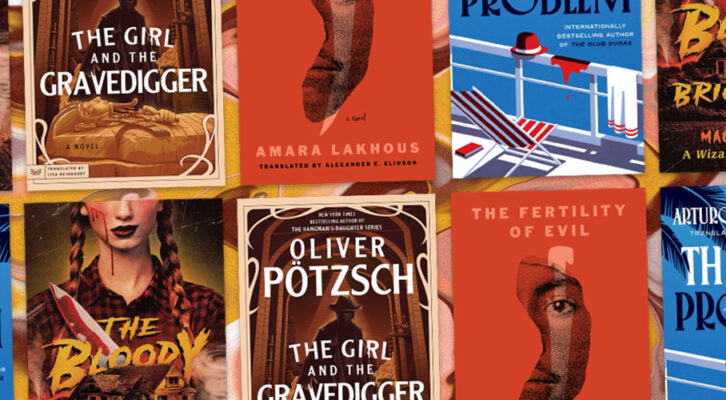

These are our favorite New Directions books from their 85 (!) years of publishing.

This month, New Directions is celebrating their 85th birthday; the festivities will kick off this week with “a night of poetry and remembrances” featuring Will Alexander, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Susan Howe, Sylvia Legris, Nathaniel Mackey, Fred Moten, Michael Palmer, Elliot Weinberger, Nathaniel Tarn, and other guests. The venerable press was founded in 1936 by Harvard sophomore James Laughlin, apparently because Ezra Pound advised him to “do something useful” after school. The original New Directions publications were anthologies of new writing; now the press focuses on introducing contemporary international writers to American readers, publishing new work by experimental American writers, and of course, putting out gorgeous reissues of older texts.

To celebrate 85 years of New Directions, each member of the Lit Hub staff wrote a little bit about one of their favorite New Directions books (we spent no small amount of time on Slack thinking/fighting about who would get to write about what). Of course, this is only scratching the surface of their incredible list, but you’ve got to start somewhere:

Helen DeWitt, The Last Samurai

Everyone whose opinions I respected had been recommending The Last Samurai to me for years, but none of them ever gave me the vaguest idea of its plot. (For longer than I care to admit, I assumed it was the source text for the Tom Cruise movie of the same name. In fact, DeWitt’s original title was The Seventh Samurai, but she was forced to change it for legal reasons.) The top-line plot summary—after an isolated childhood shaped by Ancient Greek lessons and repeat viewings of Kurosawa’s The Last Samurai, the (extremely) precocious son of a single mother sets out to find his birth father—doesn’t hint at the novel’s brilliance. It’s idiosyncratic and fragmented, but somehow still inviting in its strangeness. It’s enormously funny. It makes you reconsider the possibilities of fiction, of pages. (And if you finish it the day before you give birth, as I did, it might give you some ideas about early childhood education that were likely not DeWitt’s intended takeaway.) –Jessie Gaynor, Senior Editor

W.G. Sebald, tr. Michael Hulse, The Rings of Saturn

I remember reading The Rings of Saturn for the first time, and after only a few pages stopping, thrilled, thinking to myself, Wait . . . you can do this? I didn’t see any reason for it to be as propulsive as it was: there’s no plot, and barely any recurring characters. It is, broadly, a novel about a man walking around England’s Suffolk and thinking about things related to the history of the places he visits. But really, of course, it is a novel about a mind—and at the risk of being too precious, a novel about mind, in general. It is witty, elegiac, and precise; it is a novel for the curious, and for those who like to learn things as they read, and for those who don’t need every connection handed to them on a platter. (That feels old-fashioned now, alas.) It was my gateway into Sebald—soon I would also particularly love The Emigrants and Austerlitz—and I have never looked back; I re-read it now once a year, and find new things inside of it every time I do. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Anne Carson, Glass, Irony & God

New Directions has been a home for Anne Carson’s work for a long time now, so choosing a single book from her stunning catalogue is, to say the least, difficult. Carson’s work itself defies description: she is completely unlike any other writer, and nearly every line she composes presents twists of language that challenge and animate me as a reader. Glass, Irony & God is no different; in pieces like “The Glass Essay,” “The Fall of Rome” and “The Gender of Sound,” Carson brings the shock of inventive contemporary language to bear on her deep study and understanding of ancient ideas. Each of the pieces in this collection is unforgettable and worth returning to again and again. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

[Also, Nox!!! –ET]

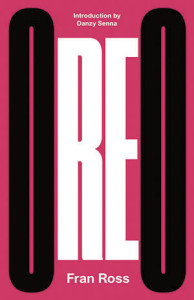

Fran Ross, Oreo

Fran Ross’s underappreciated 1974 satire centers on Christine Clark, a biracial Black girl from Philadelphia in search of her Jewish father. In a 2018 review for The Guardian, Marlon James wrote: “Oreo laughs in the face of the American one-drop ideal of whiteness that produces Oreos in the first place.” Indeed, Ross’s humorous novel mocks the absurdity of racial “purity” while recognizing the very real systems that elevate and sustain the institution of whiteness. Ross’s use of language mimics an elaborate display of code switching, showcasing the ability to effortlessly slip in and out of various allusions, idioms, myths, vernaculars, and cultural touchstones. Christine’s ability to improvise and impersonate comes in handy throughout her quest for self-enlightenment. This skill speaks to the muliticiplity of her identity as a woman who lives in a world that measures racial “authenticity” in rigid percentages. Published two years before Alex Haley’s Roots, Oreo debuted to little fanfare and went out of print for years. Fortunately, the novel has undergone a recent resurrection, ensuring the continued life of Ross’s only published book. –Vanessa Willoughby, Assistant Editor

Fleur Jaeggy, Sweet Days Of Discipline

Translated from the Italian by Tim Parks, Sweet Days of Discipline is Fleur Jaeggy’s unsettling account of girl-on-girl obsession at a Swiss boarding school. The fourteen-year-old narrator is fixated on a withholding girl, Frédérique: desperately trying to intellectually impress her, practicing her handwriting to match Frédérique’s. All the desire and violence of growing up is misdirected into the school’s restrictive routines. Explaining the girls’ clothes, folded with care in their cupboards: “We were fetishists.” With cold, crisp prose, Jaeggy captures the cruelties, snap judgments and mental agonies of childhood—all with death waiting at the end. “We imagined the world. What else can we imagine now if not our own deaths? The bell rings and it’s all over.” At 105 pages, it’s a tighter Virgin Suicides, without all the boys smudging the lens. –Walker Caplan, Staff Writer

Nathanael West, Miss Lonelyhearts & The Day of the Locust

What if the Great American Novel was in fact two novellas, grimly linked by their refusal to accept the American Dream as anything other than a waking nightmare? Though some have called Nathanael West’s dark double-feature (reissued as such by New Directions in 1969) the literary heir to The Great Gatsby it is, more precisely, the spiritual forebear of everything that came after.

Miss Lonelyhearts, the story of a newspaper “advice” columnist slowly consumed by the mundane tragedies of those lonely souls he encounters via the US mail, reads now like a gloss of the most pitiable aspects of social media: turns out the worst parts of us, that revel in the public performance of private pain, have always been there. The Day of the Locust, about a young designer whose soul is gradually being replaced by the slow poison of Hollywood cynicism, takes things even further as hypocritical moral outrage gives way to a brand of mob violence all too familiar to anyone reading in 2021.

The particular degradations we think are unique to Twitter or reality tv or, say, American politics c. 2021, are all right here in West’s writing, which is more prophetic than it is prescient: these novellas are not written in warning, but rather as candid snapshots of the doom that’s been with us from the start.

Thanks New Directions! –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

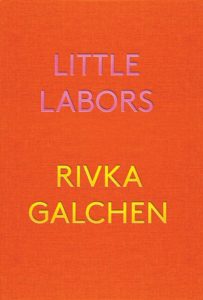

Rivka Galchen, Little Labors

There is so much to love about Little Labors: Rivka Galchen’s sly humor, the lyrical vignettes that poke and prod at everything around her, from a 47 Ronin movie poster she passes on walks with her infant to meditations on the newly released Guantanamo Bay photos and the ratio of successful writers to their number of children. Her musings on taking care of a baby—referred to for most of the book as a puma—strike me, a non-parent, as the most honest thing I’ve ever read about motherhood, in that they capture both the mundanity and the supernaturalness of the task. Truly a delight, and one that can be read in a single sitting or during precious spare moments of time. (Plus, that cover gives me life.) –Eliza Smith, Audience Development Editor

Denise Levertov, The Collected Poems of Denise Levertov

I first came across Denise Levertov in my deep poetry awakening in college (you all know the one) and have remained struck ever since. Her work felt like a recognition of all the things I’d been grappling with in writing: feeling tired of writing only of darkness, but how empty writing about happiness could sometimes feel, like a picture of something, but perhaps not the full picture. One line of hers I think of daily: “this is the knowledge that jostles for space / in our bodies along with all we / go on knowing of joy, of love.” She’s speaking of war in this poem, of cruelty and violence, and how life itself is an experiment in having to hold many opposites, and pieces, of both joy and brutality, dark and light. I’m flagging her poetry, but everything by Levertov is necessary and unique in its own way. There’s also a great book of letters between her and her longtime friend William Carlos Williams, another New Directions author, and another favorite of mine, Tesserae, is an example of memoir being anything you want it to be. It’s made up of fragments/shards of memories, the word “tesserae” referring to the the glass that makes up a mosaic, depicting life in its most raw and unfinished, while somehow adding up to a complete whole. –Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

Fernanda Melchor, tr. Sophie Hughes, Hurricane Season

Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season begins with a group of children finding the dead body of a Witch—and it only gets more disturbing from here. This dark gem of a novel, beautifully translated by Sophie Hughes, is an attempt to understand the murder. It is also a warning about the stories we tell and the ways we make monsters of people. Told from alternating perspectives, this sinister story paints a picture of a small town and the cruelties its inhabitants inflict on one another. The experience of reading this novel is like walking into a dark house and having all the rooms shape-shift in front of your very eyes. The more you find out about each character, the bigger and darker the house seems. And then the floor falls out from under you. What adds to this propulsive feeling is the way Fernanda Melchor wields language. Every sentence is a torrent. Hurricane Season is a force to be reckoned with. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

Rachel Ingalls, Mrs. Caliban

I think about Mrs. Caliban—Rachel Ingalls’ dreamlike and devastating 1982 novella about a grieving housewife in a broken marriage who begins a passionate affair with a 6-foot-7-inch fugitive humanoid sea creature named Larry—about once a week. Anytime somebody mentions genre-bending fiction or unreliable narrators or extramarital sexual awakenings or classified government experiments or shitty husbands or misunderstood movie monsters or the quiet devastation of mid century American suburbia or Señor Frog’s, I think about Mrs. Caliban. It’s a lean, strange, hallucinatory masterpiece—a tender, almost fairytale romance suffused with an intoxicating miasma of surrealist dread. Someday, when my ship comes in, I’m going to buy 100,000 copies of this book and journey across America, planting them in coffee shops and bar snugs and aquariums like a deranged Ingallsian Johnny Appleseed. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor in Chief

Natalia Ginzburg, tr. Minna Proctor, Happiness, as Such

Though our assignment was to pick a single title, I have to thank New Directions for introducing me to Natalia Ginzburg, a new lifelong favorite, starting with this reissue and new translation of her 1973 novel Happiness, as Such (originally published as Caro Michele). The largely epistolary story circles around Michele, a political dissident who’s fled for England, leaving behind a former girlfriend (who also happens to be pregnant), a depressed mother, an older sister (who mails his Kant books and identity documents on request), and close friend/sometimes lover Oswald. What I’ve since learned about Ginzburg in reading her other novels—including The Dry Heart and the just-released Voices in the Evening—is that no one does comedy-meets-melancholy quite like her. Consider me in your debt, New Directions! –Eliza Smith, Audience Development Editor

Jenny Erpenbeck, tr. Susan Bernofsky, Visitation

What a joy to discover Jenny Erpenbeck! Like many works in New Directions’ list, and work in translation in general, I came to Erpenbeck out of order, reading her later novel Go, Went, Gone before The End of Days, and only recently 2010’s Visitation. But in whatever way, whatever order, one finds oneself immersed in the crisp, perfect prose of her novels, you will thank brilliant translator Susan Bernofsky for bringing Jenny Erpenbeck into your life. Visitation, in particular, is the kind of short, sharp, perfectly formed work that takes your breath away. It centers on a great house overlooking a lake in Brandenburg, East Germany, and its succession of owners: a Jewish family forced to flee with the rise of the Third Reich, the architect who takes it from them, the Russian major who subsequently commandeers it, and the exiles returned from Siberia who reclaim it before its inevitable resale. In the successive arrivals and departures of the occupants, each witnessed by a gardener whose enduring presence lightly binds their narratives together, the novel distills the sweeping movements and horrors of twentieth century history into oftentimes unbearably sympathetic human form. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor