Tight Breeches and Loose Gowns: Going Deep on the Fashion of Jane Austen

Hilary Davidson Takes Us Through Regency Style

The early 19th century in Britain can be slippery to characterize. The 18th century springs into being in history books with robust Enlightenment vigor. After the Revolutionary period, 1775–93, the Western world changed. How do we define the particularity of this time, where the end of the “long” 18th century blurs into the beginning of the “long” 19th century? Regency people are Georgians, but are they also proto-Victorians? Might they be Romantics or Classicists? The temporal definition remains the Prince of Wales’s Regency, 1811–20, which coincides with Austen’s publication period of 1811-17. The Regency is a flexible concept, a summary of the early 19th century sometimes starting at the French Revolution, sometimes finishing at Victoria’s accession in 1837—a transitional period that redefined clothing norms and shaped the 19th-century world. For clothing I define my “long Regency” as 1795 to c. 1825—from when waistlines began to rise until soon after the Regent became George IV. Henceforth, “Regency” refers to this rough quarter century unless otherwise specified.

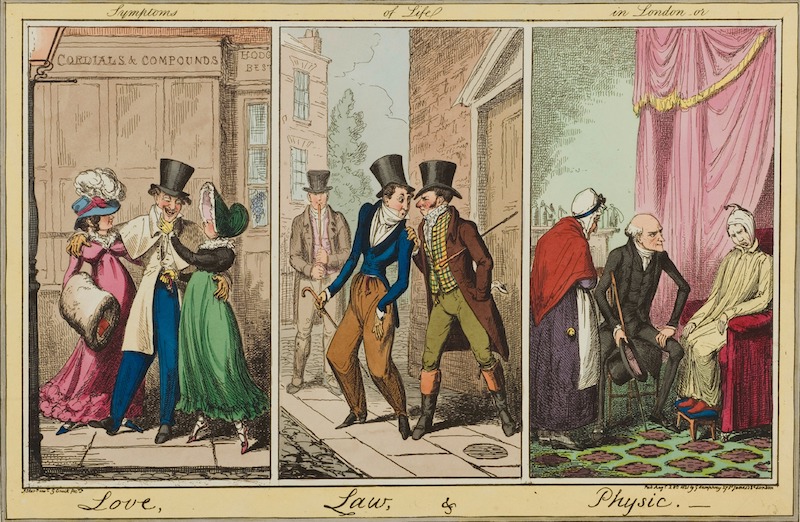

The Regency is defined by strong clothing narratives. The French embraced Anglomania, waistlines rose and dresses turned white and flimsy, ornamented with fripperies borrowed from other times and cultures. Women’s heads retreated into bonnets; their bosoms were newly defined and uplifted. Men transformed Classicism into a focus on the athletic body. Their muscular thighs sprang into pale, defined relief by contrast with their broad, wool-clad shoulders. Disrupted from the Continent by war and blockade, British fashion embraced French style, after Napoleon’s final defeat in 1815, to succumb to a new tide of romantic influence, before George III obligingly departed and turned the Prince of Wales into George IV.

Several long-lasting, major clothing changes emerged. Trousers replaced knee-breeches in the male wardrobe. Women’s stays retreated into underwear, never seen again in respectable society. Front-opening gowns, established for a century, became back-opening gowns. Cotton overtook linen as the plain fabric of choice. Embellished display disappeared from male dress, replaced by sombre surfaces emphasizing the lines of good tailoring. British-manufactured textiles finally started surpassing desirable imported Asian cloths such as muslin, and made cheaper dress accessories more readily available to ordinary consumers.

Like many fashion histories, this work emphasizes the clothing of the middling and upper classes, “partly because the dress of the middle classes reflects one of the most influential elements of British society at the time,” but also because Jane Austen’s life and works sit so neatly there. Upper-echelon clothing has received a disproportionate amount of attention as the Regency’s aesthetic bastion and aspirational destination, although recent scholarship on dress of the lower sorts is changing this. While my discussion ranges from court to courtyard, its attention is closest at the genteel center, the middling sorts and upper gentry, who owned land or were engaged in professional trades. It also concerns the people who lived and worked with them, the aristocracy they looked up to, and the laborers supporting their lifestyles. Austen gives us an excellent entrée into the complexity and social implications of gentry clothing systems of her time.

An 1824 review praised Austen’s skill in envisioning “the inmates of the cottage, the farm-house, the manse, the mansion-house, and the castle [and] my lady’s saloon too,” “sketches of that sober, orderly, small-town parsonage, sort of society in which she herself had spent her life.” She was born the seventh child and second daughter of Cassandra Austen (née Leigh, 1739-1827) in the parsonage at Steventon, Hampshire, in 1775, where her father, the Reverend George Austen (1731-1805), had the living. Her brothers were James (1765-1819), George (1766-1838), Edward (1767-1852), Henry (1771-1850), Francis (“Frank,” 1774-1865), and Charles, who followed her (1779-1852).

Jane was devoted to her older sister Cassandra (1773-1845) from childhood, and the pair were unusually close, especially after Cassandra’s fiancé died in 1797. Neither ever married. From her early teens, Austen entertained her literate, lively family with hilarious short fiction and boisterous histories, now collected as the Juvenilia (1787-93). She began drafts of some of her later published novels in the late 1790s.

In 1800 George Austen retired and moved his womenfolk to Bath, where they lived until his unexpected death in 1805. Austen began The Watsons there c.1 804 but never completed it. Mrs. Austen and the girls moved around, living in rented accommodation and then with Frank’s family in Southampton until, in 1809, Edward—who had been adopted by wealthy childless cousins and took their surname Knight in 1812—offered his relatives Chawton Cottage, part of his Hampshire estate. Austen lived the rest of her life there until her death from a long (and unidentified) illness in July 1817, aged 41.

Four novels were published (anonymously) in her lifetime: Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814) and Emma (1815). Persuasion was published posthumously in 1817, in a set with a revised version of her first completed novel, now called Northanger Abbey, and a note revealing her authorship. Austen drafted the incomplete manuscript now called Sanditon before her death. Of the estimated 3,000 letters she wrote in her lifetime, 161 survive, mostly to Cassandra, plus miscellaneous poems, plans and incidental writings.

The family was never wealthy. The Revd Austen did not save much of his annual income of about £600, and after his death the women relied on small inheritances and financial support from the brothers to survive, meaning that the sisters were always careful about money, and small sums mattered. Earnings from her writing eased Austen’s worries somewhat—notably £140 from Sense and Sensibility—and totaled £684 13s. in her lifetime. She invested much of this to bring her an additional £30 per year. Being of genteel birth, Austen had social constraints on her money, such as charity and paying for letters received. Her budget for 1807 shows that, of her £50 15s. 6d. for the year, more than £4, or roughly a month’s income, was spent on parcels and letters, though the principal expense was £13 19s. 3d. for “Cloathes & Pocket,” vital to maintaining the appearance of her gentility. Of her actual dress, the only known survivals are a pelisse, a shawl, a topaz cross, a turquoise ring, and a turquoise bracelet.

In person, Austen was tall and slender to the point of thinness, with naturally curling brown hair, round pink cheeks and bright eyes. Written references to her appearance have a range of opinions about her attractiveness, but she appears not to have been thought plain. Cassandra painted the only two securely identified portraits of the author: a full-face watercolor the family did not consider a good likeness and a full-length back view of her sitting outside. Other contenders for images of Austen are the Rice portrait in oils on canvas, the Byrne portrait by an anonymous artist, the watercolor from the album of the Revd James Stanier Clarke, and a black paper silhouette. Discussion around these pictures is extensive and often contested.

The traditional critiques applied to Austen’s writing have been that she ignores big history, meaning the charged political situations and theaters of war unfolding all over Europe, summarized by the complaint that “At the height of political and industrial revolution, Miss Austen composes novels almost extra-territorial to history,” although scholars regularly challenge this view. A twenty-first-century critic asserts that Austen “keeps historical reference to a bare minimum,” yet writes two sentences earlier about her descriptions of “volatile social formation as the English landed gentry of the early 19th century interlocked with an acquisitive high bourgeois society”—history references equally important to the emergent 19th century and its dress.

Ironically in an age of growing material consumerism, Austen’s fictional references to dress generally decline as her publications advance. The Watsons (1804-5) and Northanger Abbey (1803) are replete with minutiae of clothing, and discussions of it—a “striking preoccupation with the world of goods,” where later she “learns to pinpoint her characters” possessions more exactly.” Conversely, the fewer details attract greater significance as Austen’s skills improve. When the author mentions an article of clothing or a piece of textile, the reader must pay close attention, as it tells us something about the action or character, helping us to understand her works by exploring the cultural code underlying such specificity. Behind the scenes in the letters, however, Austen despaired of and delighted in the niceties of getting and wearing dress as much as the next person.

Dress in fiction relies on readers’ shared experience of normality, and understanding of social and sartorial conventions.

Dress in fiction relies on readers’ shared experience of normality, and understanding of social and sartorial conventions. The design of garments, and how they look when worn, is nearly always missing from the “’literary mirror’ when held up to nature; it is a pre-existing image assumed by the author to be familiar to the reader.” Therefore, if the text is scrupulously realized, as with Austen, fiction can become a medium for reconstructing clothing. While there is a caution in using fiction as evidence for historical research, Austen is a particularly alert historical writer. Indeed: “Austen as an historian of her time . . . [is] an important but frequently overlooked feature of her practice as a novelist.” The same writer continues:

the novelist’s status as an historical agent is ultimately indivisible from the history in her writing . . . Partly in consequence of the extended interval during which . . . Austen’s narratives gradually became history, reality and temporality are admixed so that Austen’s status as an historian of the everyday turns out to be an unusually precise description of her achievement.

Austen’s contemporary readers recognized this. During her life and immediately afterwards, the reality of her created worlds impressed others who had lived through the same time. “Most Novellists fail & betray themselves in attempting to describe familiar scenes in high Life . . . here it is quite different. Everything is natural, & the situations & incidents are told in a manner which clearly evinces the Writer to belong to the Society whose manners she so ably delineates,” wrote one Austen acquaintance about Mansfield Park. In the year after the novelist’s death, an unknown critic wrote that

Her characters, her incidents, her sentiments are obviously all drawn exclusively from experience . . . she seems to have no other object in view, than simply to paint some of the scenes which she has herself seen, and which every one, indeed, may witness daily . . . She seems to be describing such people as meet together every night, in every respectable house in London . . . Her merit consists altogether in her remarkable talent for observation. . . in recording the customs and manners of commonplace people in the commonplace intercourse of life.

People who read Austen and knew the times she wrote in considered her true to life, natural, accurate and observant—an excellent ground for studying “commonplace,” albeit respectable, dress of her time.

Juliette Wells emphasizes that the more nearly people’s important qualities in representational fiction approach the universal, the better the fiction is judged to be, so clothing, their historically determined appearance, is less relevant. But clothing, perceived by its wearers and observers as part of characters’ identity, creates half the physical self. In fiction as in life, “the dressed body is a fleshy, phenomenological entity that is so much a part of our experience of the social world, so thoroughly embedded within the micro-dynamics of social order, as to be entirely taken for granted.” Presenting how and why people took what for granted in their clothing is the work of dress history, especially as historical bodies are so bound up in our perceptions of their dressed bodies. How Austen’s contemporaries saw people wearing clothes is not the same as how we see them retrospectively.

To the Regency observer in London’s streets a Frenchman stood out immediately, as did an English miss strolling in the Tuileries to Parisians. The dandy seeking perfect fit found it in a tighter jacket than any gentleman now would tolerate, while visible shoulder blades and upper arms could constitute scandalous female nakedness. Throughout, I have sought what was “entirely taken for granted” in dress during Austen’s lifetime and re-read her writings in the context of how she and her audience would have understood the clothed Regency body.

How Austen’s contemporaries saw people wearing clothes is not the same as how we see them retrospectively.

Observations of “the long and continuing battles for the posthumous body of Jane Austen,” played out among her biographers, “continually being torn into parts and put back together again,” are apt for this work. If “whatever had most to do with [Austen’s] bodily life is hardest to track down,” then the clothing of her age’s various imaginary and real bodies has not been paid enough attention in its own context. Even before the spate of 1990s screen adaptations, a 1970 article regretted that “For the public at large, and even . . . for some serious historians . . . the past seems to remain a Never-Never Land in which . . . the heroines of even Jane Austen’s novels are scantily draped in damped muslin.” I question such Regency dress mythologies wherever possible.

The “heritage” Austen relies on presenting Regency fashions as part of the display of period objects authenticating the narrative space. I recognize that in popular culture “Regency England becomes a timeless, mythological place called Austenshire,” dominated by the flickering light of cinema bedazzling audiences with all its “bonnets and carriages and parks and starched pinnies, and Colin Firth and Alan Rickman striding about in ruffled shirts and shiny boots.” The modern bodies of actresses portraying Austen heroines “evoke, through carriage, gestures and attitude, a late 20th-century Western female corporeality” enacting “history as the present in costume” and an assertive physicality appealing to modern viewers. No actor will ever wear his tight jacket and breeches with the unthinking ease of the Regency gentleman, who knew no other clothed experience. The weather requirements of filming costume dramas bias screen audiences towards an endless-summer view of Regency dress, according well with muslins and parasols.

“In any search for Jane Austen,” as Emily Auerbach cautions, “we must break free of dear Aunt Jane . . . We must strip off those ruffles and ringlets added to her portrait, restore the deleted fleas and bad breath to her letters, and meet Jane Austen’s sharp, uncompromising gaze head on.” In dress terms the “ruffles and ringlets” are the fashion-plate, screen idealizations of Regency dress, and the “fleas and bad breath” are prosaic flannel underwear, stockings darned into lumps, and muddy, manure-coated streets. However, filmed Austen can suggest the lived effect of clothes in her lifetime, “of interest . . . as objects of desire in their own right.” If readers, re-enactors, curators, collectors, writers and designers now desire Regency clothing, the screen has shaped their vision.

____________________________

Adapted from Dress in the Age of Jane Austen: Regency Fashion, by Hilary Davidson, published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2019 Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.

Adapted from Dress in the Age of Jane Austen: Regency Fashion, by Hilary Davidson, published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2019 Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.

Hilary Davidson

Hilary Davidson is a dress and textile historian based between Britain and Australia, and an Honorary Associate at the University of Sydney. She has curated, lectured, broadcast and published extensively in her field.