Time and Materials: On the Art of the Experimental Memoir

John West Considers the Literary Fragment

1.

The conceit of a memoir is that the important parts are all mostly there, and the unimportant parts are all mostly left out. But since memoirs can’t write into the future, I can’t bring myself to trust them.

In a story, there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end: a chain of cause and effect that propels its characters from beat to beat. In a life (at least in mine), cause and effect loop back in on each other, and as the future becomes the present, it casts new light on the past. You can’t write a memoir after you’ve died, so there is always a new story that could be told, a different, perhaps truer, way of understanding your past.

Absent some ordering structure, facts are boring. What makes them interesting is the way they bounce off their neighbors and create a context into which we can make meaning. When an author chooses which facts to include and which to elide, they are creating a story that is incompatible with the other stories they could have told, had they picked different facts. This means that the best a memoir offers is verisimilitude, something like the truth, but never—no, not ever—the real story of what happened.

So, I don’t trust memoir, but I did write one.

Seven years after I started, I finished Lessons and Carols, a memoir about ritual, addiction, and other people’s art. At some point along the way, I managed to broker an uneasy peace with the form: I’d write a memoir, but only if it were fragmented, and only if it weren’t linear. I wanted it to be fragmented because I didn’t want to allow me or my future readers to be swept up by the verisimilitude and mistake it for reality; I wanted them to know I was eliding. I chose nonlinearity because I wanted to respect the way life—messy and shifting—ignores time, wanders back through memory and reaches out into the future.

As the future becomes the present, it casts new light on the past.

Writers mostly write in what I call normal prose. We string words into sentences that are neither too short nor too long. We set sentences into paragraphs that are neither too sparse nor too florid. These paragraphs, taken together, offer cause and effect, moving from past to present, from origin to endpoint, unlocking new understanding as the sections accumulate. It is the very fact that memoir is written in normal prose that lulls us into a false belief about their comprehensiveness and veracity.

I think it’s easier to see the effect of abnormal prose—the way, for example, fragments or nonlinearity make a text work in new and strange ways—but there is nothing neutral about normal prose; it, too, has its effects. A form always sets expectations. Sometimes those expectations are fulfilled. Sometimes they are subverted. Either way, form shapes what readers understand the story to be. The choice of form, the choice to work with or against: these have deep aesthetic, and thus deep moral, consequences. This is even true (and maybe especially true) in forms that don’t feel like a choice at all, by which I mean prose of the sort that tries to fade into the background—by the normal prose in which so many memoirs are written.

2.

Lessons and Carols is built from 163 present-tense fragments, a couple only a sentence long, a few stretching for several pages, most somewhere in between. Each fragment is constructed from a blend of materials. 65 of them contain a quotation from another book. 79 of them contain one of my motifs—like blackberries or birds, to name a couple. 26 of them are written around the theme of parenthood. 78 around addiction and mental health. 38 around loss. And 21 are written around my yearly heterodox reenactments of the Episcopalian Christmas tradition called the Nine Lessons and Carols.

The fragments span two decades, and they don’t follow IRL chronology. But in the absence of time, a book needs something else to order its narrative. In Bluets, for example, Maggie Nelson offers a philosophical almost-argument about the color blue, and she hangs the narrative off of it like clothes on a line. In Her 37th Year, an Index, Suzanne Scanlon uses the alphabet to order her narrative. In The Body: an Essay, Jenny Boully works with footnotes to an erased essay, and this essay—though it is literally hidden from the reader—structures the movement of her fragments. We are living in a moment when fragmentary books that don’t choose chronology are flourishing, and the possibilities seem endless.

Of course, form always drives its book forward. In these books, their unusual forms are impossible to miss. But in books written in normal prose, the form is also pushing the plot along; it’s just we’re more accustomed to seeing these kinds of stories, so we might miss the work the form is doing altogether.

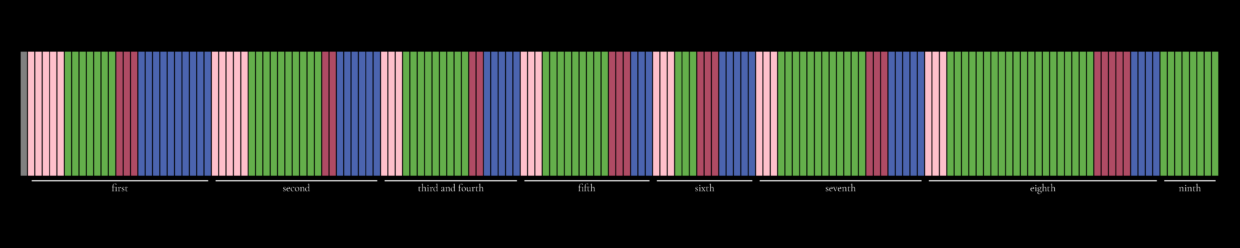

I ordered my fragments into a series of “lessons and carols,” more-or-less mirroring the Episcopalian service of the same name that tells the Christmas story (though I merged the third and fourth lessons in mine). Each lesson cycles through my main themes—parenthood, addiction and mental health, ritual, and loss—building on itself, I hope, in the same way the liturgy does. Just as in the Episcopalian service, where the ninth lesson breaks out of narrative entirely, and recounts the opening of the Gospel of John (“In the beginning was the Word,” etc.), my final lesson, too, breaks with the cyclical form. Here you can see parenthood, addiction and mental health, ritual, and loss as they weave together.

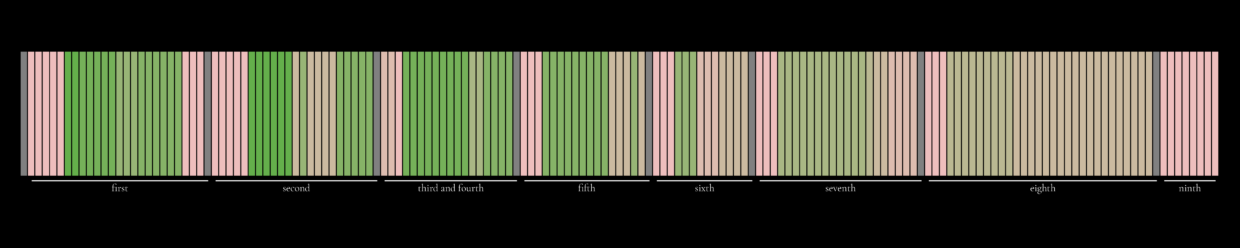

In order to see the structure of a book written with an atypical form in my mind’s eye, I created a series of increasingly complicated spreadsheets as I wrote. Each row corresponded to a fragment, and I marked which themes and motifs were operative, and whose work I was referencing. Most importantly for me, I noted when in real time each fragment occurred. Here, you can see each fragment and how they moved from the past to the present.

If you squint, you can see that time still moves forward, albeit with a few stumbles. It turns out that I wasn’t quite as successful in shedding chronology as I set out to be. But I like to believe that linearity has been left, mostly, on the sideline, that other ways of thinking about time have taken the field.

3.

When they don’t know how to properly gauge the scope of a project, a good contractor works on time and materials. A book is no different, really. So far I’ve been mostly discussing time, but materials matter, too.

Bluets pairs Wittgensteinian propositions (form) with a narrative of suffering and love’s limitations (substance). T Fleichmann’s Time is the Thing a Body Moves Through works ekphrasis (form) together with themes of rejuvenation, gender, and sex (substance). Both books advance by shifting the meaning of their themes and motifs. Blue takes on new and different connotations as Nelson writes, just as the artwork Fleischmann describes takes on new associations as the essay unfolds. But is this really so different than the plot of a traditional book, when time’s movement causes characters to change?

The interplay of time and materials: this is how any book gets built. In early drafts, the bird motif recurred whenever I felt like it. In later drafts, through careful spreadsheeting, I tried to move the “plot” of my book forward by changing how those birds were understood. You can see this yourself in this chart. Notice how birds are introduced in the parenthood theme, cycle through a few others, and end in the addiction and mental health theme. I tried, in each fragment in which they appeared to advance the understanding of what they meant.

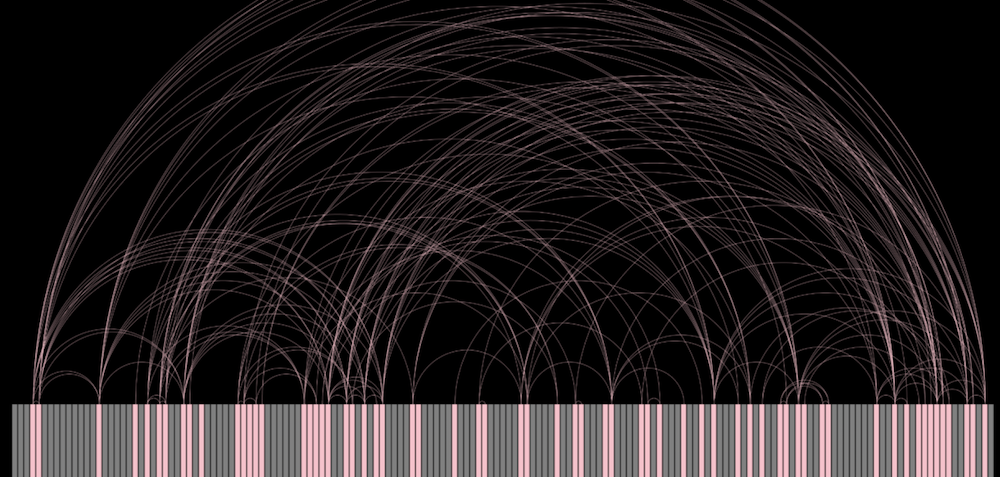

Another example. I quote others’ writing a great deal in my book. But just as with my motifs, I wanted these references to advance my narrative. So each citation recurs at least once. And you can see here how they create a web of moving parts that—I hope anyway—push the reader forward from fragment to fragment.

Another example. I quote others’ writing a great deal in my book. But just as with my motifs, I wanted these references to advance my narrative. So each citation recurs at least once. And you can see here how they create a web of moving parts that—I hope anyway—push the reader forward from fragment to fragment.

Lauren Oyler, in her novel Fake Accounts, has her protagonist muse on fragmentary work: “What’s amazing about this structure is that you can just dump any material you have in here and leave it up to the reader to connect it to the rest of the work.” I don’t want to ascribe the belief that fragments are cheap to Oyler herself, but I do think this is a common conception of the books I’ve highlighted (and the one I’ve written): they are at once too easy and too pretentious.

Lauren Oyler, in her novel Fake Accounts, has her protagonist muse on fragmentary work: “What’s amazing about this structure is that you can just dump any material you have in here and leave it up to the reader to connect it to the rest of the work.” I don’t want to ascribe the belief that fragments are cheap to Oyler herself, but I do think this is a common conception of the books I’ve highlighted (and the one I’ve written): they are at once too easy and too pretentious.

I offer my spreadsheets as evidence that there’s nothing easy about fragments. As for the charge of pretension, I would agree that there’s pretense involved in non-obvious forms, but there’s pretense involved in any form. In the words of RuPaul, “We’re all born naked and the rest is drag.” That is, there is not a “natural” way for language to be arranged. We’re all born formless and the rest is pretense.

4.

In the Robert Hass poem that gave this essay its name, he writes about his speaker’s desire “To render time and stand outside / The horizontal rush of it, for a moment.” In writing my book the way I did, I, too, wanted to stand outside time, precisely because the future is unknowable and because the experiences I describe collapse the past and future into a kind of expansive present-ness: It’s the tug to parent the way I was raised (or parent in opposition to the way I was raised). It’s the way old behaviors lead to the same behaviors (or to new ones). It’s the way ritual binds us to the past and stretches out into the future. It’s the fact of loss—the way it refuses to let the past stay behind us.

In the end, form, like life, is full of choices.

“We aren’t what we were till we become what we will be,” I write in my book. That’s why I didn’t want to write a traditional memoir. Not because the form is bad, but because the form doesn’t capture what is essential about my own experience. I wrote in a form readers couldn’t ignore to jolt them out of normal prose so that they might see life I see it.

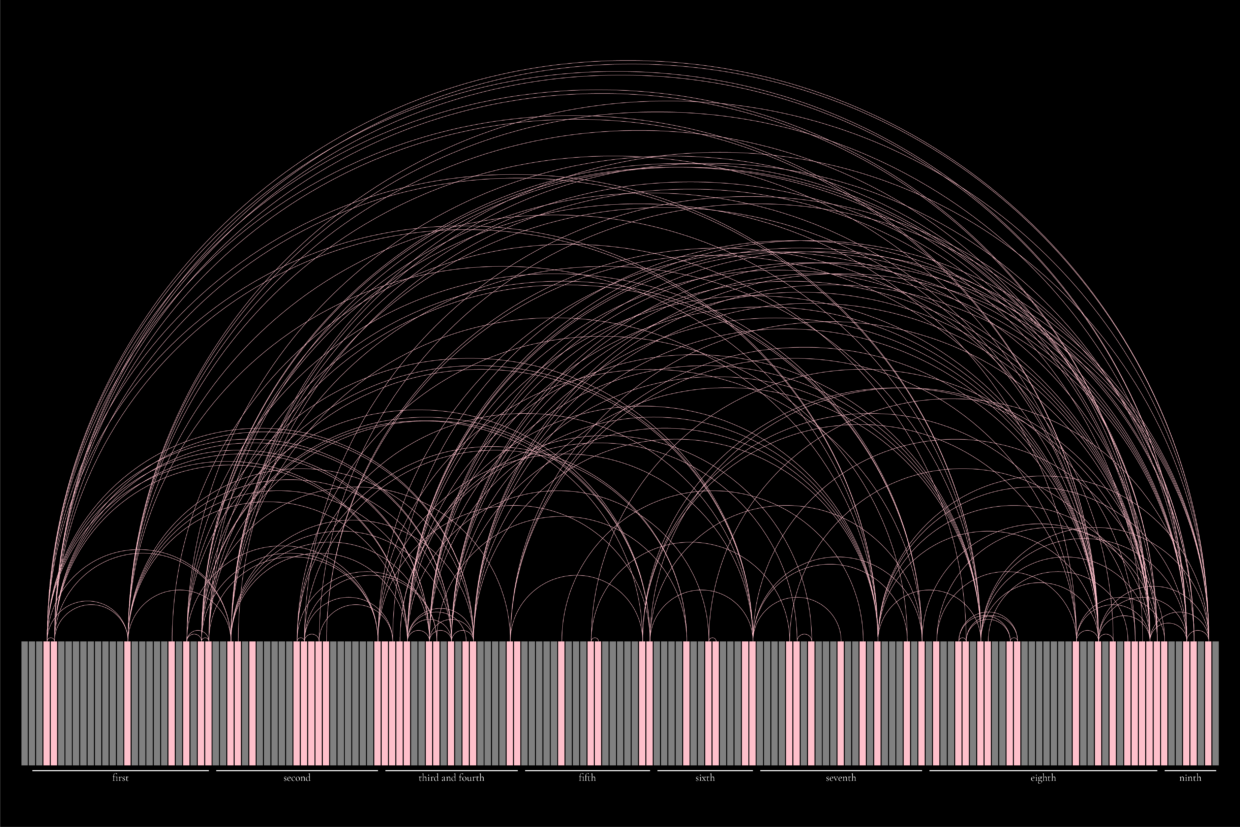

One last chart. Here, I’ve clustered the fragments so that those with similar themes, motifs, and references are pulled near to each other, and those with dissimilar themes, motifs, and references are pushed apart.

I wanted my book to feel like this because this is how my life feels: full of structure and meaning and order, but graspable only if you give up on the idea that things move from beginning to middle to end tidily. Because, in the end, form, like life, is full of choices. Make the important ones with intention.

__________________________________

Lessons and Carols: A Meditation on Recovery by John West is available from William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

John West

John West is a technologist and writer, currently reporting the news with code at the Wall Street Journal, where his work has won multiple awards and been a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize. Previously, he worked at the MIT Media Lab and the digital publication Quartz. He holds an MFA in writing from the Bennington Writing Seminars and degrees in philosophy and music performance from Oberlin College. He lives in Boston with his partner, their daughter, and a cat.