This is a Truly Bizarre Way to Write a Novel

Daniel Torday Goes to Great Lengths to Trick Himself Into Finishing

I’m a tinkerer by temperament. My most frequent nerdy joke with my writing students is that if you sat me down at a computer every day for a year when I was 22 and let me have at it, a year later I’d have come up with Pound’s two-line poem “In a Station of the Metro,” only it’d be shorter. So in my process in writing longer, in writing novels, I’ve had to trick myself out of tinkering. It’s led to a process that sounds batshit crazy when I describe it to people, but I’m deep into working on my fourth book so I guess it’s at least worked for a time.

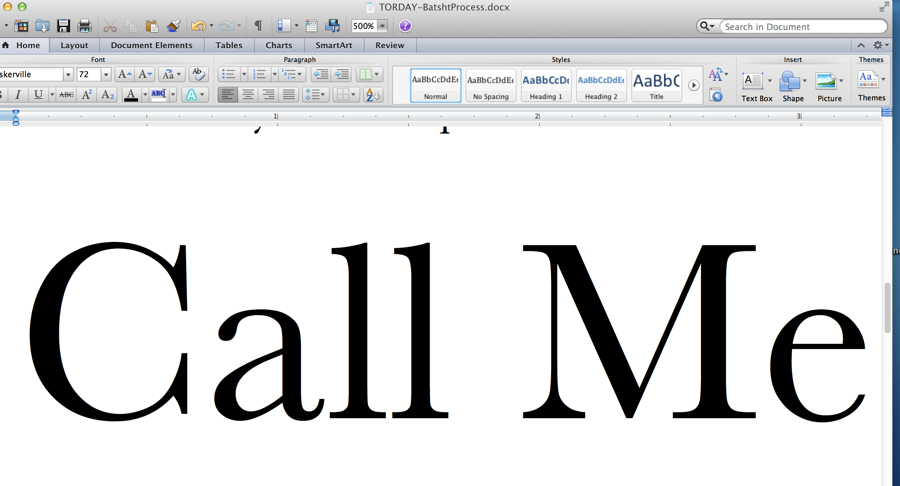

At the beginning of each project, I take the Word file I’m working on and put the point size at 72. I select the percentage view at top and put it at 500 percent. This makes it so that I can only see a couple of letters onscreen, like this:

And then I just type forward. For as long as I can allow myself. Which for a novel can be months. A year, even.

Now look, I get it. This sounds nutso. I’ll confess that I often can only last a month or so before I have to go back, put my file back to 12-point font (Baskerville, obvi) and 150 percent view. But while I’m working, this process somehow games a whole bunch of the hardest aspects of writing a novel: it gets me to stop tinkering. It keeps me from worrying about the quality of what’s come before (I can’t even see what’s come before!) and allows me just to forge ahead. Forging ahead means accruing words. And perhaps the only definition we can hold the novel to is that it is a drastic, almost unnatural, accrual of words.

I’d also be deeply irresponsible not to share that after this process, I’m an arduous and rules-based reviser. My rules probably sound less crazy than, well, rigid. I do not allow myself to do any cutting on screen. On-screen I’m a shark—I can only swim forward, and I’ll eat anything that smells of blood. I cannot swim backward. Then I print out, and in the case of this process, I only print once I feel done. After I print I pick up a pen and I’m the opposite of a shark (a sloth with a pen? carpenter ant with a day job working as a sculptor?): I can only cut, and I can only write new words if they fit between double-spaced lines or in the margins. Now that’s not to say I never write new words on paper, but in margins and on the blank back of the page it’s not possible to write more than, say, 300 new words. And I try not to. But then sometimes I do. When I’m inputting changes I’m writing again, and it can lead to new material. This is all a little more mundane, but the residue of the weird murk of writing while only being able to see a handful of letters at a time for months pervades every move.

Randall Jarrell defined the novel as “a long prose fiction with something wrong with it.” Once we accept that definition as being more than pithy phrase-making it’s actually quite useful. Novel drafts are by definition going to have lots wrong with them. In fact I’ve come to think that novels succeed when they create and then solve big, intractable problems. That’s the gambit. It’s like being a ski jumper. No one cheers when a ski jumper takes off. They cheer when she lands successfully. They comprehend clearly what the problem was: the ski jumper wanted, first and foremost, to not die. The novelist can’t solve problems until there are problems to solve on the page. I’ve come to believe you can actually push the process by accepting those things, creating them even, and dealing with them later. With my most new book, Boomer1, this meant dealing with three separate voices, which the book alternates between a half-dozen times over 350 pages. But again this crazy process somehow addressed it—rather than worry about the syntax or diction or something technical in what distinguished the voices, I just listened to them. Typed. Listened. Typed. I couldn’t go back and scrutinize.

“Novel drafts are by definition going to have lots wrong with them. In fact I’ve come to think that novels succeed when they create and then solve big, intractable problems.”All of which might sound a little down-in-the-dirt, and facile, and a lot unsexy. But I suspect there’s something deeper at work: my experience of reading great novels is that they give the feeling that there’s a whole world past the words on the page. And in a way that’s the hard part: forcing yourself to imagine that world fully, and knowing it. So the less you focus on the language in front of you as you proceed, the more we feel it as readers. That’s not to say the language can’t be every bit as beautiful as in a short story, can’t sound like Housekeeping or Lolita or Beloved, Faulkner or Jesmyn Ward or Paul Beatty. But those books and writers sound like that and they evoke the worlds they evoke. There’s a lot that’s not yet on the page, that feels as if it exists elsewhere. Anything you can do as a novelist to force that feeling—whether it’s wholly organic or not—will grant the reader that feeling, too. Writing a lot and cutting a lot does it, and the process I’m describing leads to both. The reader doesn’t think, Huh, he cut pages. She feels, there’s a lot more to this story than what’s on the page.

Now here’s the part where I confess I probably do this less often than I think I do. I’m neck deep in work on a new novel now and I’m finding myself doing something new: just thinking a lot about the book, and not writing at all. Thinking about it while I’m running, while I’m cooking, while I’m in the shower. Holding as much language in my head as possible for as long as possible, and then letting it land on the page a little more naturally. To this new version of myself, the old crazy process isn’t all that useful. It’s crazy, but in a new way. Maybe I got here, now, by moving on from that. And maybe that’s exactly what a writing process is good for. To have something to stray from. And then, when in doubt: 72-point font. 500 percent view. Get typing.