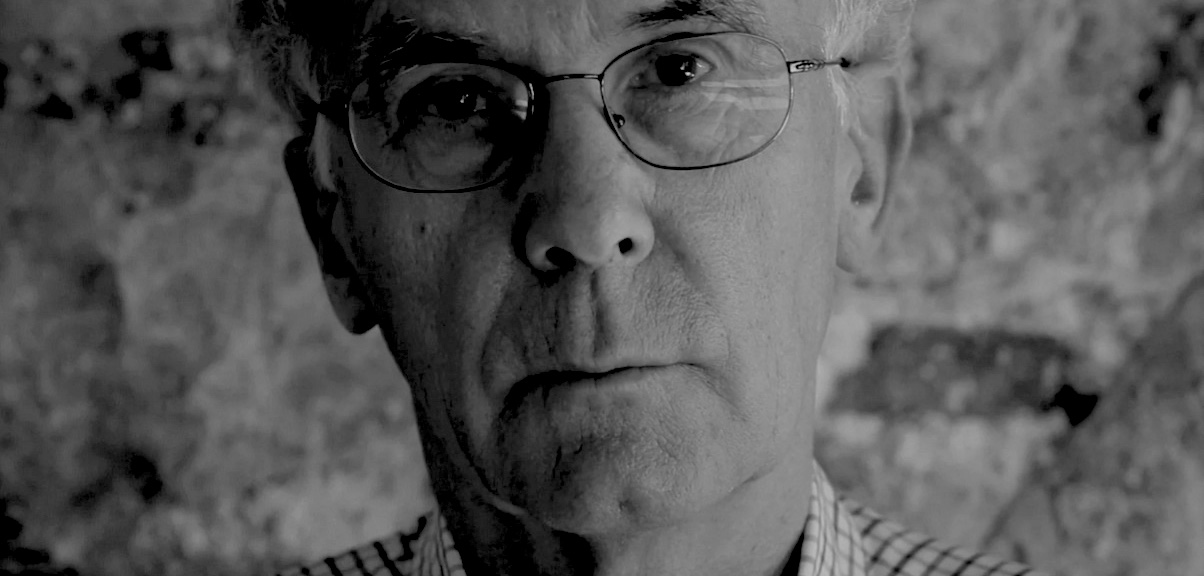

“To Become a Poet is to Step Into the Void.” Brian Henry on Slovenian Poet Tomaž Šalamun

With Poems Translated by Brian Henry

“To become a poet is to step into the void, to jump into the dark.” Born in Zagreb on July 4, 1941, Tomaž Šalamun grew up in Koper, a seaside town near Trieste, Italy that became part of Yugoslavia after World War I. Because of his father’s political difficulties with the Communist regime, his family moved around for several years, eventually settling in Koper. Šalamun has said, “What really defines me, basically, is that I grew up on the border between two worlds in the Cold War,” and he has described his “background” as “very, very chaotic,” “the result of the terrible history of twentieth century Central Europe,” which he believed “shows in [his] language.”

Šalamun started writing poetry at the age of twenty-two after seeing the Slovenian poet Dane Zajc (1929–2005) give a reading. To him, Zajc “had such a magical presence, an angel jumped out of his shoulders.” Šalamun recalled that his “first five poems came in half an hour, and felt like stones falling from the sky.” After he had written just twenty poems, he was elected editor of the subversive literary journal Perspektive, which, along with his poem “Duma 1964,” led to his arrest. He was told that he’d spend twelve years in prison, but due to international pressure, was released from prison after only five days.

He emerged as a cultural celebrity, which made him feel compelled to write more poems in order to live up to his newfound notoriety. Although free from prison, he was still locked out of mainstream publishing in Yugoslavia, so his first two books—Poker (1966) and The Purpose of a Cloak (1968)—were published in samizdat. Despite an enthusiastic reception in some quarters, Šalamun’s poetry was seen as a threat to the status quo.

The Slovenian poet and playwright Ivo Svetina has written about how Šalamun “desacralized” and shunned “proper, high, literary use” of the language, which led to a “chorus” of voices in Slovenia that “shouted about the danger that comes with Šalamun’s poetry, almost a natural disaster that will topple both the foundations and superstructure of society, both the community of the nation and the basic cell of society, both matter and spirit, both language and literature.” Šalamun was also prohibited stable employment and had to resort to piecemeal work such as selling encyclopedias door to door, translating non-literary texts, and smuggling jewelry from Italy into Yugoslavia.

Šalamun studied art history, as well as history and architecture, at the University of Ljubljana, later becoming a curator and a founding member of the conceptual art group OHO, which took him to the United States for the first time in 1970 as part of an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. He credited his month in New York with changing his life because it turned his attention toward American culture.

That connection was further strengthened two years later when he returned to North America as a guest of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa, which led to two chapbooks in English translation: Turbines (1973) and Snow (1974). Šalamun has said that spending so much time in the United States and being away from Slovenia were essential to his growth as a poet, in part because (according to Slovenian poet and art historian Miklavž Komelj) he “always needed immense spaces; not only transoceanic and intercontinental distances, but intergalactic. And interlingual.”

Because of political difficulties in Yugoslavia, Šalamun could not return to the United States for a few years, and another collection in English translation would not appear until 1988, when Charles Simic edited a volume of Šalamun’s selected poems for Ecco (Simic also translated many of the poems in the book, using Serbian translations of the Slovenian poems). In a 2008 conversation with Simic, Šalamun said, “I was fighting to be free within my writing. And just this was subversive, and therefore political….The really bad years were the mid-’70s….Coming back from America, from Iowa in 1973, I was annihilated. I couldn’t make any money.”

Still, Šalamun felt that it was “vital to be free in the language” despite the political situation in Yugoslavia at the time. For him, poetry “participates in and is part of a tower that is five thousand years old and that has built-in instincts…for freedom.” The Slovenian art historian Tomaž Brejc has discussed how Šalamun’s urge to leave “the tribe” allowed him to “see better,” to “examine history, the nation’s essence and its current pulse,” and to “introduce an international language” into Slovenia.

As a result, Šalamun “created a paradigm of an open, polyglot life for Slovenes in this century, a skillfully moving subject who changes languages like changing planes and taxis, newspapers and encyclopedias, money and messages.” In a review of the 1988 Selected Poems, the Slovenian poet and cultural critic Aleš Debeljak (1961–2016) wrote that Šalamun never seemed “squarely integrated into the Slovene paradigm” mainly because of “his unrestricted and forceful desire always to be already somewhere else—moving through the past and the present, traversing the many different vocabularies and strange provinces of the mind and geography, always on the go.”

Nevertheless, Debeljak claims, Šalamun “single-handedly changed the course of Slovene literature…balancing the cosmopolitan sensibility and persistent Slovene obsession with its precarious cultural position of being squeezed between two major cultures, Italian and German.” From the 1980s until shortly before his death in 2014, Šalamun was a frequent visitor to the United States: he was a Fulbright Scholar in New York in 1986, the Cultural Attaché for the Slovenian Embassy in New York in the late 1990s, and a visiting professor at numerous universities.

In addition to revolutionizing Slovenian literature, Šalamun has inspired several generations of poets from around the world. According to Brejc, Šalamun’s poems are “above all large windows, fields of freedom for a new, direct perspective on words” that “initiated a great social liberation of language.” Komelj has explained how this liberation also extended to the political sphere, as Šalamun’s commitment to total freedom in his poetry, including its open expressions of homosexual desire, “demanded a different mental climate” and “irreversibly changed the entire [Slovenian] space on all levels. For example: [Slovenian writer and lesbian activist] Nataša Velikonja can accurately cite his liberating poetry as one of the “the foundations on which gay and lesbian activism was formed in the mid-1980s” in Slovenia.

Šalamun mostly wrote early in the morning or in the middle of the night when a poem would awaken him. Remarkably prolific, he published fifty-two individual collections of poetry, fifteen of them between 1971 and 1981. And in the last decade of his life, he wrote twenty books, nine of which were published after his death. His one dry spell was in the early 1990s, when a personal crisis and the wars in the Balkans rendered him silent and “afraid of poetry”:

God can crush you, if you, as I do with language, try to reach the borders of everything possible, the borders of language, to go to total transgression, to go to total blasphemy….It was as if God took everything out of me, it was as if my head would explode, as if my brain would melt, and I was left in a completely dark, cold place, in total terror and feeling guilty and not being able to help myself, and I was not able to write for four and a half years after this happened to me.

Although the wars weighed heavily on him, he largely blamed himself for this silent period: “I’m constantly escaping God, quarreling with Him, and making terrible gestures, terrible blasphemies. I’m a cannibal against God, sometimes, and still I’m crushed in total humility.” This tension, though, was usually productive for his poetry. Komelj has described how Šalamun “constantly moved in the realm of dreams and twilight, and knew that true existential freedom involves a confrontation with the monstrous.”

In interviews, Šalamun has compared writing poetry to “religious delirium” because of its “intensity of delight and the feeling of something I don’t understand that is deep, that regenerates me and also horrifies me,” while also divulging that “writing is a total joy…a dance, an opening up, a standing and taking in of light, total delight”: “I love the extremes….I like to experience the utmost borders of sanity, to test my courage, then try to come back and still, in some gentle way, to expose myself to the most extreme dangers…[t]o increase the human experience.”

–Brian Henry

*

Where Is North, Where Is South

the first discovery speaks of the randomness of the world

the second discovery speaks of the precondition

the third discovery speaks of insinuating with the head

the fourth discovery speaks of a briefcase

the fifth discovery speaks of a method of distinction

I.

there are six lines on the wall

a convex edge in the corner

half a meter lower says Adelshoffen

on the left and right you can see a windowpane with iron trim that’s

painted with minium

II.

all the northern countries are north of me

all the southern countries are south of me

III.

often it happens that I insinuate with my head

IV.

the first definition of a briefcase pushes the briefcase

the second definition of a briefcase pushes the briefcase

the third definition of a briefcase pushes the briefcase

V.

I produced the word petaheva

I produced the word petaheva again

as we distinguish a lizard from a lizard

so we also distinguish the first product from the second

Blue

healers / flat sky / flame

gifts for the hill / dachshunds

blue cellophane / blue color of bread

blue white walls / dante

blood blue / outstretched wings blue

a terrible guardian angel protects maruška

blue kristof / semen blue / we’ll die on the same day

blue enemies / tall blue figure

friends / we walk on the red sea blue / the scent of hay

ash / the world’s end / blue delight

fairy tales and conjurers / flying over the coast

blue mouth / day / juice / boats

blue white ships / maria’s messengers

blue karst / blue love / blue plains and body

use / blue wheat / speed / growth blue

light / buildings / blue shepherds and sailors

robbers / cobblers blue

blue foundations / blue storms / blue sand / breathing

blue face / crosses nailed to the wall

terrible blue mooing of an animal / earth / blue manhattan

good ripe fruit measured out by people

blue game / mountains / blue snow / sheep / machines

offerings / blue murder / yearning / dogs in the suburbs / money

blue jeans and prayers / women in markets / children

passion blue / grace / skin blue / silent blue rainbow

blessed sleep and words

blue light

blue day

blue fuck

blessed light / blue maruška / my wife

Ether

I.

My hands are tied with a rope, at the ends

there’s wood. The sky is violet and brown.

When I see this, it doesn’t touch me.

I feel the fingers on both hands.

I hear a car passing by.

Wool sips me. I’m a lamb.

A lot of salt is in the air, the mistral is blowing.

Semicircular arches are being made from the light,

like a wide rainbow, from me. I no longer have

any weight and maybe this will lift me up.

Then I won’t write anymore. I grease,

weigh down my body so I can write.

I see only the first three circles. I cannot

look further up because of

the melting. It disperses, no longer visible.

The word is a weapon that protects me from

the path. Now I’m not a lamb, I have

a hand, I caress the grass. In my ears I have

the feeling that I’ve been in the sea

a long time. I’m thinking. I see a house.

Accounts of this are a defense against

annihilation.

II.

Geniuses and angels slide out of people’s

noses. At first they’re like

embryos, then like pupae opening

their fibers. I lean over for a cigarette.

I clench my teeth and clutch my knees

with my palms. The lord of desire is

blue, not monolithic. In the east they

highly valued silk because it resembles

this air. I have no defense.

from The Purpose of a Cloak (1968).

9 3

I’m placed in safe hands. I want

to be hungry so that this ends.

On the horizon, a black dog swims

as if there were water, but there’s no water.

It chews my hand, but it doesn’t hurt.

The black dog is quite mellow. I’m artificially

creating fear. Fear is a work of art.

I’m vicious. I pour a pail of water

over my head. All this has no

taste, the colors have their

locus, their origins. They

populate my body like ether.

III.

Sometimes cobwebs are on words.

Sometimes filaments, sometimes salt.

Now there’s bark and knots and a screeching

knife. I always go clothed here,

not naked. I imagine that I

know how much it can puff in my head.

I really have no idea. Sometimes I throw

the knife into the veil so that I can get it

back. Under the skin is a second skin,

under the second skin is a third skin.

I see the end of the street. I can count

everything: two candelabra. I see

a grid made from the lattice of Sol LeWitt.

IV.

The curves drive me to sleep,

a child dies.

On the altar there’s eggnog,

I’ll stay, I’ll stop.

God, grant me rest,

in the cave,

in the rain.

______________________________

Kiss the Eyes of Peace by Tomaž Šalamun in translation by Brian Henry and with a foreword by Ilya Kaminsky is available via Milkweed Editions.