The passport could not be procured. The women would not be seen by the administrator, or by his supervisor, they would not. When they asked for someone of authority they were ignored. They had filled out the application form, provided payment, submitted the accompanying documents: the birth certificates, the naturalization certificates and/or the proof of birth abroad, the state-issued identifications, the baby pictures, and the baby hairs. But they would not be seen, not now. They sat, waiting. The chairs were not comfortable, intentionally so, but they tried to get comfortable. The others walked up quickly, received a stamp, left with the burgundy passports in their pockets, well on their way to lands and/or seas. The women crossed their arms against their bosoms, their legs bent and crossed one over the other. The women watched these others come and go. The woman sitting near the wall sat low, with her neck on the back of the chair, looking at the ceiling and at the one window. The government building was in ruin. The paint was chipping, yellow paint with green undertones. A ringing phone went unanswered. The air was cold. There was the one window and its glass that showed blue, a cloud. The pair did not know how long this would take, they had brought snacks: rosemary crackers, yogurt, tangerines, string cheese, blackberries, seared scallops. Also sanitary napkins, floss. This was bureaucracy in action. It was plain. While they waited they were allowed the use of the restroom. They took turns. When they were emptied and still, they spoke:

See, Yvette?

What?

See? There.

What?

The glass, that part of the glass in the window, see how chipped it is?

Yes, I think I see—

Well, that’s a shame.

This is all a shame.

Yes. (pause)

And I can feel this damned wind coming in, from the crack, can you feel it? (pause) You don’t feel it? I feel it right on my forehead. The air is coming in from the crack, right there, see, that hole right there? It’s so damn windy in here, and there’s only one window, and the only window in the place is broken, how about that, and why not open it up and let everything in?

Should we open it?

No. No, but someone should, someone might as well open it. It’s really something, this place, and this damned window, it’s practically wide open.

Yes.

Wide open, it is. (pause) Wide like Betty’s mouth (laugh), remember Betty Davis? Betty? Betty Davis with her mouth ajar, or Mabry, Betty Mabry with her mouth ajar, Mabry, no, it’s Davis, I should call her Davis, Miles didn’t treat her well, he didn’t treat women well, did you know, for a year he treated her badly, and twenty years her senior, the name Davis belongs to her, I’ll call her Davis, but do you remember that photo of her with her bottom teeth showing, her right breast leaning into the center, remember? In Vibe Magazine with her legs apart? How could you not? It was in Vibe or Ebony or something, you don’t remember her straddling the motorcycle in the (sucks teeth), the zebra print leotard and those sheer stockings, the fingers all painted red, a dark red, not a light red, a dark red, and her hair reaching up high, with all that metallic eye shadow and the opened nostrils, her shoulders covered with feathers?

Um, I don’t think I remember that—

Well, that’s what I wished to look like, like Betty Davis with black feathers on my shoulder blades and white-and-black leather boots (laugh), and when she whines, ooh, when she whines from the gut and she yells about fucking, oh alright, excuse me (laugh), sorry, sorry, boning, getting busy, you know, knocking boots or whatever, using her throat, using men, using men, or even being the mistress, being their flower, a flower, she’s not being submissive, uh uh, no sir, she owns them, she owns them, they beg for her and that’s who I most wanted to be like. And I’ve tried before to be like her, even though hers was a performance. (pause) You know I met that man in the street. (pause) Remember him? The man with the suit? He wore a hat and a suit, a really fine suit, he always seemed to be in some sort of a rush, his pace was quick (laugh), his suit moved around his body as he moved, he moved quick, quick, the material was expensive. (pause) I could tell by how the material moved around his joints, how it moved around his elbows and his knees. While he moved quick the material moved slow, and he moved between people real agile like while he carried a single banana in his left hand, gripping the single banana, and it left an impression on me, you know? What a thoughtful thing, I thought, him bringing sustenance to wherever he might be going next, a job interview I thought, but he held no leather briefcase, no résumé, only the yellow banana, a fruit I never liked, too soft, too sweet, so then I thought he might be rushing to a person, a woman, or even a child, and later I thought maybe he just liked walking quick like that, sometimes too quickly, but I was hot on his heels. The skin on his heel was dry, it scratched my legs as he climbed over me—

I remember him now, I remember—

And for months we saw each other, months, weeks, in secret you know, and it was thrilling. (laugh) Always the smell of cut grass in the background. We wouldn’t talk much, we didn’t have time, but we had rhythm. Rhythm, we did. (pause) Like Ali when he rode the horse outside the Apollo with the black cowboys, remember, with the red-and-white checkered tie, and how the horse looked so small under Ali, and I looked small under the man with the banana, his shoulder with the stitches still healing, his stomach protruding like a soon-to-be mother, with his navel protruding, an outie, and two bags sitting under the closed eyelids, and when I rode him I touched the belly button and his top teeth would bite down on the bottom lip, the golden teeth and the wide bottom lip, wide, glossy with spit, nose flared, and the yellow always set against the purple of his left hand. He held the banana as we moved, and I didn’t understand. I asked him, why? Why don’t you let it go—

That’s strange, it’s a very peculiar thing—

Let go? He said it as if considering, but he wouldn’t. He wouldn’t. I didn’t ask again. (pause) He ate popsicles whole. Someone was constantly cutting the grass outside the window, a window like this small one here. Once while he slept I tried to pry it from his hand, but, no, he wouldn’t and I couldn’t. I think he did release it when I wasn’t in his company, though, because sometimes the banana was cold to the touch, cold as if it had been refrigerated. By the third month the fruit was too ripe, brown, black, inedible, cold and too soft.

__________________________________

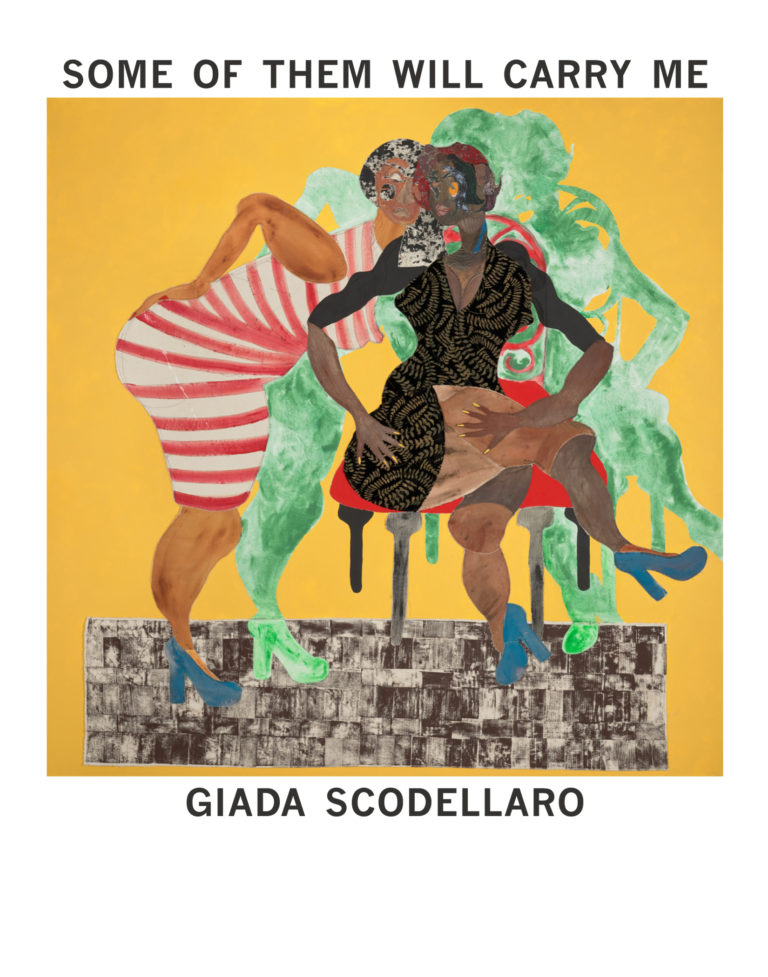

From Some of Them Will Carry Me, Scodellaro’s debut collection, out now from Dorothy, a publishing project © 2022 by Giada Scodellaro.