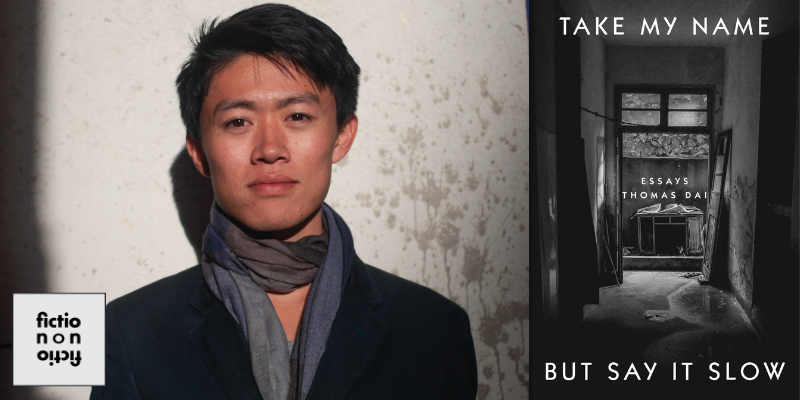

Thomas Dai on Mapping, Naming, Borders, and Immigration

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Essayist Thomas Dai joins co-hosts V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell to discuss his new collection, Take My Name But Say It Slow, in which he writes about place and identity. Dai talks about the imperialist impulse behind Trump’s attempt to turn the Gulf of Mexico into the “Gulf of America,” the power of naming, and the appeal and uncertainty of mapping. He also reflects on the surprising history of border policing, queer cartographies, and the sometimes paradoxical relationship between inner self and physical space. Dai reads from Take My Name But Say It Slow.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: That makes me think of the essay “Borderlands Transect,” where you’re talking about living in Tucson, which you’re not from. You were there for an MFA program. You were new there. You were trying to figure out what it meant to live close to the border, as you were then. Could you talk a little bit about what a transect is and how that essay developed?

Thomas Dai: Yeah, of course! So I guess the minor backstory to this is before I did an English or MFA program, I had not been an English major in college; I had been a biology major. Both my parents are scientists, and just in a sort of classic, maybe second-gen Asian-American way, I was just following in their footsteps as much as I could. But one thing that I learned in one of my classes as a biology student was about this very simple idea of running a transect, which is basically a field survey technique, where a biologist, or anyone who’s doing land-based research will basically just chart a line of a certain length, a straight line, over a particular landscape.

In this essay, I’m thinking about the American Southwest, the Sonoran Desert. And you just walk kind of methodically along the line and every five feet, or whatever kind of increment you choose, you stop and you take counts of things and take stock of what you’re looking for. And it’s a way of just quantifying something that’s very difficult to quantify: landscape. And so that essay really developed for me because when I was living in Tucson, it was like this terra incognita to me, and so I leaned on the techniques I learned as a student to try to figure it out.

I wasn’t actually running a transect, but in a metaphorical way, I felt like my daily life was just kind of walking around, going to class, exploring this sort of Western landscape that I never really been exposed to. It did feel like I was running a transect, but I wasn’t really sure what kind of question I was orienting this transect around. And I think what unlocked that essay for me eventually is obviously being in the southwest and reading the news; I was thinking about the border, and I was thinking about border politics, and this made me dig a little bit into the history of the border, and I just realized that how that border came to be was in a sort of similar process.

After the Mexican-American War, when we were ceded this territory that had previously been Mexico, a border had to be assigned, and people did that by walking what amounted to a transect. There wasn’t a line already there. They agreed on one, and then they had to survey it and draw up maps. Just like I reflect over and over again, that’s a subjective process. It wasn’t like an ordained process; a Mexican committee of surveyors and an American Committee of surveys had to keep on checking each other’s work and deciding was the line actually supposed to be here or there.

So I think in digging into that history, I saw this kind of curious parallel, and it helped me form the essay where that transect was formed, as in the literal border transect, formed the basis for a lot of this political strife that I was thinking about, that just immersed my daily life as a resident of Arizona, but then I was also trying to write my own transect through that to figure out how I could position myself in relation to those things that were going on.

WT: Since we’re a literary and political podcast, I have to bring up here the novel Mason & Dixon by Thomas Pynchon. I don’t know if you guys are familiar with that, but it’s another book, a really good book, about surveying and the political meaning of surveying, and how the Mason-Dixon Line was actually drawn, and what it meant. And there’s a similar process going on there. So anyway, I thought about that while I was reading your essay. And I think that that idea of the physical process of drawing borders, but what that means metaphorically becomes very complicated.

TD: Yeah, I think it is very complicated. And ultimately, I think I say something very simple, but that took me a long time to figure out in that essay. Just as I don’t trust my transect, as I don’t think it’s actually answering anything about my identity or my place in Arizona, that level of mistrust should also be applicable to the transect that those surveyors ran, and that they were themselves also constantly questioning, this gigantic trek that they took from the Gulf of Mexico toward the Pacific.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: So as I was reading this essay, I was thinking about my friend Peter Ho Davies, who wrote a book called The Fortunes. It’s four different connected novellas, which are in part about different time periods in Chinese-American life. You also write about Chinese immigrants being taught by a specific person to pass themselves off as Mexican. I had learned about this a few years ago from a friend of mine, who’s an immigration historian, but a thing that I didn’t realize, which is so fascinating, and pretty horrifying, is the connection between the Chinese Exclusion Act and the present day Border Patrol. Of course, we’re currently seeing communities all over the country just in fear of ICE raids. At some universities, you’re getting instruction on what to do if ICE shows up to your classroom. Workers in California are not showing up for work. In Chicago, Tom Homan is mad that people know too much about their rights. Can you talk a little bit about how the Chinese Exclusion Act led to the concept of so-called illegal immigration?

TD: Yeah, of course. And this is something that I was also super naive about until I started reading into the history of the border and the immediate tie-in was learning—and I think this is on the border patrol’s own website—that early on, before it was constituted as an official agency, they referred to it as the Chinese division. And it was more localized, but it was specifically there to stop the border crossers that mattered, at least in public consciousness at that moment in time, which were migrants from China that, because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, were different from prior and also contemporary migrants of that time. They were suddenly by law not supposed to be there.

And this is very complicated, because at the time, and prior to the Exclusion Act, migration had been happening,and it had been connected to moralizing and discrimination. So one thing I want to be clear about is that I’m not saying, “Oh, the Chinese were the first to carry all the negative connotations of being an illegal immigrant.” I think what history reveals is something more legalistic than that. It wasn’t that the Chinese were welcomed before the Chinese Exclusion Act, and it wasn’t that Mexicans migrating across the border weren’t under duress as well. It was quite simply, that there wasn’t anything in the books that was saying this class of immigrant from this nation of origin is not allowed in this country, and therefore for them to cross the border is breaking the law of the land. And you know, this just brings into stark parallel just how contingent these terms are to the time.

I think about this in my conversations with Asian Americans in my own community. Whether they’re political or not, I think a lot of them have this imagination that they’ve always been the good immigrants, or if they weren’t the good immigrants, it was all the fault of the US government. And for some reason, they draw a tight distinction between their immigration history in this country and the current immigration crisis going on and all the political rhetoric around it. And so for me, both for my own personal edification and just so that I could talk with some evidence to people in my life who think like this, that really succinctly tied it together for me. For long periods of Chinese migration to this country,we were illegal immigrants and were laden with all the baggage and xenophobia that comes along with that.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Keillan Doyle. Photograph of Thomas Dai by Liam Davidson.

*

Others

National Archives, The Chinese Exclusion Act • “Queering the Map” • Mason & Dixon by Thomas Pynchon • The Fortunes by Peter Ho Davies • “Think There’s Nothing You Can Do to Stop ICE? Think Again.” | The Nation

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.