There is a bell hooks Book for Every Season of Life

Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah on the Liberatory Possibilities of Sexual Experience

I first came across the work of bell hooks when I was nineteen years old. The year was 1997, and I had just moved from Ghana to the United Kingdom to study for a degree in Communications. For the first time in my life, I was living separately from my close-knit nuclear family, and while on one hand I was exhilarated by my newfound independence, on the other I felt challenged by the society I was now living in. In my imagination, the U.K. had always been a magical place.

It was where The Famous Five had all these magical adventures, and where my own Dad, a civil servant, and my Mum, a bilingual secretary, had the romance which had resulted in me, their “love child.” My mum had told me many thrilling stories of the many years she spent in the U.K.—being educated in a fancy 6th form college, as an adult going to the Ritz for tea, and later meeting my Dad in Geneva, and reconnecting with him when he came to Oxford to study.

My experience in London was very different. Unlike my mum, I wasn’t the child of a wealthy man, and so I studied part time, and worked to pay my fees as a home student. I worked as a receptionist for the local branch of a popular chain of pizza restaurants, where I had to get used to customers screaming at me when I asked them to do things like spell out their address because I didn’t understand their accent. I buried myself in my books, including bell hooks’ Ain’t I a Woman: Black women and feminism. It was one of the assigned texts on my university reading list, and it was my introduction to feminism.

Reading that book not only changed my life, it made me the feminist that I am today. hooks helped me understand not only how racism functioned in society historically and in contemporary times, but placed sexism—a system I was made intimately aware of growing up as a girl in Ghana—on an equal footing with racism—a system which, until then, I had been sheltered from as a privileged middle class girl in a Black majority country.

hook’s analysis of sexism, and the ways in which the institutions of slavery and white supremacy reinforced gender norms were like nothing I had read before. In her first sentence of this now classic text she stated: “In a retrospective examination of the black female slave experience, sexism looms as large as racism as an oppressive force in the lives of black women.”

People like her never die, they live on—wherever they may be in the cosmos—and through their incredible body of work continue to inspire women like me to show up as ourselves.

I had never heard anyone articulate anything so boldly and directly. That even within slavery—the most oppressive and dehumanizing system—black women suffered particularly because of their gender. hooks went on to show how after manumission, black women organized around issues of gender. How black women were active in the suffragette movement but were discriminated against, and marginalized by racist white women who, even at their most liberal, saw the issues that black women experienced as related to their race and not their gender. In a chapter titled “Black Women and Feminism” hooks writes: “The 19th-century women’s rights movement could have provided a forum for black women to address their grievances, but white female racism barred them from full participation in the movement.”

I think of these words often. I have been active in African and global feminist movement spaces for about fifteen years now, and I think it’s important for feminists to always ask ourselves these questions. Who is being barred from fully participating in the movement? Are our movements creating space to amplify the concerns of the most marginalized women? Whose voices need to be magnified? A radical feminist politic demands that we do this—that we center the needs and leadership of historically oppressed women—women with disabilities, sex workers and trans women to name just a few.

In this current season of my life, while stepping more fully into my life as a writer, the bell hooks book that resonates most with me is Wounds of Passion: A Writing Life. It is a book that affirms the value of writing about sex, relationships and deeply personal intimacies. I have been re-reading this book slowly, as an indulgence. Sometimes I lie in my hammock and read a few pages, other times I take it to bed, and read a bit more before falling asleep.

In her preface to this memoir, hooks writes: “This book of ruminations on the early years of my writing life draws together the concerns that women (of all races and classes) dreaming of becoming writers faced as a consequence of movements for sexual liberation and feminist struggle. The pressing issues of whether women could have love and write, whether we could be sexual adventurers and use those experiences as imaginative groundwork…” (bold and italics mine)

Years before I first read Wounds of Passion, I had made the decision to become a sexual adventurer. I decided to do so publicly and proudly, by documenting my sexual adventures and misadventures on my blog, “The Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women.” I did this as a way to challenge myself; to break away from the “good girl” norms that had been instilled in me as a child.

Growing up in Ghana I had been made to understand that having sex with multiple people somehow tarnished you as a person, and as a result I married the first man I had been intimate with. In my late twenties I broke away from that limiting belief and decided deliberately to embark on a journey to discover my sexuality. That led me to a celebration of what I now recognize to be true—that sex is political, and women have an inherent right to pleasure, and ownership over our own bodies.

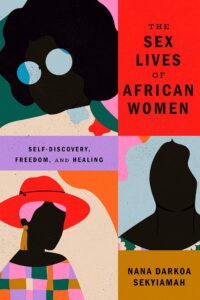

In writing my blog, I soon became aware that work around sexual rights was only political when it was about the collective, and so I started to encourage other African women to also share their stories around sex and sexualities. Eventually, this online dialogue with women from the continent and from the diaspora gave me the idea for a book of my own—The Sex Lives of African Women, in which I highlight some of the conversations that were most meaningful for my own journey. So it was exciting for me to discover later that hooks thought our sexual experiences and practices could be the foundation for imagining new liberatory possibilities. It felt like an affirmation and an endorsement of the work I do and the book I wrote.

hooks writes, “All that I had learned about love between men and women growing up only made it clear to me that this kind of loving was not for me. I saw so much jealousy—the kind that hurt—the shoot and cut kind—the if I can’t have you nobody can kind.” (italics in original) This kind of possessive, all-consuming love that has been romanticized in heteronormative relationships is one that I have learned to avoid. Like hooks, I do not want “…to be owned, possessed, fought over.”

The women whom I personally found most inspiring, and who are cited in the Freedom section of my book, were women like Fatou, a Senegalese woman in her 60s who had navigated polyamory and living life on her own terms while living in a conservative Muslim majority society.

Like many people around the world, I was deeply shaken when we lost bell hooks at the end of 2021. I had to remind myself that people like her never die, they live on—wherever they may be in the cosmos—and through their incredible body of work continue to inspire women like me to show up as ourselves—as feminists, mothers, lovers, daughters, and yes, as women who create using their very lives as blueprints to imagine feminist futures.

For me, this has meant living and sharing my truths openly. It has meant allowing myself to be vulnerable by sharing deeply personal experiences of child sexual abuse for instance, something that hooks herself did not shy away from. It’s also meant boldly claiming my voice to speak up and out in community with other African and Black feminists. It’s meant a recognition of the politics of pleasure, and a commitment to creating and co-creating a world where the least amongst us thrives so that we may all bloom.

_____________________________________________________

Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah’s The Sex Lives of African Women is available now via Astra House.

Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah

Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah is a feminist activist, writer and blogger. She is the co-founder of Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women, an award-winning blog that focuses on African women, sex and sexualities, and she writes frequently for The Guardian, Open Democracy, and elsewhere. The Sex Lives of African Women is her first book. She works with the Association for Women's Rights in Development (AWID) as director of communications and tactics. She lives in Accra, Ghana.