We run ugly, me and Valentine. Pit-stained t-shirts, thrift shop track shorts, stretched out tube socks. Three miles down and Valentine pulls ahead of me, turns and runs backwards, mocking my inability to keep up. It’s been this way always, Valentine out front. I shout for him to slow down so he laughs, runs faster.

Along the path that follows what’s left of the old Mill Creek, we pass all the perfect people wearing their technical tees and matching shorts; their bodies sweatless, their strides graceful. I despise them. They step wide off the path to avoid Valentine as he approaches, seize up on the leashes of their purebred Labradors and whatever-doodles, sensing that my twin brother is not one of them; not anymore.

Four miles and a freaked-out terrier later, he stops at the bend in the Mill Creek where the Great Blue Heron feeds each evening. We sit behind the chain-link fence and watch the bird at the far edge of the water. The sky is striped in sherbet pinks and oranges, and, in the twilight, the heron’s wet wings twinkle like mercury. Valentine tells me the bird is a sign; exactly of what is still unclear but he assures me it will come to him soon, and when it does, it will be epic.

“Apocalyptic?” I ask.

“Maybe,” he says.

I lean against him, our shoulders touching like they must have in the womb. As kids, we played this game where we’d walk around the house back to back, head to head, butt to butt, pretending we were Siamese Twins. He’d steal a butter knife from the kitchen and perform surgery.

“This is an exercise in detachment,” he’d say in a deep professorial voice, imitating our Dad. I would scream theatrically as Valentine sawed away at my arm or leg, as if the tiny ridges of the dull knife were scalpel sharp.

When he stretches out beside me on the grass, I take a closer look. His eyes, dark brown like mine, are glazed with exhaustion. His frizzy braid is nearly dreadlocked, as is his overgrown beard. I can’t recall the last time he’s showered – all we’ve been doing for days is running. His skin that once defied acne is lousy with furious scabs, and somewhere, beneath the Lithium fat and do-not-fuck-with-me scowl is my amazing, gifted brother with enough potential for the both of us—Saint Valentine.

The heron dips her yellow beak in the water and scuttles around. When she lifts her head, there’s a tiny minnow wriggling between her pointed beak. She lowers the fish back into the water, then, suddenly jerks her head upward and swallows the fish whole.

We wait a good long while for her to repeat the show; she never does. Mosquitos party on our sweaty necks as a quarter moon replaces the sun.

“Ready?” he asks, looking at me as if he half recalls who I am, and I want to ask exactly when he stopped taking his meds but he is calming down now and I love this new game of ours.

“Ready,” I say.

“Saint Gregory the Great,” Valentine says.

“Easy. Patron of musicians and teachers. Not a martyr.”

“And Saint Margaret?” he asks.

“Of Scotland or of Virgin?”

“Definitely virgin.”

“Patron of pregnancy and childbirth. Swallowed by a dragon, then beheaded.”

“Very stubborn,” I add as the heron flies away.

“Saint Gall then,” he says.

I tell him what he already knows, that in the ninth century, Gall built a fire deep in the woods of Switzerland, and as he warmed his hands at the flames, a bear charged at him. Yet, the bear, so awed by Gall’s presence, retreated into the woods to gather more firewood and join him beside the fire. The rest of his days, Gall was stalked by the bear.

“Me too,” Valentine whispers. “Me too.”

*

We were born on Valentine’s Day almost nineteen years ago; Valentine first, then me – Corazón. Cory. Every birthday, Mom makes us matching cakes and gives us matching shirts, ignoring that we are not identical twins, me being a girl. On our sixteenth birthday, I got a record player and Valentine got his first stay in the psych ward after I found him preaching from the Book of Revelations on the corner of Hamilton Avenue. When we turned seventeen, we ate slices of red velvet and clacked away on our matching typewriters while Dad walked out for the proverbial ice cream to go with our cakes and never returned. That was also the same year that Dad achieved tenure at the university in – wait for it – Psychiatry.

Mom called it Achieving Torture. We couldn’t disagree.

After Mom was certain Dad wasn’t coming back she painted the house pink – more Pepto-Bismol than adobe –then built a shrine in the front yard. Each morning, she opens the little glass door and lights the pillar candles inside. One for Saint Jude, patron of lost causes and souls. Then Saint Anthony, patron of lost things, and Saint Dymphna, patroness of the mentally ill, and, of course, Saint Valentine, patron of love and, lesser known, of bee keepers and people with epilepsy and those plagued with any type of plague. She believes that devotions to the saints and Tibetan prayer flags and Chimayo dirt from New Mexico and holy water from Lourdes will cure Valentine because she claims mood stabilizers and psychiatrists like Dad are against all of her religions. The shrine also holds a tattered copy of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, the untranslated version. Also plastic yellow roses in a crystal vase. Also a framed photo of Valentine from our junior year in high school. He’s standing on the stage in the auditorium accepting yet another award from the principal. He looks bored and embarrassed and on the verge of slapping the principal’s outstretched hand.

I am not represented in the shrine and, according to Mom, there is no need to pray for me or worship me.

*

How I got to be an expert on the saints is through Valentine. During his second stay in the ward, one of the volunteer nuns gave him The Lives of the Saints for Every Day of the Year by Father Alban Butler; apparently, she thought this would be light reading for her patients. We spent most evenings lying on his bed memorizing their miracles, their arch-enemies, how they were tortured and martyred. Achieving Torture—there are so many methods.

This last time, after Valentine binged on eBay and infomercials with Mom’s credit card and the living room looked like a QVC lost and found, Dad mailed us extra cash to put Valentine in art therapy. Painting, he lectured, would be more productive than memorizing ways to die. Now Valentine paints ex-votos on things I scavenge from the thrift shop where I work part-time. Planks of wood, license plates, cardboard, toilet seats, kitchen chairs. Each ex-voto features Valentine in peril. Stabbed, shot with arrows, impaled on a stake, crushed by train, drowned in a river, struck by lightning, attacked by toothy wolves, abducted by aliens. Always, in the top left corner, he paints the saint that saves him from certain death. The newest one: Valentine shackled to a tree, a swarm of bees spouting from the top of his head. He told me his mind feels like a shaken beehive and the bees are stinging him, only the stings are his thoughts, rapid and unrelenting, and he can’t get the bees organized, like they are queenless or something, and he wishes he could cut a hole in the top of his head to release them.

When I ask how I can help, he shrugs and begins to paint me, hovering over the swarm like a menacing angel.

*

At breakfast, Mom sets a plate of sunnyside-up eggs in front of me and another plate at Valentine’s empty chair. Underneath the eggs a slice of curled bacon smiles at me.

“I’m not twelve anymore,” I say, pulling the bacon mouth into a frown.

From my backpack, I pull out the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders for my Psych 201 class. Dad called it his Daily Source of Miracles, meaning the more disorders available, the more grant money for him. I open the giant book, the pages loosened from the spine due to overuse; in the past month, I’ve diagnosed myself with Malingering, Caffeine Withdrawal, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and Restless Legs Syndrome.

I read aloud to Mom: “A manic episode is a period of at least one week when a person is very high-spirited or irritable in an extreme way, has more energy than usual, runs for miles and miles, paints all the time, has less need for sleep, and exhibits increased risky behavior like running and painting.”

“You shouldn’t read that trash,” she mumbles.

“It’s all right here,” I say, pointing to the page where I’ve logged our running distances in the margins. The pile of unfinished ex-votos in the garage speak for themselves.

She stands over my shoulder and puts her hand on the page near mine. She’s wearing the red kimono Dad gave to her as a Christmas gift the year he left, along with instructions to find her inner geisha girl. The sleeves are frayed, and ribbons of silk slide around her wrists, then fall onto the page. She smells of dish soap and bacon grease and easy Sunday mornings, and I want ask her what she will do if it happens to me, if I will get a shrine too, but I’m not sure I want to hear her answer; she has always loved my brother more.

Mom waves her hand dismissively and pulls the bacon from Valentine’s plate, returns it to the pan on the stove where she’ll keep it warm for him forever.

“He won’t eat today,” I say.

“If only you’d have more faith,” she sighs.

I drag my knife through the middle of the slushy yolk. Valentine and I were two separate eggs once, dizygotic twins, but I know from all the tests we’ve taken that we share fifty percent of our DNA so there’s a fifty-fifty chance that I’ll end up like him some day. Dad says I have nothing to worry about because we are not identical but I can’t be so sure. Sometimes I lie in bed and try to conjure up the mad parade of voices, the angry bees, but they never come.

Valentine walks into the kitchen. His face is flushed and damp with sweat. He grabs a bacon strip from the pan, fresh red paint still dripping from his fingers.

“Things going well in the studio?” Mom asks.

That’s what she calls the garage where he paints. Mom also calls his bipolar creative genius, as in medications ruin his god-given talents.

Valentine high-fives her and she looks at her palm, now speckled red, and smiles blissfully as if she’s bearing the stigmata.

“I’m on top of the world,” he shouts, then glares at me.

Bright rays pour through the kitchen window and I know our run will be very long, very hard today. Valentine twists the knob on the stove until the blue flame blooms under the pan then collapses, over and over.

“I’m painting a mural on the garage.”

“That’s wonderful, honey,” Mom says, her voice milky and warm.

“I think I saw the Virgin Mary in the bathroom tile,” I say.

Mom says nothing, just gently nudges Valentine away from the stove and hands him a forkful of bacon. I dig my nails into my legs, imagine her kimono catching fire. Not even Saint Florian, patron of firefighters, would save her.

“Anyway,” Valentine shouts, irritated I interrupted him. “I’m thinking like Diego Rivera out there. Big statement. More like Man at the Crossroads. None of that calla lily shit.”

Mom looks at him, beaming. “Genius,” she says.

He wraps his hands around my neck and begins to squeeze. “Diego had a twin brother who died.”

Mom snaps the dishtowel against his arm. “No one is dying, mi hijito.”

He lets go of me, talking on as I slip the DSM in my backpack, pull on my running shoes. He lists Rivera’s paintings, the names of his wives, something about Lenin and revolutions and his sentences become fragments as he talks faster and faster, the front door slamming against the wall so hard when he opens it that my eggs quiver.

“Just you wait,” he yells. “They’ll flock here for my work. Like Rivera at La Casa Azul.”

I push my eggs away. They’re too sad with their oozing eyes, without their bacon mouth.

“Our house is pink,” I argue, but Valentine is already gone and Mom only has ears for Valentine.

Outside, a crash. I run to the front door and watch Valentine haul paintings from the garage, scatter them across the lawn.

“You should help your brother,” Mom says.

Already the neighbors are at their windows, peeking around the curtains as Valentine stomps about the yard, rearranges his paintings. I force myself to look at each painting, really look. They are disturbingly good, painfully so, and, in none of them, am I the savior. A bitter taste pushes into my mouth, and I hate my brother a little.

“Cory, it has to be you,” Mom whispers. “There’s no one else.”

I should want to save him again. Stop this like I’ve done before but what I want instead is to be him, feel everything he feels, think everything he thinks, have Mom turn toward me. I’m here, I want to scream but instead I stand there, unable to move, unable to say anything as Mom pushes me aside, waving a crumpled twenty-dollar bill at Valentine.

At school, I sit through Psych 201 half-listening and half-guilty that I’m not at home helping Valentine with his front yard art fair. The class feels like it’s full of students who know what they want to do with their lives already. They sit in packs, fist-bumping and calling each other Bro and Hey Girl and Dude. Valentine was supposed to be in class with me so I’m always turning to my left to whisper something to him about the dreadful professor with his elbow-patched corduroy jacket and Einstein hair but every time I look over the chair is empty and I feel even more lost.

In Spanish 404 where it’s no habla Ingles for fifty-five minutes, the other students itch to get out early because it’s Thirsty Thursday and they can’t wait to take their fake IDs and fake tans and fake laughter to Uncle Woody’s so they can throw up on themselves tomorrow morning. A Dude – or maybe it’s a Bro – sits next to me and spreads his leg so his knee touches mine. He stinks of stale sex and beer.

“Want to come to Uncle Woody’s tonight?” he asks, his face greasy with hangover. He asks it in English which is against class rules.

“Estoy ocupado,” I say.

He cocks his head, thinks, then points toward the door.

“The bathroom is down the hall,” he says.

I imagine bringing him home to Mom and Valentine but then I think there must be more satisfying ways to Achieve Torture.

Now that we’re on a roll, I say, “Me estoy volviendo loca.”

He turns toward me, his vinegar breath hanging between us.

“That’s so hot,” he says. “I dig when girls aren’t afraid to talk about their pussies.”

After class, I go to the registrar’s office and flip through the course catalog, then hand my student ID to the stress-pinched woman behind the desk.

“Let’s drop Spanish and Psych and add Painting and Studio 1,” I say brightly.

She types something into the computer, then shakes her head. “Those are only for Fine Arts majors.”

“You must have my name wrong,” I say. “It’s Valentine. Valentine Corazón Flores.”

*

At the thrift shop, it’s my turn to work the drive-up bins. I pick up a pair of barely-worn tennis shoes. They are my size, bright white with a grey Nike swoosh. I bloom with hope. Valentine’s interest in running has faded now that he’s moved on to painting so I have been running for both of us.

Instead of pitching the shoes in the bin filled with scuffed-up wingtips and worn-out sandals, I slip them in my backpack. Women in pearly-white SUVs unload garbage bags filled with clothes that still have the price tags attached. I give them receipts for tax purposes, inform them that Saint Benedict Joseph Labre, patron of bachelors, rejects, hobos and homeless men thanks them for their generous donations.

Dad rolls up in his Lexus like he does every month and opens the trunk, hands me a box of baby clothes and toys – unwanted things the step-sister I’ve never met has outgrown.

I yank the box from him, inspect a stuffed elephant. Its yellowed tusks hang by threads and its fur is matted with dried spittle.

“Is something wrong?” he asks.

“With this?” I ask, shaking the elephant at him. “It’s beyond gently used. Positively over-loved. I shouldn’t accept it.”

“With you,” he says. He folds his arms, keeps his gaze on me the way he used to when Valentine and I served as his psychological experiments. “Is something wrong with you?”

I shrug, toss the elephant in the bin.

“Is it a boyfriend? School? Any problems there?”

“Not really.”

“Doctor Thatcher said you dropped his class.”

I dump all the pink baby things into the bin, watch them mix with the blue jumpers and onesies. The bin reeks of sour formula and baby powder and purity, and again, a bitter taste collects in my mouth as if I’m going to puke.

“And your brother?”

I swallow hard, push everything back down. When I peeked in the garage last night, half-finished paintings leaned against the walls, on top of the workbench, on the floor—every piece of junk I’d salvaged from the shop shined with wet paint.

“Your son is grand. Brilliant! He thinks he’s Diego Rivera right now.”

“Should I be worried? Your mother doesn’t take this seriously but if he’s delusional—.”

“He’s already sold some paintings,” I say, omitting it was Mom who bought them.

Dad runs his hands down his face. He doesn’t leave so we just stand there staring into the filthy bin until another car pulls up and honks its horn.

“Listen,” he says, “remember how you used to dress up like him to try to fool your teachers. Remember when your mother took you to the doctor because you were convinced you were growing a penis. No one ever wanted you to be like him, Cory. You have other things to offer.”

“Like what?”

Dad frowns, pushes his shiny loafer into the pothole in the pavement.

“Things,” he says, swooping his arms around the parking lot. “If you would just apply yourself, Cory.”

“I’m not paint,” I say. “You apply paint. You apply glue. You apply butter to toast.”

“I can’t help you if you won’t accept help.”

“I’m not the one who needs help, remember? You’re supposed to be helping him, not me.”

Dad opens the car door.

“Cory,” he says and it sounds like sorry. “You don’t love the broken and damaged child more or less because they’re broken and damaged.”

I watch the turn signal blink as he drives away.

“Right,” I say. “You should love her more.”

*

In Studio, my canvas remains blank. While the other students paint, I keep myself busy looking through art books, mixing paints. My easel is at the back of the room and, in front of me, it’s all pointed elbows and hunched shoulders and very serious artistas en el futuro. I pull a small frame from my backpack and set it next to the giant white block of nothing on my easel. Inside the frame is one of Valentine’s ex-votos. Before class, I’d gone to the garage, told Valentine that I needed a hammer and when he didn’t turn away from his work, I grabbed the frame nearest the door and left.

Now, I look at the image for the first time. There’s the Mill Creek filled with green-grey water and the Great Blue Heron dressed in fine robes like the Pope. The sky is angry red instead of blue and, trapped in the heron’s beak is Valentine without a head. Standing next to the bird is me with my brother’s head raised above me like a hat I’m about to wear. Instead of blood, tears drip from Valentine’s head onto my face and shoulders, a black puddle surrounding my feet. Up in the left corner, I immediately recognize Saint Cecelia, organ pipes in hand, her severed head resting on her shoulder. Patron of musicians, she of the stubborn head. Her executioner tried to behead her three times, but still they could not decapitate her so, because of their poor beheading skills, she lived for three more days as people soaked up her blood with cloths and squirreled it away hoping for miracles. I can’t decide whether I’m supposed to be happy or sad that Valentine has given me his head. The professor passes behind me and looks at Valentine’s painting with me.

“You should steal that,” she says. “Good artists imitate and great artists steal.”

I dip my brush in red paint and press the bristles onto the canvas but my hand is shaking and I know whichever way I move, it will be wrong; it is all wrong.

*

On Sunday, I dawdle around the house, avoiding Mom and my homework. I fold laundry, rearrange my running shirts, try my new Nikes on again. They are real running shoes for real runners, and I squish-squish, spring-spring across the linoleum in the kitchen. When I think Valentine has painted long enough, I knock on the garage door. No answer. I knock again, then walk toward him, hitch my Nike-clad foot onto his knee.

“Time to run,” I say all sing-song.

“Go away,” he murmurs.

I do a couple of calf stretches and squats. My legs are muscular now, almost boyish, and, for once, I am sure I can outrun my brother.

“I’m working,” he says.

“Come on,” I whine. “Just this once.”

Valentine rolls his eyes, reluctantly grabs his old Converse. He gets up from the chair slowly, as if each muscle hurts, and he looks old and weary and already beaten.

We run through Spring Grove Cemetery. I feel great. I feel strong and now it’s Valentine trying to keep up. I run like a stiff-legged zombie, lurching toward other visitors yelling “brains, brains.” I hear Valentine behind me, laughing and it is the best sound of all. We are twins again, Valentine y Corazón contra el mundo!

With Valentine far behind, I reach the Mill Creek alone, and pump my fists in the air as I cross my imaginary finish line. In the distance, I see the heron slowly gliding above the creek, her wings arched and taut, her long legs like two sharp arrows as she lands at the edge of the water. The ducks paddle away from her, as if her spot is sacred, and they must give her space. I want her to look up and see me behind the chain-link fence, recognize that, today, I am winning. I spread my arms like wings and think of Saint Francis, how the doves perched on his hands and shoulders, and I wish for the heron to fly to me, sit upon my shoulder but she doesn’t move.

I feel Valentine approach behind me, hear him panting. I begin to turn around to claim my victory but he shoves me backward, pins me against the fence. There are bags under his eyes and a desperate wildness I’ve seen in his face just a few other times. I try to break free but he is enormous, stronger now that something cruel, this unwelcome stranger, is overtaking him. I wait for the punch, for the kick in my gut, the crack of bone that has come when we’ve reached this point before. I wait, chain-metal pressing a honeycomb pattern into my back. I wait, gasping for air as he pins my chest, my arms. I wait for my brother to return to himself. He will not remember this later; he never does. I wait to become someone – anyone – else.

“Saint Juliana,” I squeak. “Patron of chronic suffering. Saint Aloyisius, patron of caregivers.”

He presses harder. “Fuck your stupid games, Cory. Just fuck you.”

And then his face softens and he groans. The sound is tired and ancient and bottomless.

“It’s over. Terminado,” he says.

A familiar spasm of panic creeps through me, a dizzy feeling, like I shouldn’t press him any farther because I don’t want to hear what comes next.

“Don’t talk like that,” I manage to say.

“You’re the death of me,” he says, his voice as thin as the air left in my lungs.

He frees my arms and I grab his hands. They feel so heavy and under the heaviness, I feel the crushing gloom, the long descent into the deep well and, for the first time, it occurs to me that he is trying to protect me from going there with him, that he has not been running away from me but running toward something I will never feel or achieve, and that this is the torture for both of us.

*

When I finally reach home, the door to the garage is half-open. Light leaks onto the driveway. All the houses on the street are dark except ours and the air holds the suggestion of rain. I peek around the door and see Valentine lying on the old couch, his arms measled with bright patches of paint. His hair, unbraided, falls about his shoulders in squally curls. I stand next to him long enough for him to notice my presence in the room, that I am not an illusion. He puts his hands over his face, blue fingerprints dotting his cheeks.

Because I can’t look at my broken brother on the couch any longer, it’s now that I see the piece of wood sitting on the easel. Gazing back at me, two beatific faces, their eyes disproportionately huge, and a tiny pink house at their feet. The figures each have Valentine’s face yet I know they are the martyred twins, Saint Benedict and Scholastica—the first saint story we memorized. Benedict looks most like Valentine, the hair, the beard, the dark eyes. Scholastica, who should have my face, appears nearly the same as Benedict, yet her body is a grotesque Dali jumble of splintered double helixes.

I search for my face, my likeness, among the dismembered bodies and skeletal remains that are stacked against the pink house and find it nowhere until I see the Great Blue Heron, positioned where Valentine usually paints his saint and savior. There I am, hanging from the heron’s talons, limp and dead, a ghostly veil.

I feel something unspool and loosen inside me, like wings unfurling to catch the wind.

Outside, it begins to rain hard. Water sloshes out of the clogged gutters and waterfalls onto Mom’s tomato plants. The candles flicker in the shrine as if they are laughing at the storm.

“It’s perfect,” I say to Valentine. “Really.”

I sit beside my brother on the old couch, the space between us like another living thing.

__________________________________

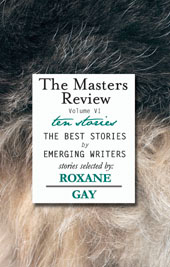

From The Masters Review Volume VI. Used with permission of Masters Review. Copyright © 2017 by Roxane Gay.