The day is white; its glare burns if you look straight at the sky. The air is still. An angel perches with folded wings on one of the mausoleums, pitch‑black against the incandescent clouds. It looks like a predator, a bird of prey. Like it could swoop down from there if the stone weren’t holding it in place. Years ago, the fever itself could have been represented that way—a dark angel silhouetted against a sky of ash.

No one seems to notice it. A throng of camera‑wielding tourists descends on the cemetery; to them, the statues are merely stone. An identical scene unfolds every day, though the tourists change. They don’t shout or laugh, they don’t raise their voices. They show respect for something they can’t quite name while making their way among the tombs with measured interest. They pause at the historic figures they recognize—presidents, writers, big names—and read their plaques like schoolchildren competing for a prize. Or they let themselves be guided through the labyrinth by appealing shapes: wings outstretched in a balletic gesture, hands gently cupping a face, overcoming the rigidity of stone.

Sometimes they get lost in the alleys that divide the tombs into blocks, replicating the structure of a city. The cemetery is small, but the diagonal walkways that radiate outward from the entrance disorient visitors and lead them into unexpected corners. So does the fact that they’re looking upward as they pass through the shadows cast by statues like La Dolorosa, figures that cover their faces to hide their suffering, but ultimately seem to hide something far worse.

This is the oldest cemetery in the city, the only one that still offers death the elegance of another time. A dream in marble, built with the money of wealthy families. Only those able to pay for the right to poetry in death are here; for everyone else, common graves or bare stone signal, definitively, their insignificance in life. This afternoon, I walk along the gray paving stones and wonder where I’ll be buried, whether I’ll rot slowly underground or in one of those neatly stacked niches way up high, where a single wilted carnation bears witness to the fleeting nature of memory. But the visitors seem unfazed—delighted, even—as they aim their cameras at this plaque bearing a famous name or that opulent tomb.

This abstraction is made possible by the absence of any smell. Because so many precautions are taken to keep putrefaction from escaping the vaults in the form of liquids or gases, this is the only cemetery in the city not permeated by the rancid, sweet, offensive stench of bodies slowly decomposing. Flowers never manage to cover that smell. It gets in your nose, and you feel like it will stay there forever. It’s more insidious than excrement, than trash—maybe because if you weren’t aware of its macabre origin, you might think it was perfume. Only the flesh knows horror; bones, once clean, might as well be fossils, pieces of wood, curiosities. It’s flesh that has been keeping me up at night.

I’ve been visiting this cemetery compulsively for the past few weeks. This time, I’m trying to conjure—by day and accompanied by my son—a disturbing memory. Santiago runs ahead of me and has no idea what I’m thinking. He’s five years old; at first, he fell in love with this labyrinthian cemetery, this miniature city, but then he asked me to stop bringing him here. I told him that today was the last time. I promised to buy him a present if he came with me, and he agreed. Now he’s chasing an imaginary skeleton he has named Juan. He searches among the tombs for the one with a skull and crossbones etched into its glass doors, believing a pirate is buried inside.

He wants to play hide‑and‑seek and yelps with excitement, but I tell him firmly that he can’t shout or run here. Because he might crash into someone, because one should be respectful wherever people are buried. I don’t know how, but he understands. He’s young, but he can sense a difference in the air here, like in museums and churches. Whenever I take him to the Museo de Bellas Artes or the cathedral, I show him—by drawing a finger to my lips before we step inside—that some places are meant to be entered in silence, on tiptoe.

We choose a different path from the groups of tourists following their guides at a crawl and quickly lose ourselves in the far reaches of the cemetery. Santi is wearing red pants, the brightest thing in the whole place, and he’s running again, amid all the marble and granite. Suddenly, he stops. He stands frozen before the tall statue of a woman who rests her sword on the ground in a gesture of defeat; he needs to tilt his head all the way back to see her fully. Then he snaps out of his trance and runs on. He reaches a tomb a bit farther down the alley and grabs the knocker hanging from the mouth of a bronze lion with both hands, trying to pull the door open. I tell him to stop. He obeys—even if he doesn’t exactly know what I’m protecting him from—then runs off again to kneel beside a glass opening on the side of a mausoleum and point inside. I go over to look in with him. He peers into the darkness and asks me if the smallest coffins are for babies. Not always, I say, sometimes after people have been buried a long time, only their bones are left and they can be put in a smaller casket. I don’t want to tell him that sometimes bodies are put into ovens and reduced to ash.

When he finally finds the tomb with the skull and crossbones, he sits on the front steps and asks me to take his picture. Sometimes I wonder if it’s all right for him to have death flung at him like this, at such a young age. If I should try harder to hide it from him. On the other hand, we never invited death into our home, and yet, there it was.

We walk through the cemetery and I try to keep one eye on him as I allow my attention to linger on whatever jumps out at me. I pause at the tombs that have cracks in them, fissures. Everything I see is broken. Wrought‑iron French doors missing panes of glass, barely held shut by a hastily slung chain. Mausoleums where the floor has given out and you can see the rows of caskets on their shelves down in the crypt. Caskets with their lids pushed aside or destroyed, as if an axe—not only time—had laid into them. This is, in some cases, precisely what has happened. I imagine the furtive presence of those living bodies at night, amid whispers, half concealed by the dark, as they search the abandoned tombs for something they can sell.

I’m searching for something, too; now and then, I wonder if I brought Santiago with me so I wouldn’t find it. As if he were a talisman. I call him over to show him the caskets inside one mausoleum with broken glass panes. Weeds sprout from the cracks in the floor, as if in the future the cemetery’s gray scale, its stone solidity, would be overpowered by a force emerging from deep in the earth. Inside the mausoleum, the brown paint on the walls is cracked and a plant climbs upward along a crevice. It smells of damp. A long bone is visible through the broken lid on one casket, maybe a humerus or a tibia; it is completely clean of flesh, the way bones look after they’ve been chewed and licked for hours by a dog, but without the shine.

__________________________________

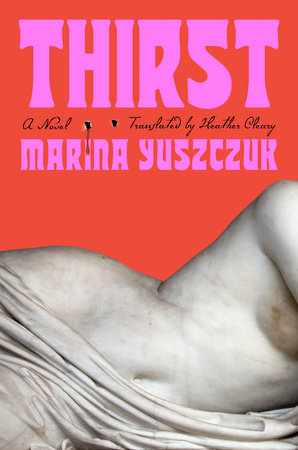

From Thirst by Marina Yuszczuk (trans. Heather Cleary). Used with permission of the publisher, Dutton. Copyright © 2024 by Marina Yuszczuk, translation copyright © 2024 by Heather Cleary.