Raimundo

“Raimundo Gaudêncio de Freitas,” in a tentative stroke, barely touching the paper. He tamed that damn pencil and wrote, for the first time, his full name. Seventy-one years old and he starts getting ideas, as he likes to say, about learning to read and write as an old man. Raimundo came easy. But Gaudêncio was complicated, dense with longing, with its five vowels and an accent. Freitas was made of blood.

Not for lack of wanting, ever since he was a boy. But his father said writing was for people who don’t need to put food on the table. Raimundo went to work young. At night, his arm, tuned to the rhythm of the scythe, needed rest, there was more the next day. His desire to learn slowly gave way to need. His future was written out in front of him, a gift from his father, a family man who owned a bit of land, who signed with a thumbprint when his word wasn’t enough. What couldn’t be said, was kept silent, a thought. Raimundo never became a family man or owned any land. He pulled up his roots, carrying the letter in his shirt pocket.

A whole letter. One word after another, how many of them? Sending a letter to someone who can’t read, imagine that. The tip of the pencil hovered over the line. The next name was the one of the person who’d written the letter, fifty-two years ago. Next to the notebook, the hardened envelope, still sealed. Raimundo never let anyone read it and grew old wishing to know what it said, the desire growing with him. An elderly fetus, late blooming. A lifetime kept in that letter.

Cícero

Next to his own, he wrote Cícero’s name. Did it end with a u? It looked nicer with an o. Only six letters, but it could hold so much, it was heavy. Like the cross, which started with a c, like caring and cock.

They’d known each other since they were kids, born in the same community. When they were seventeen, at a forró dance at the square, Cícero’s eyes, the color of the earth, plowed right through Raimundo.

“Nice party, huh, Gaudêncio? A lot of pretty girls.” “Yeah.”

Raimundo thought Cícero was handsome, with a beauty similar to the one he saw in the girls. Beating heart, blood rushing to the pit of his stomach. Stalk planted.

Lying in the hammock, wild images in his mind tossed and turned his body. A man’s body, both his and Cícero’s. Man with woman, because man with man wasn’t right, that’s what everyone said, a man needs to think women look good, a man who thinks other men look good isn’t a real man. But he was a man, and he thought Cícero was handsome! And did Cícero think he was handsome too? He’d come to talk about girls and dance with them. With their hair fragrant with coconut oil, soft breasts, plump thighs. Cícero eagerly held the pretty girls rubbing against his leg, straddling.

A few days later, the two of them were out alone, working the land that belonged to Cícero’s father. A quick light drizzle moistened the ground. Raimundo’s gaze slipped over to Cícero’s body, his bare chest hard, covered in sweat and dust. Landscape that would stir a desire to fly in any caged bird. Caged Raimundo. When Cícero noticed, Raimundo looked away, but the gleam of the scythe soon cut through his patience, and again he ventured another glance at his friend, hoping his mind would decide whether it wanted what his body wanted.

“What is it, Gaudêncio?”

And now what? he’s going to pick a fight with me, tell the whole town, Raimundo is a fag, What’s with all the staring? why did you have to go and do that, Raimundo? but he’s my friend, he won’t say anything, it didn’t mean anything anyway, nothing, really.

He wanted to answer. He didn’t answer, but in a way he did. Cícero slowly moved closer, then even closer, his face only a few inches from Raimundo’s. With one hand, he grabbed the nape of his neck, from the left, taking hold of the lock of white hair there, while he clasped his waist with the other. Raimundo didn’t move. He buried himself in those brown eyes, feeling the warmth firing up his body and dilating his veins, not knowing where to put his head, his hands, his feet, or his member, growing between his thighs. Dirt saliva tongues arms legs mouths hunger life.

They met almost every day. It was risky. Always in the bushes. In the bushes they hid from everyone else while they revealed themselves to each other. Man and man, they got along very well, they liked each other. A good taste, but that left something sour in the back of their minds.

It lasted two years.

“What the fuck is going on?”

Cícero’s father caught his son on all fours, clenched his right hand into a fist, and knocked him to the ground with a punch.

Seu Nonato, he’s your son, we’re friends, I grew up going to your house and Cícero coming to mine, we started to like each other a little while ago, we aren’t hurting anybody, you didn’t have to hit him like that, Seu Nonato, please don’t hurt him, he’s your son, get up, Cícero, get up.

In the end, Raimundo didn’t say any of this, while Cícero wiped the blood from his lip with the back of his hand.

Seu Nonato yanked his son by the arm.

“Get up, Cícero, get up, put on your clothes and go home.”

Raimundo looked like he was going to help, but then stopped. Seu Nonato’s face was red, twisted in a grimace.

“And what about you, huh? You just wait until I tell your father. He’s going to beat you to a pulp.”

Cícero looked back one more time.

We shouldn’t have been here, out in the open, The shade from the cashew tree is nice, Gaudêncio, but today I want to be in the sun, we took too many chances, that’s what happened, staying out here by the river, but at the time, at the time we knew it couldn’t be any other time, all those days without seeing each other, touching each other, when one body leaned into the other, it was all the yearning from those ten days, talking, it was the yearning from much longer than that, a whole lifetime of desire in there, all that had passed and that was yet to come, every time we felt that sweet agony inside, saying yes to desire and desire clutching the yes from our bodies, from our heads, from time, and I couldn’t wait any longer, and neither could he, we just couldn’t, and that was why I came, Cícero, you feel that way too, but you kept going on about having a future, having a wife, a child, you got scared, it scared me too, I had a horrible feeling here inside me, being away from you, I couldn’t take it anymore, I couldn’t have just let your fears decide our future, your words that last time we were out by the cashew tree, and then you left, I came after you and then what, what’ll happen now? your family will find out, my family will find out, if this is already confusing to us, imagine to our fathers, the heartbreak, the anger they’ll feel, you know what they think of people like that, like the two of us, don’t you? they think the worst, that it’s worse even than disease, where are my pants? I’ll have to talk to my father, and say what? and to my mother? there are no words, I got to find the few I got and tell them, they’ll find out anyway, what else is there to hide? what if we can’t be together anymore? it’s going to be a fight, and not just with our own heads, but with other people’s too, you know? we’ll fight if we have to because nothing can keep us apart anymore, they’ll have to literally cut us off, our flesh, to tear us off piece by piece.

Raimundo finished getting dressed. The sun was starting to drop from the middle of the day. Before leaving the riverbank, he looked at the cross that marked the river and that would mark his life. He headed on home.

__________________________________

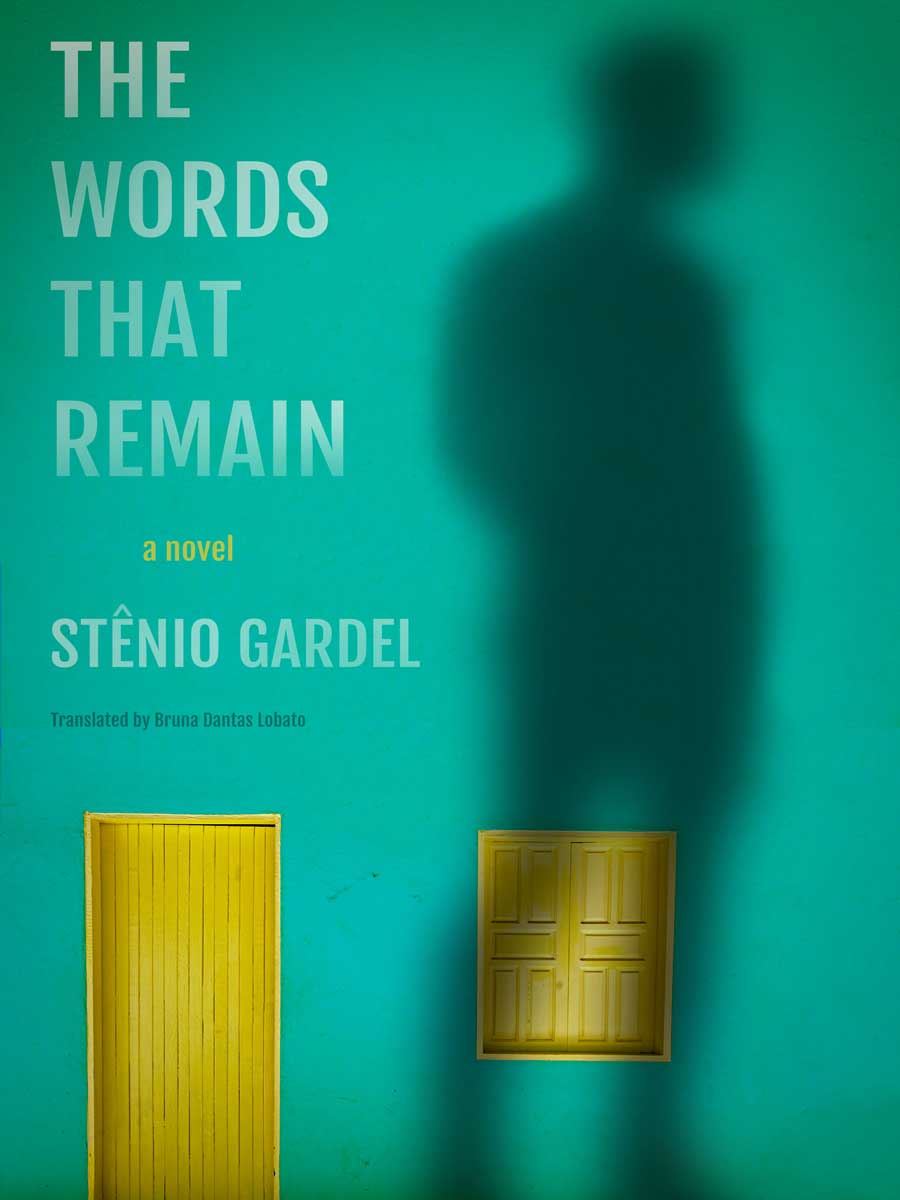

Excerpted from The Words That Remain by Stênio Gardel (translated by Bruna Dantas Lobato). Used with permission of the publisher, New Vessel Press. Copyright © Stênio Gardel/ Bruna Dantas Lobato.