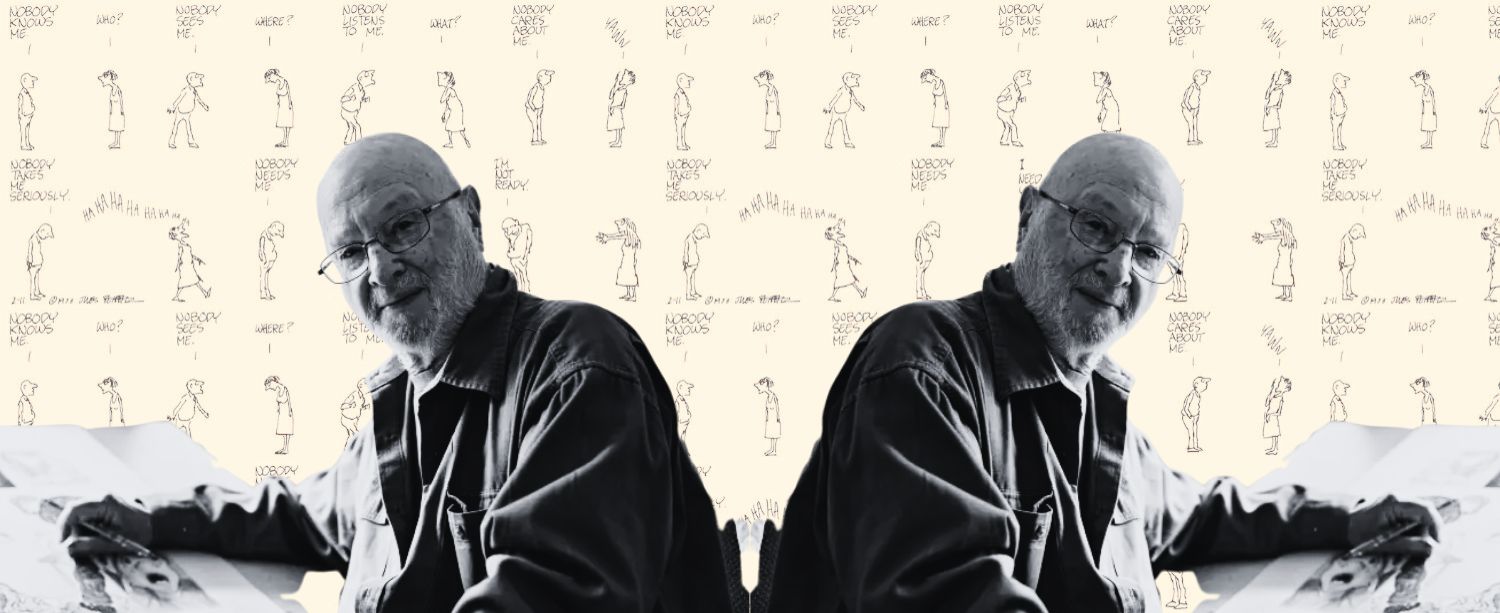

“This Will Be Fun.” On the Life and Times of a Comics Master, Jules Feiffer

Paul Morton Considers the Artist Who Took “Aim at the Radical Middle”

In the summer of 1946, Jules Feiffer, then 17, determined to make a career in comics, entered the studio of his hero Will Eisner. At 29, Eisner was an eminence in an industry that had just moved on from its Wild West era. His most famous character, a Sam Spade-esque ghost detective named the Spirit, was a superhero for sophisticates.

Feiffer had been studying Eisner’s work for years, having first encountered The Spirit as a seven-page Sunday insert in the Parkchester Review, a weekly published in what to him was a fancy neighborhood, two subway stops uptown from his home in the Bronx. The Spirit had an existential streak, and unlike Superman, he was often unsure of his victories. Feiffer admired Eisner’s noir stylizations, smart dialogue, as well as his Welles-ian compositions, at once grand, elegant, and brutal. “When one Eisner character slugged another, a real fist hit real flesh,” he later wrote. “Violence was no externalized plot exercise, it was the gut of his style. Massive and indigestible, it curdled, lava-like, from the page.”

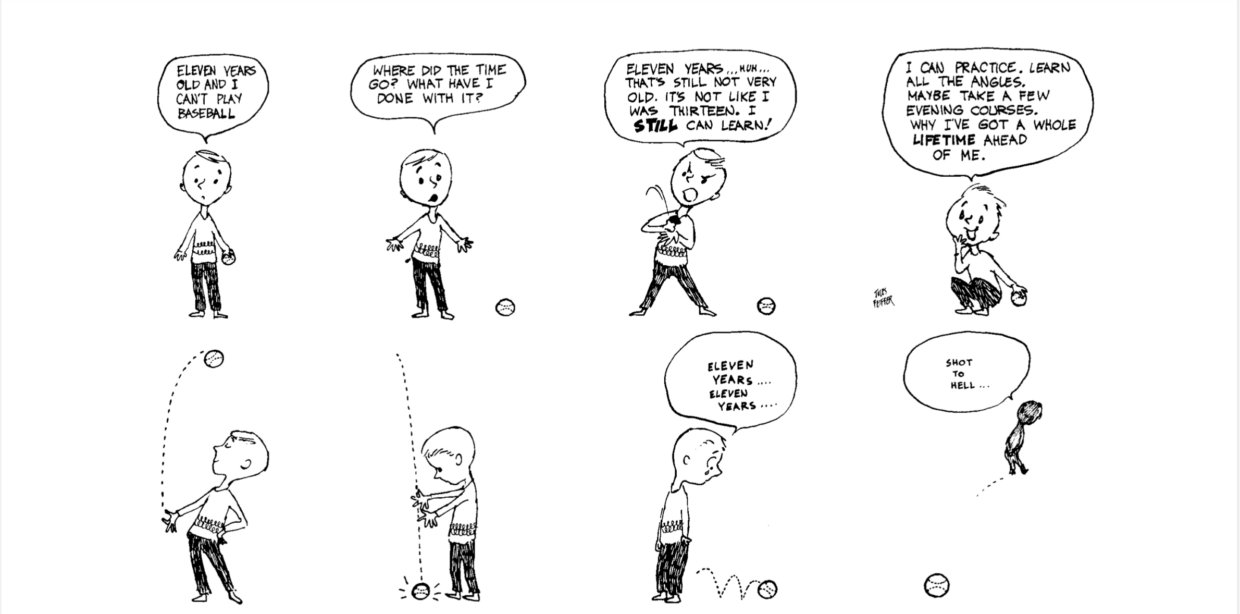

From Feiffer, 1956. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

From Feiffer, 1956. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

Eisner gave Feiffer a drawing test, which he failed. What he needed was “a brush line which used thick and thin with great facility,” he told me, decades later. “I couldn’t do that then and I can’t do that now. I was in love with a skill that it turned out I had no vocation for.”

Feiffer saved himself by immediately revealing an encyclopedic knowledge of Eisner’s career, and a graduate-level talent for critical analysis. He was not so much a fanboy geek as a proto-pop intellectual. It was all very flattering for Eisner, who had years before predicted that comics would one day enjoy the status of high art.

Eisner offered Feiffer a ten-dollar-a-week job as an assistant, and then the opportunity to provide, unpaid, a children’s strip to his comic. Three years later, when Feiffer was 20, he got to write his own Spirit story, “Ten Minutes,” a tragedy told in real-time about a boy who commits murder and then meets his end on the subway while on the run from police. It reveals Feiffer’s preternatural timing and his jazz musician’s ear for the Bronx vernacular. The children’s strip has merits, but “Ten Minutes” is a classic, and it marks the first great accomplishment of one of the longest literary careers in American history, a career that ended with Feiffer’s death on January 17, nine days short of what would have been his 96th birthday.

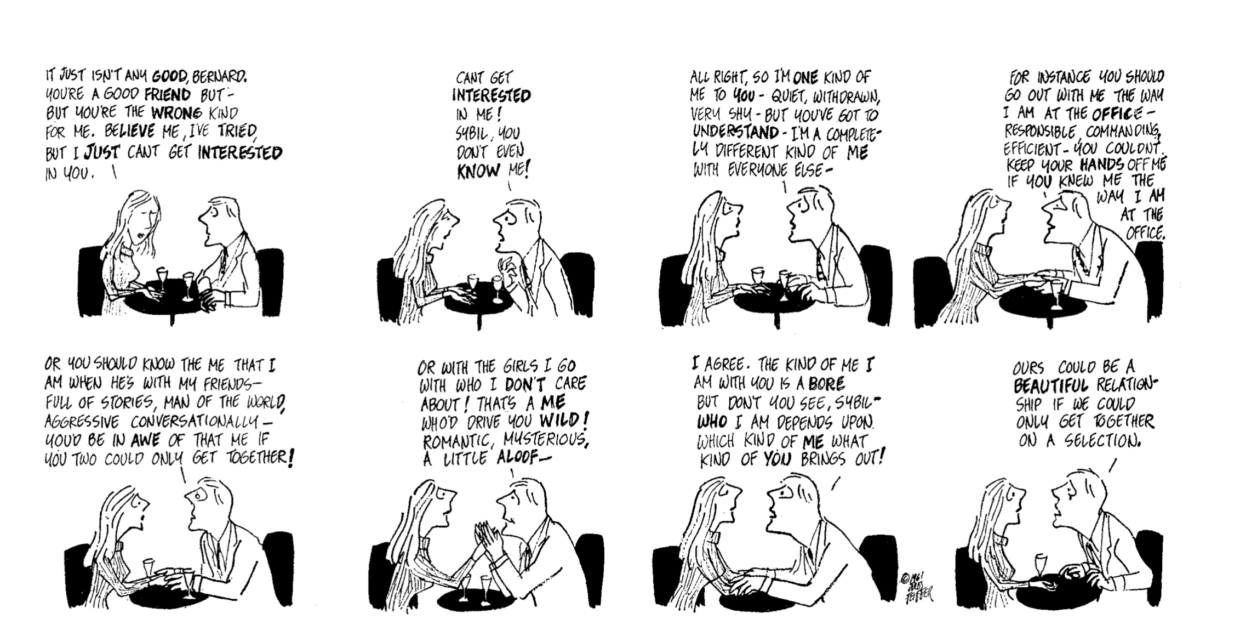

From Feiffer, 1961. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

From Feiffer, 1961. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

Feiffer was a chronicler of the American berserk. His fellow travelers included Mike Nichols, Stephen Sondheim, and Philip Roth, his admirers Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Gene Kelly, and Bayard Rustin. A generation of adult-wary teenagers adopted his first collection, Sick, Sick, Sick, as a talisman, and a slightly younger generation studied his illustrations for Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth. Feiffer wrote the screenplays for Nichols’s Bergman-esque masterpiece Carnal Knowledge and Robert Altman’s legendary disaster Popeye. Some of what you have just read made it into the obituaries. Unmentioned in them is damning evidence of our criminal willingness to discard our greatest cultural artifacts. Feiffer’s strips for The Village Voice and satires for Playboy—his most vital work—are out of print.

Feiffer ghostwrote the final years of The Spirit, but he didn’t draw his first substantial comic stories until he entered military service. A couple of years after he came home, he started shopping his strip to every magazine and newspaper in New York. The Voice, the intellectual organ of the still young Silent Generation, took him on under the condition they wouldn’t have to pay a dime.

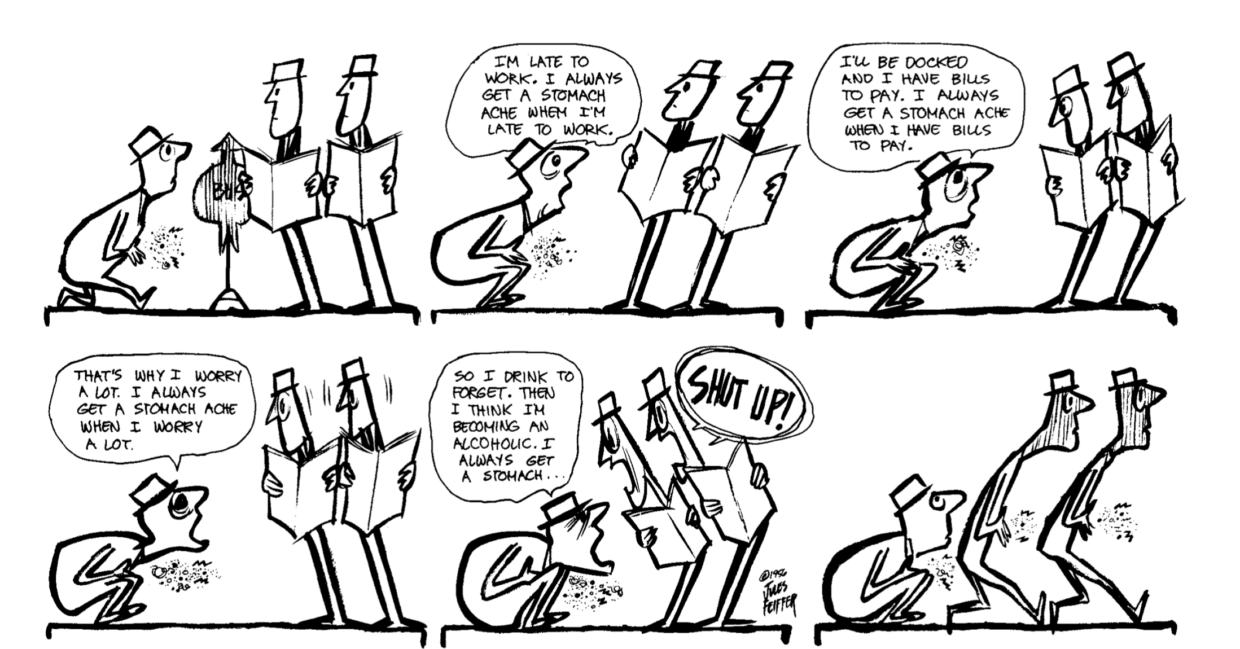

Feiffer’s strip, Sick, Sick, Sick, debuted on October 24, 1956. He had not yet developed the neurotic, character-driven style that would define his voice. The line is thick, heavy, and angular, a post-war, modernist aesthetic borrowed from UPA. The story, however, is more autobiographical than anyone, including its author, probably realized at the time. It features a man on his way to work, suffering from a stomachache due to anxiety. He’s caught in a vicious cycle. “So I drink to forget,” he says. “Then I think I’m becoming an alcoholic,” which leads of course to another stomachache. “Shut up!” shout the two men to whom he complains, before walking off with stomachaches of their own.

From Feiffer, 1956. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

From Feiffer, 1956. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

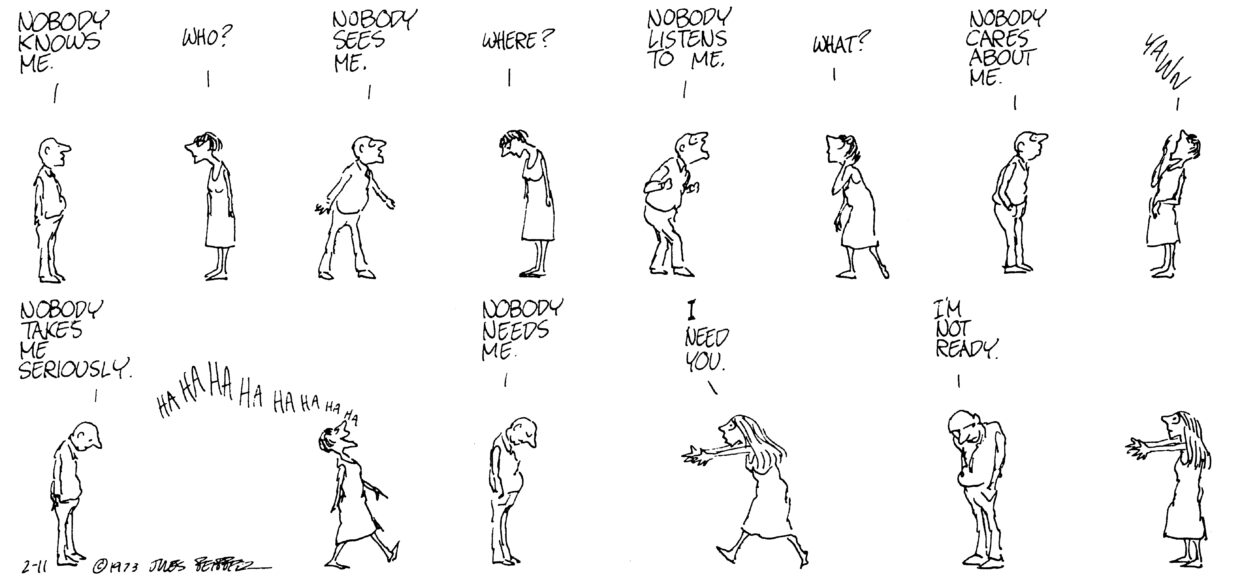

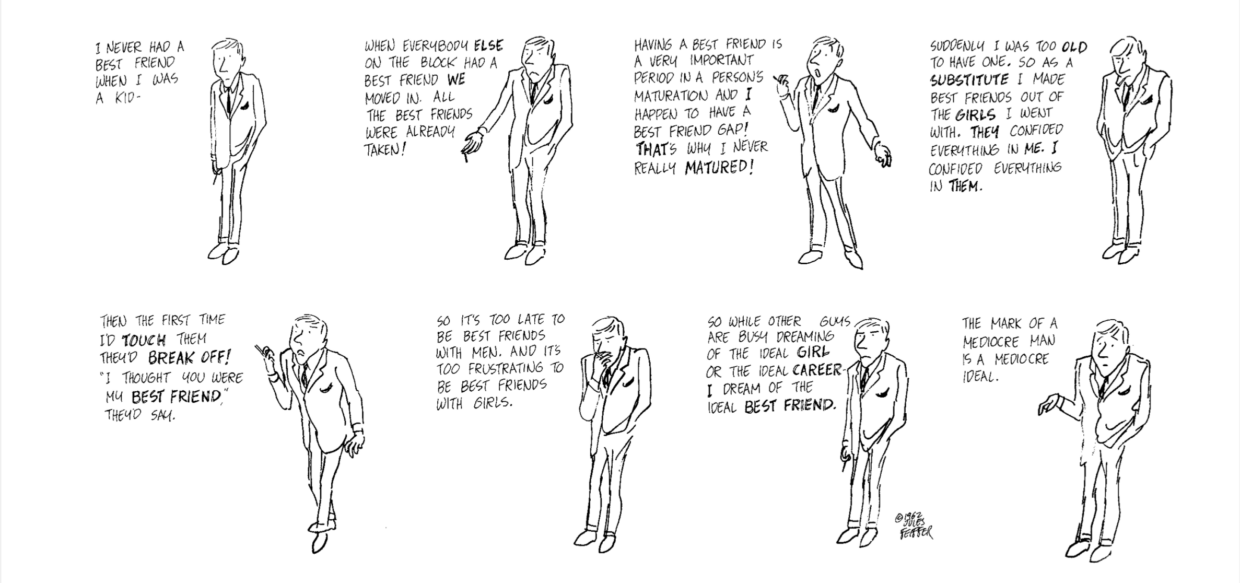

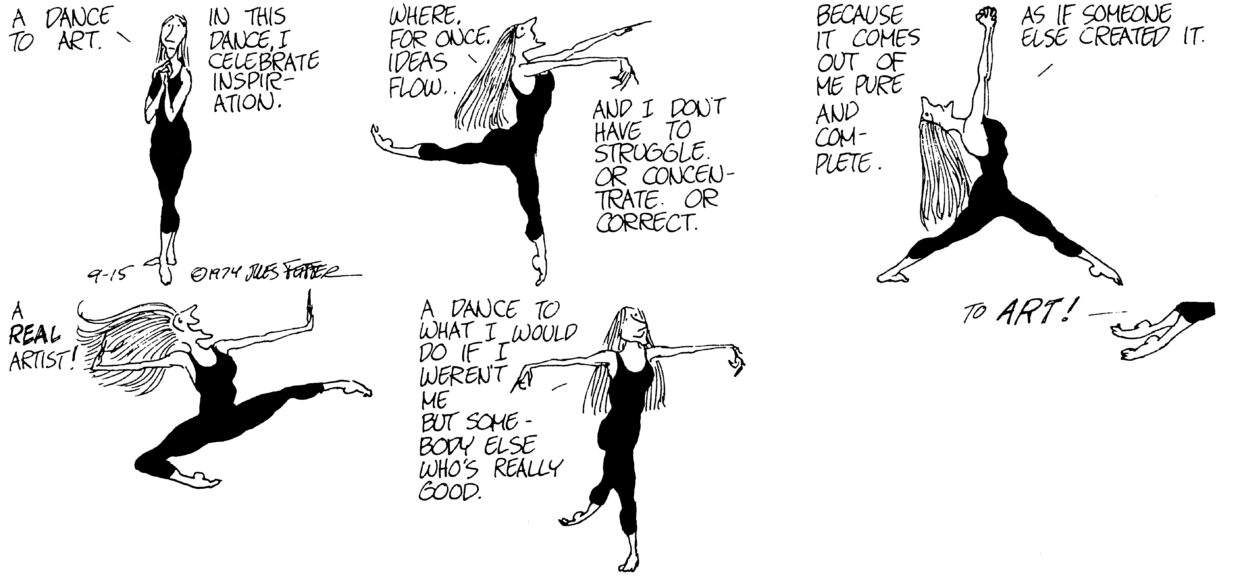

Sick, Sick, Sick was eventually renamed Feiffer, and its eponymous author would make several innovations over the first decade of its run. He removed spaces between panels, allowing images to flow into one another. He eliminated balloons and drew dialogue and characters in the same style; the approach created a unity of image and language and the illusion that the words emanated from somewhere deep within his characters’ bodies. The punchlines, if punchlines they were, often appeared on the second to last of his drawings. He was less caricaturist than portraitist. Every person he depicted had lived a full life before the strip began and would continue to do so long after it was over. Feiffer’s strips were modern short stories.

He changed his style after a few months, when, out of curiosity, he dipped a pair of wooden dowel sticks into ink just to see what would happen. The line became looser, more frenetic, more appropriate to describe the always on-edge inhabitants of Greenwich Village, living in the shadow of the bomb, awaiting the pill. A woman stood up on a blind date blames his terrible behavior on “compulsive social behaviors or erratic interpersonal adjustments,” before regressing into solace. “I hope he works it out soon. I’m tired of waiting.” Feiffer’s alter ego was Bernard Mergendeiler, a less likable version of the Woody Allen character. A dancer who Feiffer dated for a short period inspired his greatest creation.

From Feiffer, 1966. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

From Feiffer, 1966. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

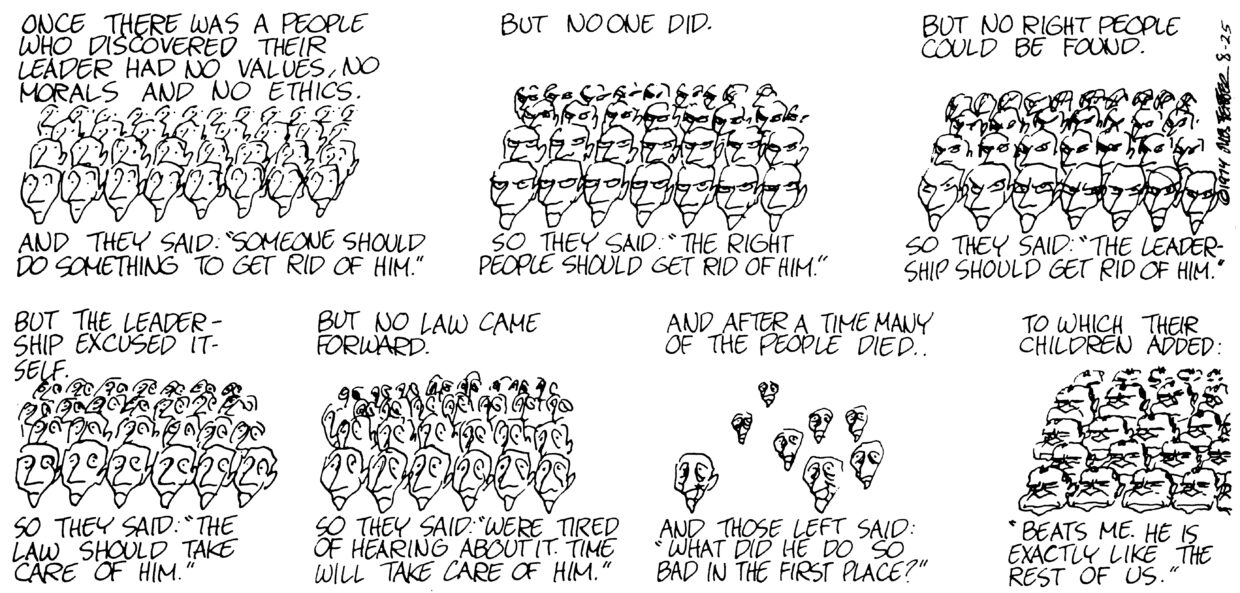

His political cartoons are bleak because they’re true. A politician declares the invention of a nuclear weapon so big it will blow up everything. As a result—good news!—it won’t cause any fallout. “It’s 100% clean.” His civil rights cartoons took aim at Northern white liberals. The most articulate indictments of both Cheneyism and Trumpism can be found in Feiffer’s Johnson and Nixon cartoons.

In the spring of 2009, Fantagraphics published a hardback collection of his first decade of strips, and I met him for the first time that March, at his apartment on the Upper West Side, to interview him for the now defunct website Bookslut. The transcript of our conversation was solid, but it didn’t capture his distant affect. He was nearing the end of his tumultuous second marriage, and I think he was still bitter over his break with the Voice in 1997. He stared ahead at his blank television for most of the interview, and he smiled once, when his cat jumped on my lap and started grooming my hand.

“I knew I needed an outlet for my political rage,” he told me. “It’s true of any time, but in this particular time of suppression, I had to be entertaining. I had to be funny. It couldn’t be a polemic.” He rejected what he saw as “confessional moralizing” in the alternative comics of the aughts.

Feiffer has been called a pioneer, having come of age at a time when humor in popular culture avoided politics. Maybe, but Feiffer’s work doesn’t have much in common with what followed. Unlike The Simpsons, his strips are hard to quote, for his language is elliptical, unsuited for one-liners. He avoids reference humor and respects his characters too much to sentimentalize them.

I was surprised when he said he liked The Daily Show, for Feiffer, unlike Jon Stewart, never sought clapter. His strips aim directly at the “radical middle,” the centrists who defend the military industrial complex and the Vietnam War, who want a slow-down of the civil rights movement. Stewart made a frenemy of Bill O’Reilly. The Feiffer of the 1960s would have considered him pathetic and dumb, too boring for satire.

From Feiffer. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

From Feiffer. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

He often talked about his fathers—Eisner, as well as E.C. Segar, the creator of Popeye, Milton Caniff, the creator of Terry and the Pirates, and the trio of New Yorker cartoonists, Saul Steinberg, André François, and William Steig. He was uninterested in brothers, with the exceptions of Shel Silverstein, who created the line that could dance, the caricaturist Ed Sorel, and his fellow playwright/cartoonist Herb Gardner. Mad magazine, he complained, never took a side on anything that mattered. He respected Charles Schulz, but he didn’t emulate him. He shared with Marvel the same audience of cool college kids, but he never bothered to open a Fantastic Four, and he never got Robert Crumb or the underground comix movement. But in the aughts, when he was in his seventies, he started reading graphic novels. Among his sons, he named Daniel Clowes, Craig Thompson, and David Small.

Five years later, he published a graphic novel of his own, Kill My Mother, a noir tale, which would be followed by two more to form a trilogy. His genius for language was fading, and he was never a natural for long-form narrative. And yet, a micron pen allowed him to realize the fluid, visceral action line that had eluded him since the 1940s. At 85, he had finally passed Eisner’s test.

*

In 2019, when I contacted Jules again, he was on his third marriage to the artist and writer Joan Holden, and living on Shelter Island, a short ferry ride away from Sag Harbor. I sent him an essay I had written about his relationship with Hugh Hefner, a one-time aspiring comics creator himself, who had helped Jules hone his craft. I told him I wanted to write a book about his oeuvre. “I better call my lawyer,” he said. Then he gave me the same directive he had given himself many times through the years: “This will be fun.”

I met him in September. We sat in a small, cramped living room taken up by a grand piano, the walls covered with Joan’s paintings and just one of his drawings. His desk was tiny, tucked into an awkward place just next to the front door.

From Feiffer. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

From Feiffer. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

He was at his desk every morning, there to attack his fourth graphic novel, which was published last fall. If he got up in the middle of the night he would sit down for a 15-minute session that would last two hours. He fought macular degeneration. His memory was fading and he had to relearn stretches of his narrative from one day to the next. It wasn’t a problem. This was simply how the work had “ordained itself,” he told me. At a certain age, you know that the “dead” in “deadline” is literal, and that it may be best to keep your projects short. I wondered if he believed in his mortality.

He missed his life as a Zelig. He had served as a key witness at one of Lenny Bruce’s trials, and campaigned for Eugene McCarthy in 1968, alongside Robert Lowell and Paul Newman. He had been a drinking buddy of James Baldwin, though he couldn’t remember a thing they talked about because he had been drunk. He had improvised comic routines with Philip Roth at Bob Brustein’s parties, though he couldn’t remember any joke they told because he had been drunk. He had stayed at the Playboy Mansion when he went to Chicago—to oversee his early theatre experiments at Second City, to write and illustrate a book about the Chicago Seven trial—though he didn’t have any stories about his nights with Hugh Hefner because he had been drunk. His memory came back when I showed him his work. He analyzed the faint move of a marker in his 1979 graphic novella Tantrum, the geometric relationship between words and bodies in Feiffer.

“I was a literary-bohemian drunk. Chardonnay, cabernet, martinis, scotch. For fifty years. Never missing a deadline.”

The Jules I met was not all that different from the one I would have known in the 1950s: an egomaniac who swung between self-aggrandizement and self-criticism. He could be warm one minute, preoccupied the next. Like many great writers, he was more judicious with his fictional characters than with the people in his life, each of whom was either the nicest person you ever met or an arrogant jerk.

His comics, and later on his plays and even his children’s books, helped him come to terms with his failings. He had known for decades that he had to change and had talked in private about his drinking problem with a few trusted intimates. In the interest of not wrecking his marriage to Joan, his last chance at love, he limited his alcohol consumption to two drinks a week. Now he was seriously facing his demons without a pen, marker, or brush. I told him I was interested in his work more than his life, but I think he wanted a surrogate grandson to lay him out fully, to be as honest with him as a human as Eisner and Hefner had been with him as an artist.

His daughter Halley had written an Off-Broadway play, I’m Gonna Pray for You So Hard, about a relationship between a young writer and her verbally abusive, alcoholic father. It’s a searing piece—Halley’s powers as a dramatist surpass her father’s. Of course it was him, he told me, and he had no right to question what anyone said about his behavior when he blacked out.

From 2018 to 2020, he contributed a monthly strip to Tablet, entitled American Follies. There’s a symmetry between that strip’s debut and his first appearance in the Voice 62 years before. He had been affected by the Brett Kavanaugh hearings, and he apparently recognized himself in the middle-aged man enraged at anyone who dared question his behavior while under the influence, and who betrayed his loathing by interrupting a female senator with the refrain, “I like beer.”

“Not beer, please! No!” Feiffer writes, alongside a picture of himself in middle-age, suited-up, presumably at Elaine’s. “I was a literary-bohemian drunk. Chardonnay, cabernet, martinis, scotch. For fifty years. Never missing a deadline.” He suggests that Kavanaugh stop blaming everyone but himself, and that if he gave up alcohol, he may even become a better jurist. “What am I saying? Dementia!”

Well Jules could have been a better artist. He won an undeserved Pulitzer Prize in 1986. By that point he was taking cheap shots at campus identitarians and talk show culture, producing the polemics he hated. “The ideas are defensible,” he said when I showed him work from this period, but he was, by his own admission, behaving like a loudmouth at a bar. He had a habit of destroying long-term friendships over minor slights, and who knows what fruitful collaborations he may have enjoyed if not for his thin skin. He had a wealth of material that he mined with embarrassing honesty. But alcohol did not fuel him. If anything, it hindered his work.

From Feiffer 1962. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

From Feiffer 1962. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

No one is simple. Anyone who read his comics, or saw Carnal Knowledge, could tell you that he had troubles with his life as a man. He was a fierce critic of toxic masculinity because he was not himself immune to the disease. And yet, as was not common with members of his gender born in 1929, he had many platonic friendships with women that lasted decades. He was enormous fun and after our first few meetings, genuinely kind, as he often was with younger people he got to know well. He was generous in his way, unafraid to say he admired work that he admired even if it was produced by someone he hated. He could put his ego aside when necessary, particularly at Stony Brook, where he taught hundreds of students who had never heard of him. He was wanting as a father, but he championed Halley, and on his orders his friends attended I’m Gonna Pray for You So Hard.

I have only a secondhand knowledge of his cruelty. I have a firsthand knowledge of his talent for grievance. He had a running list of enemies—critics, editors, family members—stretching all the way back to childhood. (Who, at 85, writes a book called Kill My Mother?) I loved the man dearly, but I didn’t always like him, and whatever he said about his addiction, he knew—everyone knew—that Jules, not alcohol, hurt his loved ones, that Jules, not alcohol, hurt himself. He’ll do okay in the afterlife, but he’ll need a good lawyer, one smart enough not to put him on the stand.

*

My book project lay dormant in Google Drive for a few years, and I wasn’t talking to him as much. He and Joan moved to a house just outside of Cooperstown, which had the clean air necessary for Jules’s health. He worked on his final project, an illustrated autobiography that I hope will prove better than Backing Into Forward, his tendentious 2010 memoir. He told The New York Times last October that he had reached 350 pages.

From Feiffer. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

From Feiffer. Courtesy of Fantagraphics.

That autobiography is probably unnecessary, for Jules had already summarized his life and career in a short monologue that appears in The Ghost Script, the final work in the Kill My Mother trilogy, published in 2018. The book’s protagonist, a shambolic detective named Archie Goldman, suffers a severe beating, which inspires a moment of reflection, as he compares himself to Eisner’s Spirit, the vulnerable superhero who trips on stairs. “Did I win that one?” he asks. “Do I know the difference between losing and winning? Can you live your life without knowing the difference? Is that something important to know?”

Pay attention to that second question, to how Jules switches the words in a familiar phrase, placing the possibility of losing before the possibility of winning. It’s the perfect off-note. Jules was almost 90 when he wrote those words, but he could have ventriloquized them with Bernard, the Dancer, and all his characters who walked a thin line between conformity and rebellion, idiocy and intelligence, loathing and love. In the end, it all came down to how that boy in the Bronx, a child of the Depression and World War II, unaware of the second terrible half of the American century, read and misread his favorite superhero, himself, and everyone he knew.

Paul Morton

Paul Morton is a writer based in Chicago. He has a PhD in Cinema Studies from the University of Washington, for which he wrote a dissertation on the Zagreb School of Animation. His work can be found in Los Angeles Review of Books, The Millions, and Full Stop. His email is paulwilliammorton@gmail.com.