There's No Place Like Home—Except the Beach: Visual Stories of Montauk, New York

Rufus Wainwright and Jörn Weisbrodt: "The beach is the divide between one world, the dry, and another, the wet. It is a mythical place of transformation."

Montauk calls itself “The End,” but it never seems to reach an endpoint. Quite the opposite. It is in a continuous state of beginning, starting over and over again but never really coming to a conclusion of what it actually is. All the dreams humankind has put on it seem to end before they are realized. Constantly in flux, like its shoreline that gets shaped by storms and the tide, Montauk seems never to fully realize itself. It is on a different path than East Hampton or other Hampton villages. Those locales solidify their status as fortresses of wealth as they suck up ever more upper-class families with growing appetites for local produce and wine, flying jets and helicopters out to $5,000-per-square-foot homes. East Hampton and Southampton are ends in themselves. The Maidstone Club, Further Lane, and Gin Lane are endpoints of a luxurious dream in those towns. Montauk is different. It is more fluid, literally.

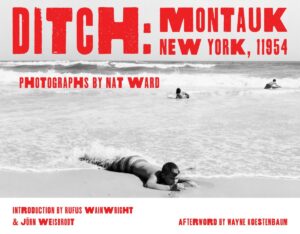

Montauk is a hamlet on the easternmost tip of the south shore of Long Island. 4,000 people call it their home year-round, and 40,000 people visit in the summer, in large part attracted by its natural beauty and beaches. Ditch Plains is Montauk’s most famous beach, although most likely not its most beautiful. The way the rocky shore slopes gently into the ocean creates long rolling waves ideal for surfers.

Montauk’s history is paved with unrealized dreams and reinvention. The name comes from the Montaukett tribe, who lived in the area before white settlers arrived in the 17th century. After a war with another tribe in 1653, the Montauketts were severely weakened and ravaged by smallpox. They sold the areas of today’s Napeague and Montauk to white settlers in return for food and were allowed to remain on parts of the sold land. At the end of the 19th century, Arthur Benson bought 10,000 acres of the East End and Big Reed Pond where, after the 1653 war, the remaining Montauketts lived, and he asked Stanford White to design the first homes at Montauk Point. The legitimacy of Benson’s transaction is still contested in court by the tribe today.

A railway connecting Montauk to New York City was built, as was a dock for ocean liners, to cut the travel time from London to New York City by a day. The idea was that passengers disembarking at Montauk and heading to New York City could travel the rest of the way by train. Unfortunately, the plan did not work out, and the military took over the land to quarantine soldiers returning from the Spanish-American war. After the First World War, Robert Moses began condemning the Benson land to establish two major state parks on either end of Montauk. This decision set Montauk radically apart from the rest of the South Fork, which was primarily used as agricultural land with no state parks.

A couple of years later, Carl Fisher bought most of the East End of Long Island and dreamed of developing it into the Miami of the North, another dream for Montauk that was shattered, this time by the great Wall Street crash of 1929. The Great Hurricane of 1938 then turned Montauk temporarily into an island. The Second World War brought a fresh wave of military investment and presence. Disguised as a fishing village, Camp Hero was established as a coastal defense station against German submarines. Rumors of teleportation and time travel experiments carried out at Camp Hero under the code name “The Montauk Project” have circulated to this day and inspired one of the 21st century’s most famous TV shows, Stranger Things.

In the ’60s, over 200 Leisurama homes, ready-made second homes for hardworking lower and middle-class families, were built in Montauk and started Montauk’s ascent as the dream beach location for American suburbanites. At the same time, global pop art and rock and roll royalty took refuge in Montauk, as the rest of the Hamptons was already fully established as a playground of the wealthy Manhattan elite. In Montauk, to this day, everything and everyone collides, from hip surfers to local fishermen to middle-class families, trailer park inhabitants, and Mick Jagger.

There is always the danger another hurricane could destroy downtown Montauk altogether or tear it off from Long Island once more. This is a place where people can dream big or small, where dreams end, and new ones emerge. There is room for everyone and the dreams they come with. There is no dictatorship of privet hedge as in the rest of the Hamptons. But here, whether you are a resident of a small motel room on the beach, live in a trailer off Ditch Plains, inherited a prefab “Leisurama” from your parents, or tore down a ’50s kit house and built a six-bedroom mansion with a helicopter pad, Montauk is the home for all those dreams, and its beaches are the living room. This is where Nat Ward’s images start their enchanting existence.

Constantly in flux, like its shoreline that gets shaped by storms and the tide, Montauk seems never to fully realize itself.

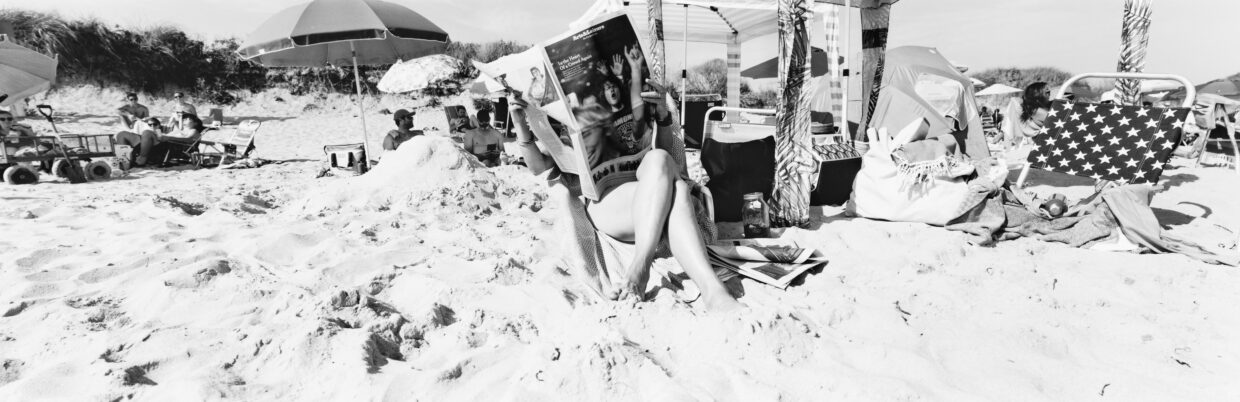

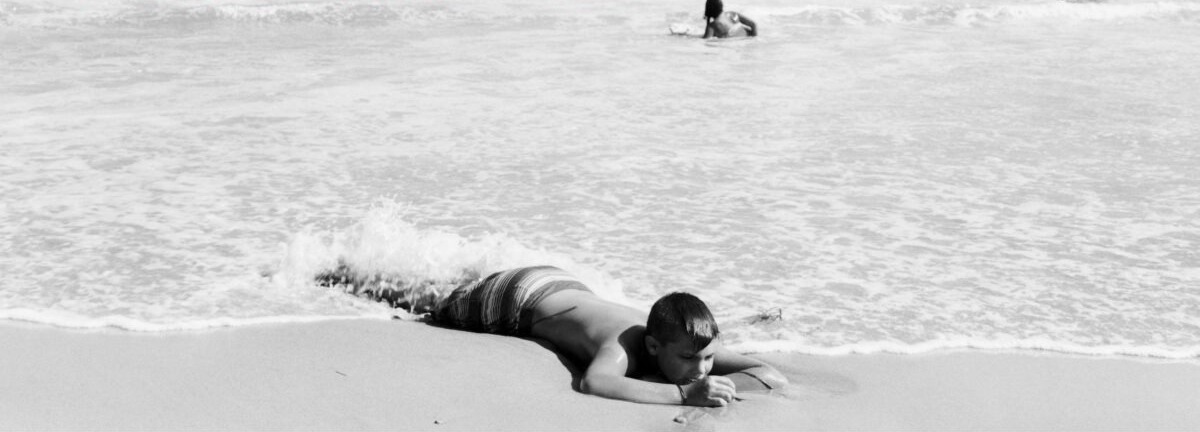

There is no place like home, except the beach. We love the beach just as much as we love our homes. Simply put, the beach is a home to us. The only difference between our private domestic space and the beach is that there are no walls on the shore. But we still behave as though we were at home. Nat Ward’s images, taken mainly at Ditch Plains, Montauk’s famous surf beach, seem to prove that. People love making the beach their domicile, exhibiting the very intimate social behavior normally reserved for one’s own four walls. People decorate their spot on the beach with towels, umbrellas, surfboards, chairs, coolers, and more, temporarily recreating the basics of an entire human household on a vast crystalline expanse. People build castles, fortresses, and walls behind which to escape the winds. They construct fires, ditches, and temporary graves. They lie half naked in the sun, on top of each other, sprawled out on the warm silicon dioxide exposing cleavages, armpits, and butt cracks.

When you watch real estate shows, it is fascinating how much value is devoted to privacy in your backyard or the house itself. We do everything and spend lots of money to prevent strangers from being able to see us in intimate situations, sleeping in our beds, playing in the backyard, sprawled out on our couch half-dressed, lounging by the pool, or taking a shower. Except, when we are at the beach, we love doing all these things in total public view and more. There is no shame, no prudishness on the beach, a place where you have to bare yourself. You want to tan? You have to be naked.

Nat Ward’s images are highly composed snapshots of the intricate social life of the beach. They are not static images, but there is a mysterious before and after that oscillates around the images, a story that could be told. The barking dog in the sun on his owner’s beach towel who might have gone in the water or is clearly doing something somewhere away from him that stresses the little guy out. The teenager with a Top Gun jet kite in his hand that is just about to lift off or crash. The three kids sitting on the sandy perimeter of the round shadow of a beach umbrella that is not in the picture listening to someone outside of the frame talking to them while one slightly older kid is attempting somewhat of a down-dog yoga pose. The matriarch of a family in a Botticelli pose while a male member of her clan, perhaps her husband or brother-in-law with a beer in his hand, looks at her boobs and her hands as they stroke through her slightly wet curly hair while maybe her daughter takes a quick break from her phone, and other relatives are looking in their cooler for a cold beverage or food.

All these images tell naked, unedited stories of who we are as human beings, social creatures, and families. These are stories that you cannot tell anywhere else except on the beach because rarely are we less inhibited. Everything on the beach is in the open, drama is tangible, skin is touchable. On the beach, we are all dirty. We all lie in the sand, walk in the sand, and cleanse ourselves as we bathe in the ocean, only to get dirty and sweaty again. The beach is the divide between one world, the dry, and another, the wet. It is a mythical place of transformation.

The beach becomes a stage for human behavior, and Nat Ward’s images create the proscenium arch for these domestic scenes. The people in his photos are aware that they are being photographed. Sometimes they pose for the picture, and sometimes they seem to ignore the camera. Nat Ward is not a voyeur who hides his camera under a towel to take secretive snapshots of unaware subjects. He behaves like a documentarian, outfitted with a large camera that draws its own attention, and thus cannot be mistaken for a casual hobby photographer. Like David Attenborough and his camera team filming wild animals, Nat Ward is transparent about what he does—only his wild animals are people who consciously frolic and mull around in front of his lens.

A Shakespearian quote, or adaption of a Shakespearian quote, comes to mind to express who we are:

All the world is a beach, and all men and women merely players in the sand.

__________________________________

From Ditch: Montauk, New York, 11954 by Nat Ward. Introduction by Rufus Wainwright and Jörn Weisbrodt. Afterword by Wayne Koestenbaum. Copyright © 2025. Available from Powerhouse Books.

The Montauk Historical Society is honored to invite the public back to the Second House Museum for the first time since 2013 to experience a remarkable photographic exhibition on May 24th from 6-8 pm: “Ditch: Montauk, NY 11954″ by Nat Ward. It’s free and open to all. Donations are welcome.

Rufus Wainwright and Jörn Weisbrodt

Praised by The New York Times for his “genuine originality,” Rufus Wainwright has established himself as one of the great male vocalists, songwriters, and composers of his generation. The New York-born, Montreal-raised singer-songwriter has released ten studio albums to date, three DVDs, and three live albums including the Grammy nominated Rufus Does Judy at Carnegie Hall. He has collaborated with artists such as Elton John, Burt Bacharach, Miley Cyrus, David Byrne, Boy George, Joni Mitchell, Pet Shop Boys, Heart, Carly Rae Jepsen, Robbie Williams, Jessye Norman, Billy Joel, Paul Simon, Sting, Chaka Khan, Brandi Carlile, John Legend, Anohni and producer Mark Ronson, among many others. He has written two operas and numerous songs for movies and TV.

Jorn Weisbrodt was born in Hamburg on January 26, 1973. He studied opera directing at the music conservatory “Hanns Eisler” in Berlin. He is married to Rufus Wainwright and currently manages his career and produces his work. Until 2016 he served as the artistic adviser to the Music Center in Los Angeles where he produced a large birthday concert for Joni’ Mitchell’s 75th birthday that was released as an album and movie across the globe. He was also the inaugural artistic director of ALL ARTS, WNET’s 24 hour cultural TV channel and online platform. Between 2012 and 2016 he was the Artistic Director of the Luminato Festival in Toronto where he commissioned and produced new works with artists such as Marina Abramovic, Lemi Ponifasio, Kid Koala, Dana Gingras, Ohad Naharin, and R. Murray Schafer. Before this appointment he was working as the executive director of RW Work Ltd. representing and managing the work of Robert Wilson and as the director of The Watermill Center—a laboratory for Performance founded by Robert Wilson in New York. He has been instrumental in producing productions such as “The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic” and the worldwide tour and revival of Robert Wilson’s and Philip Glass’ opera Einstein on the Beach. For The Watermill Center he has established partnerships with the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Baryshnikov Arts Center, Kampnagel Hamburg, the Donaufestival in Krems, the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, Performa, the Purnati Arts Center in Indonesia, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Columbia University among others.