Thriving in Discomfort: SJ Kim on Writing About and Through Displacement

“Writing can reassure and writing can upset, writing can disrupt.”

My partner and I seek out expansive green spaces. He drives just under five miles, pays for parking, and we take long, near-silent walks hand in hand for hours. I have asked my partner to stop kissing my hand, a habit I love, but it feels too dangerous.

These walks soften the edges of the homesickness I am waiting to be named. I feel I would give anything to walk the red dirt of home. I feel I would give anything. I know you know I mean it when I say it is this sickness that is my slow dying. I know you know that the home I am sick for was never, home was never. And, so, home is forever, too. What I mean is, once I wrote a poem for my father, who has only ever read stilted and broken birthday cards from me, some years reading 셍일 and 사랑해, others reading 생일 and 사랑헤:

sad man,

I found while spring cleaning, a picture

I took of a banana you wrote

on, ballpoint

pen on peel, “only

banana” and I remember thinking

I don’t know what this means, but

this is how I want to remember you

thank you, sad man, for all the sandwiches

you’ve ever made me, no one else

will place so many things between

bread for my sake

and I want to tell my father, I wrote this for you when I was eighteen? Nineteen? In the years before that, too young as you well know, I was always writing for you and mother as if I were preparing for death (yours, hers, or mine). Please know I am so proud of you. Please know I love you so much.

I am waiting for the name built into the ground by the writers who came before me and twice-blessed by the writers who will come some unknowable time after I am dead.

These days, my mother sometimes asks me if there’s anything going on I’m not telling her. Specifically, she asks if I feel I can’t tell her things because she’s always coming to me with her difficulties. In these moments, my initial response is anger, that bitter sour tart spark when I want to spit at my mother, Why didn’t you ask me when I was younger? Why didn’t you consider making this space for me when I was a child? I long and I long, still, to tattle to my mother what’s been done to me.

These days, when the fear that my parents will die before I see them again is too great, I reread the letter my father wrote me, once, and tell myself that not everything has to be said. Not everything has to be written or spoken. It is possible and it is OK for things to be unsaid. But I also think about how it took a man’s writing, a man’s direction, the vision of men to move my father to open up to me, and it again takes me back to unknowable fruit, and I am unspeakably, heartbrokenly jealous at the thought that nothing I write may ever move my father in this way, that he has felt what he felt and opened as he did, then, and now that moment already exists, it already is.

Each impossible day, I am waiting for the name built into the ground by the writers who came before me and twice-blessed by the writers who will come some unknowable time after I am dead. The writers after that will come into that place knowing it is ours. The writers after that will unbind the ropes and let down the bells that mark the furthermost boundaries. I hold hope I might live to read some of these words to come.

This hope is why and how I really fucking love my job, my relentless job. I read and I read, even when I can’t write I have to keep reading, but sometimes I read a daughter’s story about a mother who is becoming a shadow and think, How is it that you are my student? My student’s story is slow green and fresh dying. I think about how my student will write five, ten years from now, and I hear the promise, I hear the unbound bells laid to rest upon the dark earth.

Theresa 학경 Cha writes, “Earth is dark. Darker.”

Theresa 학경 Cha writes:

Lift me up mom to the window the child looking above too high above her view the glass between some image a blur now darks and greys mere shadows lingering above her vision her head tilted back as far as it can go.

Theresa 학경 Cha writes:

Lift me to the window to the picture image unleash the ropes tied to weights of stones first the ropes then its scraping on wood to break stillness as the bells fall peal follow the sound of ropes holding weight scraping on wood to break stillness bells fall a peal to the sky.

I teach my students not to do this, a quote after a quote after a quote. Where is the analysis, I task them. Where are you in relation to the text?

Theresa 학경 Cha writes and she writes. She shows us how language can protect by keeping out as much as letting in. Her protection is invitation. Her invitation is protection. There she is in all the red above and all the blue below, which is and is not the home I am missing in a killing way, in a dying way. I have always been reading my way home.

This morning, I passed my probation. I thought of you when I received an official letter, jumbling my Korean name, notifying me that I am now fully confirmed in post, a full-time lecturer on a permanent contract, difficult to fire. I thought of my audacity to write to you, that first time, as if I am a participant in change for the better.

I asked for a revised copy, and now the letter mostly uses my name correctly, but closes with:

The Panel wish to congratulate you on the basis of your contributions to the Department of XXX.

I believe confirmation of post is something like tenure in America, but way worse. Not just because in America I could call myself professor. Still, it is a letter I would have liked to show my parents, but the misuse of our names is always stinging and it will be my father who will ask me:

XXX 는 무슨뜻?

But it will be my mother who is more loudly hurt by the thought that anyone could be so careless with something so important to me, to us.

Our first year or so in America, we lived in an apartment complex popular with immigrant families. The one next door to us had just moved from Germany, months after us. The parents spoke a little English, but their son, Amos, spoke none. Not even the word “apple,” which I had known how to say and spell when I arrived. Amos hardly spoke, period, I only ever heard him whisper in German to his parents, but we were both seven or eight years old and our parents wanted us to be friends.

One day, somehow, my dad became convinced that Amos’s father had been trying to tell him about a waterfall in South Carolina. We can fish there, my father said. And we can play in the water, like we used to. My dad was so excited in his gentle way. I hadn’t seen my dad so excited in America before. I could remember much better then, I hope, swimming after him in rivers and lakes, surrounded by family and friends who looked like us and talked like us. I remember dozing against my father’s back as he carried me across a favorite fishing spot, heading back to our campsite for the night. I don’t think it occurred to either of us to be afraid of the deep and quiet dark. We were together, marveling at the infinite stars above us.

Throughout the week, my dad stayed up late studying a road map of South Carolina. My mother chose the morning we set out early, and although she wasn’t sure about dad’s plan, she’d spent the whole day before preparing a picnic for us to take.

This was before I learned to be nervous about my mother’s cooking, before I told her I didn’t want her to pack me any Korean food for school lunches, before an elementary school teacher came to stand by my seat in the cafeteria, sniffing the air around me as she asked, “Why do you smell so sour?”

We drove and we drove. We drove until we grew too tired of empty fields and stopped at an ancient-looking gas station, most of its small glass front covered with flag paraphernalia.

Go inside and ask for directions, my mom said, and paused before handing me a five-dollar bill. And buy something if you need to use the bathroom.

Where you from? The man behind the counter spoke slowly and had a soft, warm voice.

Korea, I knew to say. South.

An young hah say yo! he said.

Were you in the war? I knew to ask. And the man behind the counter was real pleased and talked for a long time.

Do you know where the waterfall is? I asked.

What waterfall?

Then the man turned to the window and pointed out to the empty field across the way. I noticed a tree at the center, tall but not too tall, with a thick trunk and sturdy-looking limbs, but without any leaves in this sunlit season. Good for climbing, I remember thinking.

“That there is a hanging tree. Where we used to hang—”

What did he say? my mother asked.

He asked me where I came from, I said.

Where’s the change?

I spent it all, I said.

Why did you buy so much? You know we brought food from home. I was cooking all day yesterday. Do you want it to go to waste?

We never found a waterfall. The closest thing we found was a dam by some kind of factory or plant and we ate my mom’s picnic there, in the car. The drive home was miserable, my mother nagging my father for this senseless trip and everything else, me eating too many snacks, all the snacks, and feeling something soupy curdling in my stomach.

The story doesn’t end here.

That fall, Amos and I went trick-or-treating together, a first for us both. I was a witch and he was a scarecrow. Amos’s hair was the exact color of the straw his mother had glued around his sleeves, his eyes as baby blue as the checks of his flannel shirt. Amos still didn’t speak any English, at least not to me or to anyone I’d ever seen, but I remember thinking: He’ll be just fine with his hair and his eyes, he’ll be OK here.

At every door, I was the one to shout, Trick-or-treat, while Amos remained a step behind me, silent. But it was his costume the grown-ups cooed over; it was his hair the adults doling out the candy reached out to stroke. When our plastic pumpkins grew heavy, we trudged back home in silence. Amos’s dad was waiting for us on the shared lawn and invited me in. We sat around their kitchen table and Amos’s mom brought us juice. She asked me about school and how I liked being in America.

I miss my Korean friends, I said, looking at silent Amos.

Amos’s father went to the kitchen and returned with the largest bag of pretzels I had ever seen in my young life. He tore into the bag and began to scoop handfuls of pretzels into my pumpkin.

Amos is so shy, his mother said. Like his father.

When I got home, I showed my mom my haul. What is that? she said. Why are there loose pretzels in your pumpkin? Who put them there? Why would someone do that? She kept asking why, growing more upset, picking out the pretzels as quickly as she could and gathering them into a dish.

Maybe it’s normal in Germany, I said.

This is America, my mother said, pouring the pretzels into the trash. It was the first time in my life I had ever seen my mother throw unspoiled food away, my mother who ingrained in me so deep that rice is grown through blood, sweat, and tears of hard labor that to this day, eating the last bit of white, white rice from the belly of a porcelain bowl, I think I taste traces of minerals and feel a quiet stirring of awe and gratitude. This is where the story ends, in that small space that remains vivid still, in which I was stunned, momentarily, by my mother’s Americanness, so decided in doing something I thought I would never, ever see her do, and, in turn, my own Koreanness, held dearer to me.

I keep wanting to trace how I came to be here, one day, feeling so far away, in a position of power I could hold more firmly than hope. One day, I may move on from this tracing and find firmer footing in the love and joy of such an ugly exquisite sculpture made from desiccated squid. Desiccated squid hands, desiccated squid breasts, a skirt that is all desiccated legs, desiccated tentacles, one large painted eye, one red silk braid. Fi Jae Lee calls this piece Everything that Ascends to Heaven Smells Rotten, and it is the cover art for her mother’s book.

My first year on the job, in an outpouring to a colleague I trust about the fear of getting fired during probation, the kind and gentle colleague said, Well, just try not to kill anyone. I found this very reassuring. I thought, Yes, I can do that.

*

As I prepare to enter the fourth year of my first permanent lectureship, theoretically as secure as I can be in my post, I feel just as unsettled as I ever was, albeit in unimaginably different ways. I don’t know what to say to students who ask me how to write in these times, but this is what worked for me: Accept that you are second-rate. Be soup? Be sick? Be sick a lot. Cry all the time. But, also, be furious. Hold your fury close. Forgive nothing. Maybe some things. Stay bitter, though. And be sure to stay other words, too. You are sour. You are tart. Be delicious without shame. Toni Morrison said of those who would follow in the work of Black women writers, “They will write infinitely better than I do. They will write all sorts of things that no one writer can ever touch. They will be stronger, and they will be delicious to read.” You are a reader. You are a writer. No one can grant or deny you stars. The real stars are in the sky all around you at all times, at all times dead and dying. Know these things well but also not really believe the words. Write until you find something that can only be surmised as balance while knowing that this is not the right word. Write new words if you need to and stare down anyone who tries to tell you to put them in italics or include a glossary because this is how things are done. Ask why. Ask why without a question mark at the end. Say all the silent parts out loud. Thrive in discomfort.

I can see myself continuing to ease into a life where I have maybe too much room to feel small deaths, too much room to make them poignant for myself.

But, also: Ask for help. Trust deeply in the kindness of writers and readers who help you.

But, also: Keep questioning how much of the work we do relies on what we name to be trust. Recognize there are many animal-things we so name. Delicious things. Gently-gently. Lovingly. What kills.

Survive. Cope. Get through. Think about getting out. Stay in that space of possibility. Get out if you really need to. Leave as safely and as strongly as possible.

I know even less what to say to students who are being evicted from their homes, losing jobs, losing disability support, losing mental health support, losing family, losing loved ones. So many of my students have never been able to afford living in London in the first place, and now I can only imagine how the days may feel like a recurring nightmare. I am sorry. I will keep trying to imagine, as do the writers whose books I hold close and stack together and hold close and stack together until I am not my job. 언니라고 불러도 될까요? 잘 부탁드립니다.

I will keep trying to stay healthy and happy enough to keep trying.

I have daydreams of being able to fund a scholarship for first-generation immigrants to pursue higher education, abroad should they wish, as I did. I have daydreams that some will choose to go home. I have daydreams of naming such a scholarship after my mother, after my father. My mother first, so that I can take her by the hand and say, Look, what you did for me, what you did for your sisters, I will do for others. I will do so without grinding down my bones as hard as yours. I will do so comfortably. I realize I am already settling into a life of such comfort to dream in this way.

If my book does well, I could negotiate with that power. I could teach less. I could write more. And now I have, not one, but two dream agents: an agent in London, an agent in New York. They are agents I would not have had access to without my job. In our first conversation, my London agent said, so surely, “I mean, you know when something is finished.” And I found that I could really hear her. I found that I did know, or, at least, I could see how I might get there. And I found this startling.

I should confess that I did not pick the lavender myself. It was picked for me, and I, in turn, picked up the bundle at a drive- through, socially-distanced farm shop where the purveyors had rubber-banded a card-reader to the end of a fence post that they held out to the driver’s-side window.

I paid London prices for fresh lavender. I held the lavender with both hands and it felt so luxurious. Just as I was about to dip my head into the bouquet, I noticed some kind of large insect attached to one of the flowers. I shrank away and closed my eyes and asked my partner to pick it off gently-gently.

When my partner passed the lavender back to me, I saw half of the insect still attached, filaments of something silken and fibrous furling out of the broken shell, some cocoon or chrysalis or whatever that stage is, before, before.

“You killed it,” I said, too sad for such a small death.

“Circle of life and all that,” my partner said, too easily. It made us laugh, the absurdity of what he said, how he said it, as if any of this, all of this all around us, our gesturing wildly with both hands all around us, is easy. We talked about The Lion King and I even sang some of the song and we laughed most of the way home because my partner didn’t mean what he said. This small death pained him just as much as me, possibly more, as he was directly responsible.

I can see myself continuing to ease into a life where I have maybe too much room to feel small deaths, too much room to make them poignant for myself, too much room where I risk losing sight of the immediacy and urgency of harder, harsher truths. I worry about growing soft and sheltered, which I know, or I used to know, better the further back I reach, I know this kind of safety lends itself so easily to cruelty. Going forward, I can see how easy it would be to tell myself that it won’t happen to me.

I won’t stop worrying that my writing will grow confident in a way that is careless and I won’t stop worrying that one day no one will be around to edit me because I will stop listening.

There will never come a day when I look back on the words I wrote here, for this other book that is not a novel, while trying to survive a new job and an unprecedented global pandemic—and feel shame for so exposing my own desperation.

I will open this other book with the only Korean poem I have ever written. The Korean used is likely broken and outdated—but it is my own. The poem came to me as fully formed as it could be (considering my mutated Korean), in the span of time it took for me to walk from my childhood bedroom to the kitchen of my family home. In the poem, I am home alone with my father, observing him doing dishes at the sink, while my mother is away in Korea visiting her dying sister. The poem makes no direct mention of my mother coping with her sister dying, noting only my mother’s absence. There is some sense that my mother might be dead. My mother and her sister were the closest in age of their siblings, and my mother tells me they looked very much alike in their youth with their snow-white, full-moon faces. They are present, my mother and her sister (my aunt I hardly remember as she is dying), in the poem’s closing focus on a rice bowl my father holds, gleaming like a pearl.

I translated the poem into a monologue from my grieving mother. When I asked my partner to read it over, he made that oof sound he makes when he reads my work before very sweetly expressing his concern for my mother. Would she be upset by this airing of our dirty laundry? I got what I’ve been told is prickly and I told him, This isn’t my actual mother actually speaking, my mother doesn’t speak like this, my mother doesn’t speak English. I got what I’ve been told is sharp, but I know you know that the voice I am writing is not my mother’s. Through this imagined, other voice of my mother, I found room to speak to things unsaid between me, my mother, and my father. I know you know that when I say “unsaid,” I mean the saying and the not and the taking back, too. In the monologue, instead of speaking directly of her sister’s death, the character of my mother poses questions around both the possibility and certainty of her own death and how my father and I would survive. The poem and the monologue are extensions of one another, sisters in shared in-between spaces. I know you know that if you have only ever lived with one country to call home, I can’t explain that kind of dark to you, out where nothing lasts, not even God’s house.

In the months after my confirmation of post, my department will add a new section to the form we are tasked to fill out in advance of research productivity meetings. It doesn’t happen yet, not in the space of time in which this letter to you opens, the space in which I am writing to you on the bright morning of my confirmation with birdsong at my window, the confirmation I worked so hard for that it becomes easy to think words are more reassuring than they are not. But this is what writing can do. Writing can reassure and writing can upset, writing can disrupt. Writing can control time at will and I can evoke the aftermath of a book before the book is finished.

__________________________________

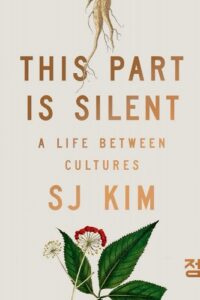

From This Part Is Silent: A Life Between Cultures by SJ Kim. Copyright © 2024. Available from W.W. Norton & Company.

SJ Kim

SJ Kim was born in Korea and raised in the American South. She resides in the UK and teaches creative writing at the University of Warwick.