The Yinzers of Glasgow: On the Scottish Origins of Pittsburgh’s Unique Dialect

Ed Simon Demystifies and Reclaims Pittsburghese

The city center of Glasgow, Scotland—that iron-and-glass-forged, cobblestoned fortress of a hilly, rainy, foggy metropolis—is bisected by the dueling high streets of Buchanan and Sauchiehall. There are any number of landmarks to draw your attention if ambling down either of these bustling thoroughfares as the last squibs of Caledonian light fight their losing battle of attrition during a brisk November afternoon.

For six months in 2006, Glasgow was my home across the Atlantic, and I often spent those glum Scottish afternoons in precisely this sort of aimless wandering, past the Victorian magnificence of the exposed-girder Queen Street rail station and the imposing, imperial grandeur of St. George’s Square; the smooth, modernist sandstone edifice of the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall with its green-patina statue of the slightly depressed-looking Scottish first minister Donald Dewar and the Palladian, neoclassical granite of the Gallery of Modern Art with its equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington in front, inevitably vandalized again each night in the exact same way, with some waggish Glaswegian placing an orange traffic cone upon that esteemed head.

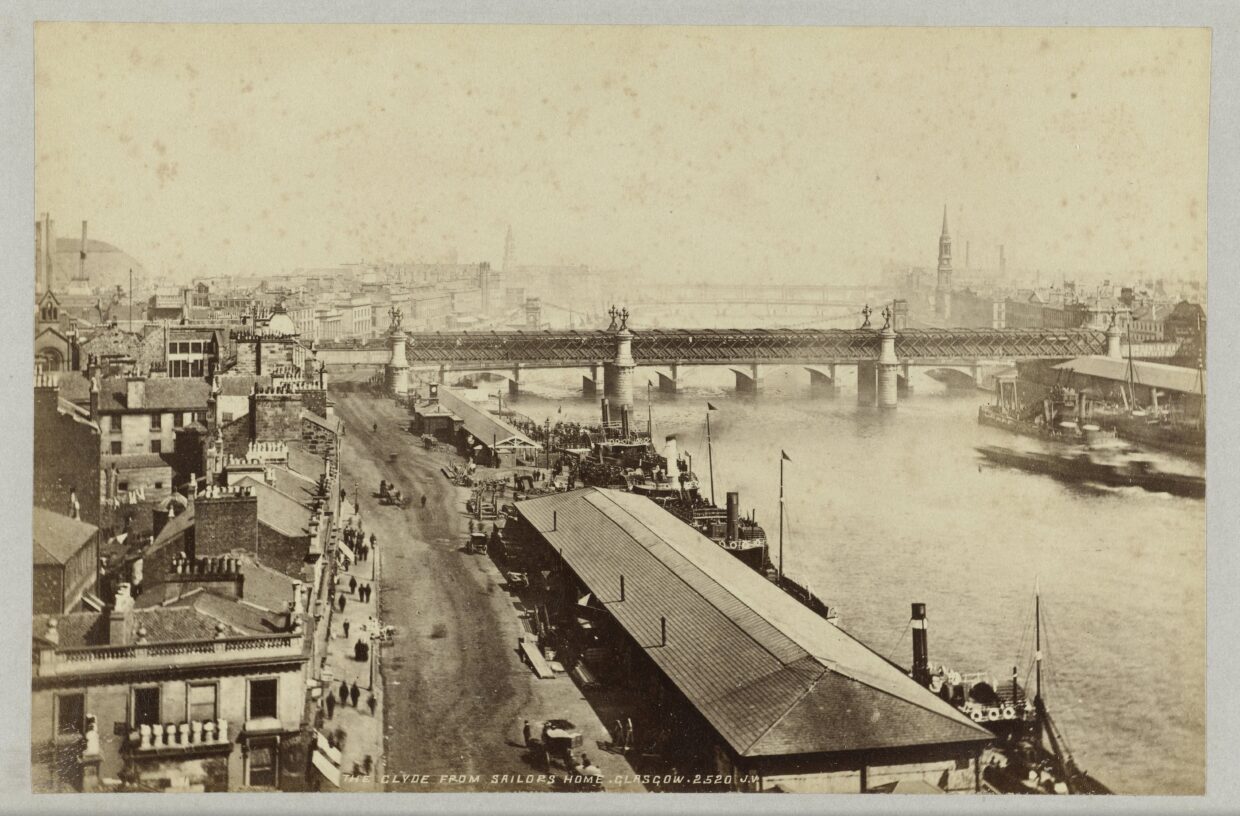

Glasgow, that city of some six hundred thousand people on the River Clyde, once Great Britain’s veritable second city, despite its reputation for filth and grime grew rich in the nineteenth century on coal mining and iron forging, textiles and food canning and most of all shipbuilding but saw a precipitous decline in both esteem and population with the disastrous neoliberal economic reforms of a generation ago.

As a Pittsburgher, this was a narrative I already knew. Because it has always been a place strung between capital and labor, the wealthy and the workers, Glasgow long ago developed a widespread, irreverent radicalism, as evidenced by the conical crown atop the fussy English Duke of Wellington—a perspective about injustice and absurdity that wasn’t unfamiliar to me either.

Listening to punk at that incomparable dive King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut or enjoying an Irish ceilidh at Failte Pub, pounding a pint of Guinness at Waxy O’Connor’s or Tennant’s at the Old Toll, getting a curry from Karahi Palace or a late-night doner at the appropriately named Best Kebab, grabbing an Irn-Bru to cure a hangover at Boots the Chemist or devouring a Cornish pasty purchased from Greg’s—it all felt strangely similar even if so obviously different, as if looking at your own reflection through a slightly opaque bubble-glass window at any one of the pubs lining Buchanan and Sauchiehall.

There is more than a spiritual congruence between Glasgow and Pittsburgh, as Kelman’s “yins” would indicate, the s that ends that word so perilously close a sibilant to the z in yinz and the words so nearly used identically.

Glasgow, I thought, is kind of like Pittsburgh. And then, walking through Glasgow again, I hear it: “There was a couple other of yins as well.” What?

First, a confession—I never heard that exact sentence, though I heard many similar ones with that particular second-person plural in evidence. This example is from the Scottish author James Kelman’s 1994 controversial stream-of-consciousness, Booker Prize-winning, working-class classic “grit lit” novel How Late It Was, How Late, penned in often indecipherable phonetic Glaswegian. Incidentally, variations on the word yin or yins appear sixty-seven times in Kelman’s novel, a tough, bruising, obscene and profane account of a shoplifting, alcoholic ex-con navigating the absurdities of Scotland’s largest city.

Despite the anger from many among the English literati at this first Scottish book to win a Booker, How Late It Was, How Late is written in the sort of dialect that can only really be heard by people from “Used to Be Important” places, from the cauldrons of industry and the forges of labor, from the cities that built the world but were then abandoned when factories closed and mills shuttered, only to have to reinvent themselves over and over. “Folk take a battering but, they do; they get born and they get brought up and they get fuckt,” writes Kelman. “That’s the story; the cot to the fucking funeral pyre.”

There is more than a spiritual congruence between Glasgow and Pittsburgh, as Kelman’s “yins” would indicate, the s that ends that word so perilously close a sibilant to the z in yinz and the words so nearly used identically. For those unfamiliar with yinz—though I imagine if you’re currently reading this book, you most likely know what it means, albeit it’s becoming increasingly rare in usage—it’s simply the Western Pennsylvania second-person plural, the Pittsburgh equivalent of y’all down South or youse in Jersey and New York.

It is, admittedly to many outside the region (and to some within it), a strange-sounding word. Where there is a certain sense in how you and all can be smoosh-mouthed over time into that aouthern all-purpose word, yinz has a slightly alien quality about it, a combination of sounds that don’t quite make sense, a shibboleth of identity to those who live in Pittsburgh and, apparently, Glasgow. Because Kelman’s “yins” and the “yinz” you hear at Ritter’s Diner in Bloomfield, Gough’s Tavern in Greenfield, Gene’s Place in South Oakland or the Squirrel Hill Café literally have the same origin.

As any good Glaswegian would tell you, yin simply means “one,” but though obscure, it’s actually the same with Pittsburgh’s most distinctive linguistic attribute. Just as “y’all” is a compression of two other words, so does “yinz” come from you ones. That phrase is a direct translation of the Gallic Scots, where the second-person plural is perfectly grammatically correct.

Calling it the “most salient morphosyntactic feature of local speech,” Carnegie Mellon University rhetoric professor Barbara Johnson explains in her study Speaking Pittsburghese: The Story of a Dialect (published as part of the prestigious Oxford Studies in Sociolinguistics series) that “‘yinz’ was brought to America by Scotch-Irish immigrants… the descendants of Protestant people from Scotland and northern England.” From the shores of the Clyde then to the Monongahela, Allegheny and Ohio, it seems that my ears on Sauchiehall and Buchanan weren’t in error.

Because I’ve occasionally fooled myself into pretending that education can easily obscure markers of regional identity and class, I never hear my own Pittsburgh accent when I’m actually in the city, and by no means would mine sound particularly thick to any born Yinzer. Yet when I’m somewhere else, particularly in the Acela Corridor of the Northeast, I apparently sound like I’m sitting on a frayed red canvas stool at Chandos in Homestead drinking an Iron City (note that the first word is pronounced exactly like the prefix in Irn-Bru, the Scottish pop I mentioned earlier).

I’ve never uttered “yinz” in any way other than ironically, but if vocabulary can be a choice, pronunciation is destiny. To wit, words like cot and caught sound identical when I speak them—a characteristic of Pittsburgh English; when tired, I pronounce the “vowel in words that rhyme without as a monophthong rather than a diphthong” as Johnson writes, which is to say that down becomes “dahn,” town becomes “tahn,” field becomes “filled,” steel becomes “still,” and so on. Other markers are sprinkled in as well; I’ve got the tendency to convert declarative sentences into what sounds like an interrogative, and dropping the words to be from a sentence (as in “The car needs washed”) sounds completely grammatically correct to me, even though I have a PhD in English.

Finally, there is the telltale vocabulary, the more conscious aspects of dialect that in Pittsburgh can include everything from calling a vacuum cleaner a sweeper to saying that a nosy person is being nebby, telling people that a room that needs to be cleaned has to be red-up or describing a disagreeable person as a jagoff. The latter is supposedly from the burr-like thorns of the English and Scottish Midlands jagger-bush, but everybody in Pittsburgh knows that the insult is just as obscene as it sounds and references exactly what you think it does, even if until 2016 it could still be published sans censor marks in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. This is the lexicography of a thousand black-and-gold novelty T-shirts sold from sidewalk stalls on Saturdays in the Strip District or proudly worn at a Steelers tailgate.

“To outsiders, the Pittsburgh dialect may sound odd,” notes Andy Masich, director of the Senator John Heinz III Regional History Museum in his foreword to Pittsburghese: From Ahrn to Yinz. “Even Pittsburghers argue whether jagoff can be uttered in polite society.”

Because there are few famous examples of a Pittsburgh dialect—Michael Keaton speaks with a wonderful accent, especially as the character Beetlejuice, and outsider Nick Kroll does a fairly good imitation in the skit “Pawnsylvania” from his national sketch comedy show—it tends to confuse people. When entering a hardware store in the small Massachusetts town that I lived in for two years, there was simply incredulity and incomprehension at how I was speaking (though perhaps that was just Boston friendliness). They had none of the r’s, and I had all of them. They thought that I was a pirate.

Pittsburghese, Western Pennsylvania English or, technically, the North American North Midland dialect—however you choose to identify the accent, what’s unassailable is that such a way of speaking is strongly identified with the archetypal figure of the Yinzer.

As an accent, Pittsburgh English may be centered in the city, but today it’s more likely to be heard in the outer counties of Western Pennsylvania. Linguistically it’s clearly a variation on northern Appalachian English; yinz or some permutation is frequently heard in western Maryland, eastern Ohio and the West Virginia panhandle. Within Pittsburgh, the accent has a curious aspect to it: that vaguely twangy Appalachian pronunciation with all those loan words from Polish, Neapolitan and Yiddish, making the dialect sound a bit like if somebody from Brooklyn was doing a really poor imitation of somebody from Kentucky, an urban Deadwood kind of talk.

Pittsburghese, Western Pennsylvania English or, technically, the North American North Midland dialect—however you choose to identify the accent, what’s unassailable is that such a way of speaking is strongly identified with the archetypal figure of the Yinzer. As a Townie or a Southie is to Boston, so is the Yinzer to Pittsburgh. Inextricably bound with issues of class and race, a Yinzer embodies the stereotypes associated with White blue-collar Pittsburghers. If someone’s voice evidences that “vowel in words that rhyme without as a monophthong rather than a diphthong” as Johnson put it, then certain assumptions are made.

In popular culture, rightly or wrongly, a Yinzer is understood as somebody for whom nostalgia is a birthright (often focused around 1974, when the Steelers first won the Super Bowl). Their wardrobe consists of only black and gold; the needle on their car’s radio never wavers from 96.9, the home for classic rock; and the men sport goatees or beards, maybe a mullet (true for the women as well). If responsible for shoveling the filthy, black, exhaust-stained snow to make a parking spot on a narrow cobblestoned street in front of their rowhouse in the depths of February, a Yinzer will most definitely mark their territory with a flimsy folding chair that best not be moved by an interloper. A Yinzer subsists on a diet of kielbasa and pierogis, salads and sandwiches heaped high with French fries and draft after draft of Iron City Beer (maybe Rolling Rock).

In the stereotype, and perhaps the reality, Yinzers manifest a strange fusion of friendliness and toughness, an erratic personality that can seemingly swing between Brooklyn crankiness and Peoria pleasant, an extroverted, gregarious people whose conversation can sound like screaming. Yinzers are kitsch made manifest. More than anything, in a metropolitan area that finally sees its population growing again after decades of decline, a Yinzer is somebody whose roots have been here for generations.

Like any broad portrait, there are things recognizable in such descriptions and there are things that are cartoonish. Certainly, a generation or two ago—when the word yinz was heard far more frequently—the self-designation Yinzer would have been anathema. Now, however, there is an entire cottage industry of Yinzerhood, from the (excellent) T-shirts at Commonwealth Print Shop to the Yinz Coffee chain. Stereotypes about Pittsburgh are celebrated on hats, beer koozies, coasters, mugs, scarves, jackets and a truly horrifying doll called the Debbie Yappin’ Yinzer Talking Plush.

Despite the preponderance of genuine Pittsburgh accents, from the much-missed and now departed Steelers radio broadcaster Myron “Yoi and Double Yoi” Cope to the beloved 1980s rock musician Donnie “Dahnnie” Iris, the current most famous Yinzer is Greensburg native Curt Wootton of the contemporary web series Pittsburgh Dad.

Premiering in 2011 and quickly gaining viral popularity throughout the metropolitan region, Pittsburgh Dad is a sort of meta-comedy deconstruction of the sitcom, featuring only Wootton facing the camera, often in a stereotypical “Pittsburgh Room” (a sort of faux wood–lined basement man cave filled with sports paraphernalia) speaking in an exaggerated accent and namechecking any number of references from Eat ’n Park to Giant Eagle to Kennywood, with his monologue punctuated by an almost mocking laugh track.

Wearing a pair of what can only be described as fantastically unhip glasses and a polo shirt with the IBEW Local logo, Pittsburgh Dad is often drunk, frequently screaming at his children, a superstitious if poorly catechized Catholic and disturbingly obsessed with the Steelers and Penguins. Total views of Pittsburgh Dad’s videos are at an astounding seventy-seven million. Like a lot of Yinzer humor, there is a spirit of affection when the Pittsburgh Dad videos are shared among locals.

With Yinzer jokes more generally, however, there is the threat that loving caricature can veer into some sort of working-class minstrel show, not to mention when Yinzerhood becomes a means of separating out “Real Pittsburghers,” a way of excluding recent transplants or minorities whose roots in the region can go back just as far as those of anyone with the accent (there is, notably, a seeming contradiction in the idea of there being Black Yinzers).

That’s not to say that Pittsburgh Dad isn’t funny—it often is, though I imagine the humor doesn’t translate well to those who aren’t already in on the jokes. More importantly, it’s not to say that Pittsburgh Dad doesn’t have a bit of subversive bite to it as well—it does. A particularly funny episode contrasts Pittsburgh’s burgeoning reputation as a weird hipster Mecca in the mold of Portland with the folksy provincialism of the past when Wootton accidentally takes his children to Anthrocon, the annual convention of the plush animal-dressed fetishists known as furries, having perilously and accidentally assumed that it was a gathering of sports mascots.

Pittsburgh Dad deftly interlaces the warm and the cynical with an almost Glaswegian proficiency, as when Wootton recounts the mythic tale of the suburban Century III Mall’s genesis, claiming that the

steel mills would transport their toxic waste by train to a little slice of heaven in West Mifflin called Brown’s Dump.…Then they’d slowly spill out that glowing, molten toxic waste onto the hillside, into the environment, and it was no big deal….In a few months, up sprouted the best one million square foot of commerce the Western world had ever seen!

Delivered in the accent or not—maybe especially because it is—the monologue has a bit more fang than might first be assumed. Pittsburgh Dad isn’t exactly How Late It Was, How Late, but it’s not entirely perpendicular to it either.

There’s a reason for the popularity of Pittsburgh Dad, as well as, more broadly, the niche of Yinzer branding. Australian urban theorist Laura Crommelin writes in the journal Place Branding and Public Diplomacy that such representations of “yinzer culture…function as both DIY urban branding and as a reflection of local reactions to Pittsburgh’s economic, social and brand transition.” Of all the major metropolitan regions to be cratered out by the neoliberal industrial collapse of the late 1980s—Cleveland, Detroit, Flint—Pittsburgh has by far had the most successful resurgence, bolstered by the tremendous Gilded Age wealth that still powered deep-pocketed nonprofit foundations within the city, as well as the transition to a medicaland technology-based economy.

In such a context, the proud embrace of Yinzerdom is a type of resistance against new economic forces that threaten to transform the region, the same sorts of economic forces that every native Pittsburgher knows once demolished it. Yinz has moved from the realm of actual conversation and into the hipster domain of ironic reclamation, of screen printed T-shirts with Pittsburgh lingo on them or handmade cross-stitches that say things like “Red Up Dis Room,” “J’eet Yet?, n’at,” though as Johnson said in an interview with the Pittsburgh City Paper’s Chris Potter, “People can do this lovingly, and I think a lot of the hipster stuff is kind of loving.”

Like any nostalgia kick, there are dangers to such representations, though. Yinzer discourse can solidify a genuine division, especially between those of us who have been here forever and those just now discovering the beauty of Pittsburgh. It can confirm the suspicions about the city being backward, provincial and insular.

Even more insidiously, there is a way in which it bolsters some truly noxious understandings of who belongs and who doesn’t. You’ll note that while a Yinzer can be many things—Scots-Irish and CarpathoRusyn, Czech and Slovak, Greek and Italian, Polish and Ukrainian, German and Irish Catholic—hardly ever is the Yinzer envisioned as Black (or Asian, or Hispanic). As Damon Young accurately half-jokes in his book What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker: A Memoir in Essays, “Pittsburgh itself is so segregated that any place within a ten-mile radius of the city with more than seven black people there at one time feels like the Essence Festival.”

Then there are the complexities surrounding the self-designation of the term Yinzer: the way in which, despite how affectionately such portrayals may be intended, there is still something a bit insulting about the whole thing.

When I was speaking about my previous book on the city, An Alternative History of Pittsburgh, I was at a loss following one audience member’s question about what my intent had been in writing the title. Fumbling through various inchoate justifications for why I’d written it, explaining how my goal had been to express an aspect of the city that was complicated, nuanced, sophisticated and not always adoringly positive, I may have said that I wanted to “avoid writing a particular type of book.” The woman who’d asked the question clarified my meaning: “A Yinzer book?”

That was exactly it—I didn’t want to write a Yinzer book. I wanted to give a sense of my love for Pittsburgh while avoiding halcyon and corny expressions of mindless civic boosterism; it was my intent to try and express a bit of the grit and determination of the city, but I was loathe to have anything too Yinzer-y about the whole thing (that particular second-person plural appears only once in the entire book).

Why the chagrin? Why my own Pittsburgh cringe? “Sometimes we’re so afraid of what others think, we’re afraid to declare who we are,” writes former Pittsburgh Post-Gazette columnist Brian O’Neill in his seminal collection The Paris of Appalachia: Pittsburgh in the Twenty-First Century. “It’s not East Coast. It’s just Pittsburgh, and there’s no place like it. That’s both its blessing and its curse.”

O’Neill’s book went a long way toward popularizing that particular nickname, which I’ve also always been ambivalent about. From a geographic perspective, the placement of Pittsburgh in that mythologized mountain range is unassailable. Allegheny County is unequivocally the most populous in the entirety of the Appalachians.

When Kelman won the Booker Prize in 1994, the British press was outraged that a book written in what was such a supposedly low dialect was given those laurels, offended that the author had the audacity to hear anything beautiful in Glaswegian.

Yet the connotations of “Appalachian” are what they are, so that I—along with many people in the region—have historically avoided it. A bit like the accent, there’s a sense in which the associations reflect something derogatory about how others see us rather than a reality that we know to be true. And yet, despite its complexities, despite what’s admittedly problematic about it, why avoid speaking in the dialect, why obscure the Pittsburgh in our own voice?

The accent hasn’t endeared us to many. In 2014, Pittsburgh beat out my wife’s native Rhode Island in a Gawker magazine sweet sixteen–style competition to find the nation’s ugliest accent, much to the delight of local news media, for the city’s honor would have been besmirched had it been decided that ours was only the second-worst accent in the United States.

To be sure, there is a cankered kind of pride at such national scorn, an estimably admirable combination of confidence and humility that knows precisely what such rejections and mockery are worth. There is something also kind of incredible in the circuitous route by which yinz became so intrinsic to the Pittsburgh identity, this linguistic coelacanth hidden on the hills and in the valleys of Western Pennsylvania.

From Ulster and Derry, Birmingham and Manchester, Edinburgh and Scotland, yinz was carried into the frontiers of Western Pennsylvania, now spoken by those who’ve never seen Midlothian or the Clyde—now it is rather the grandchildren of Krakow and Warsaw, Hamburg and Frankfurt, Dublin and Kerry, Prague and Budapest, Charleston and Richmond, Naples and Pescara who speak this venerable Scottish word. Few of us are directly descended from the Caledonian hills anymore, but like any example of glorious hybridized culture, we took some of that language and mixed it with a million different things.

It’s true that there can be a sense in which the barrier to entry is high in Pittsburgh, but I’ve often joked that membership can be more affordable than you might expect, for if you like us and you’re willing to wear black and gold, you’re given a ticket. There was an exceedingly friendly gentleman whom I knew from the Pacific Northwest who moved here and full-throatedly embraced the poetic necessity of the word yinz, that great gender-neutral pronoun.

Despite not being the fourth generation to live in his family’s house in Greenfield or Brookline, there was something of the spiritual Yinzer about him. All of which reminds me of a strange and beautiful column published in 1914 by James G. Connell Jr., an executive at the West Penn Paper Company of all things, that was titled “The Pittsburgh Creed.” Connell wrote,

I believe in Pittsburgh the powerful—the progressive….I believe in Pittsburgh of the present, and her people—possessing the virtue of all nations—fused through the melting pot to a greater potency for good.…I believe that those who know Pittsburgh love her, “her rocks and rills, and templed hills.” I believe that Pittsburgh’s mighty forces are reproduced in a mighty people, stanch like the hills,—true like steel.

Nothing is backward, provincial or insular about that. And I think of all of us, this diversity of peoples, maybe first from Scotland and England but joined by immigrants from Germany and Ireland, Italy and Poland, Black Americans coming north from Dixie and Jews fleeing eastern European pogroms and now arrivals from China and India, Ethiopia and Nepal, and the glorious strangeness and beauty and absurdity that we can all make this culture of Pittsburgh our own, and change it a bit, and make it better. What shame is there in being a Yinzer, whence the “Pittsburgh Creed” was derived?

When Kelman won the Booker Prize in 1994, the British press was outraged that a book written in what was such a supposedly low dialect was given those laurels, offended that the author had the audacity to hear anything beautiful in Glaswegian. He answered such objections in his acceptance speech, saying, “[My] culture and my language have the right to exist, and no one has the authority to dismiss that.” What do yinz think of that?

______________________________

The Soul of Pittsburgh: Essays on Life, Community, and History by Ed Simon is available via Arcadia Publishing.

Ed Simon

Ed Simon is the Public Humanities Special Faculty in the English Department of Carnegie Mellon University, a staff writer for Lit Hub, and the editor of Belt Magazine. His most recent book is Devil's Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain, the first comprehensive, popular account of that subject.