The Woman Who Brought Dostoevsky and Chekhov to English Readers

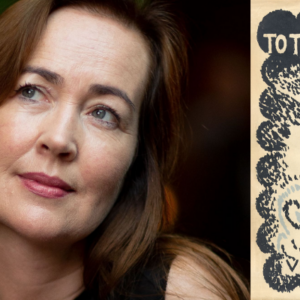

Sara Wheeler on Constance Garnett and the Problem

of Era-Specific Translations

My first publication was a translation, not something I wrote myself. It was an essay in Greek about the poet C.P. Cavafy for a literary anthology of that kind of thing. Before taking up Modern Greek I had spent thousands of hours of my youth translating Homer for my studies—probably too many hours, when I should have been doing something else. I am not very good at written translation, and have a tremendous respect for those who carry it off. Having a smaller vocabulary than English, Russian in particular requires the translator to wrestle constantly with nuance. (Dusha, for example, means “soul,” and also “heart” in a figurative sense. The word appears more than a hundred times in War and Peace.)

The one I hold dear to my own dusha, as a woman, and as a translator, is Constance Garnett. Born in Brighton in 1861, Garnett translated 70 volumes from Russian, including all Dostoyevsky’s baggy monsters. She was an indefatigable worker who moved through the literary and political circles of a troubled time and emerged as a heroine, always on the side of the poor and oppressed, fighting in a man’s world. She was the opposite of a Little Englander, determined to see things from an international point of view.

Fair-haired, short-sighted, and in poor health all her life, Garnett had a pinched childhood. When she went up to Newnham College, Cambridge, as a scholar at 17, she had never before left Sussex. She read classics and math, both of which provided rigorous training in the art of translation and the expression of precise meanings. She began learning Russian just before she turned 30 when she fell in with a gang of fiery exiles. She lectured a little, taught, moved to London, and associated with the Fabians—a movement which she later joined, and later still left. She was friends with George Bernard Shaw, who claimed he would have liked to marry her had he been richer.

Garnett worked at the People’s Palace, a library designed to improve the education of working people in London’s East End. She married Edward Garnett, a publisher’s reader and would-be novelist who started a newspaper for cats (motto “Cave Canem”) which included a food column. His family had always been sympathetic to political refugees, and the newlyweds embarked on married life with an altruistic sense of purpose. For her part Connie befriended many Russian Jews who had fled persecution after the assassination of Alexander II. The couple set up home in Surrey in a cottage where Constance once picked 27 quarts of blackberries in a day and found a mouse preserved in a jar of treacle.

In 1905 the Garnetts took a flat in Hampstead. Edward’s father lived nearby in Tanza Road, and to get there Constance had to walk past the butcher’s shop which is now my house—perhaps she bought lamb chops in the very room where I am writing these pages.

She began translating from the Russian with Turgenev, with whom she felt a deep affinity. Her work rate was astonishing. Her friend D. H. Lawrence described her sitting in the garden accumulating a tottering pillar of sheets on the grass alongside her. Of her Turgenev, Joseph Conrad, another friend, wrote, “She is in that work what a great musician is to a great composer—with something more, something greater. It is as if the interpreter had looked into the very mind of the Master and had a share in his inspiration.” Her husband meanwhile became one of the most distinguished editors of his generation, nurturing the careers of such giants as Conrad, and as a result he wielded influence. He too was committed to Russian literature, and championed Russian writers all his life, once declaring, “The Russians have widened the scope and aim of the novel.”

Garnett made Dostoyevsky a household name, and he did the same for her.

Constance went to Russia twice. The first visit was in winter, and she described “shaggy ponies so prettily harnessed and everywhere the delicious sound of metal on the frost like the clink of skates.” People wore such voluminous clothes that she found it hard to tell a man from a woman. She saw great poverty—“the white weak faces”—and later wrote to The Times asking what could be done to help starving Russians. She read Russian much better than she spoke it and could have only a basic conversation.

When she took on Chekhov he was barely known outside his own country despite his fame at home. Garnett had tried to get someone to publish Chekhov in English and nobody would—imagine that her typescript of The Cherry Orchard languished in the drawer of her settle for many years. Characteristically, she kept at it until she achieved success. During the war years she translated seven volumes of Dostoyevsky. The man had been dead for a quarter of a century and many Russian intellectuals considered him their greatest novelist, but again, virtually nobody had heard of him in the English-speaking world.

Garnett made Dostoyevsky a household name, and he did the same for her. Ernest Hemingway was one of many who admired her Dostoyevskys, as well as her Tolstoys. “I remember,” he told a friend, “how many times I tried to read War and Peace until I got the Constance Garnett translation.” Not everyone shared his opinion. One critic described her Chekhov as a Victorian death rattle. Nabokov jumped in to damn her versions. But compare his translation of Gogol’s sleighbells in Dead Souls to Garnett’s. Chudnym zvonom zalivayetsya kolokolchik becomes:

Garnett: “The ringing of the bells melts into music.”

Nabokov: “The middle bell trills out in a dream its liquid soliloquy.”

Who, do you think, has the tin ear?

Like many sickly children, she carried on for decades—in her case until she was 85, long outlasting her healthier siblings. Her work has stood the test of time. I love her, and I love her stuff. She had been weaned on the great English Victorian novelists, and she has their ear for language. Equally at home with the playful and the serious, Garnett always seems to strike the right note. “Groholsky embraced Liza,” she begins Chekhov’s short story “A Living Chattel,” “kept kissing one after another all her little fingers with their bitten pink nails, and laid her on the couch covered with cheap velvet.” She certainly worked too fast and there are mistakes, but it must be the spirit that counts.

When I read Garnett’s translations I feel I am responding to paragraphs penned by Turgenev and Tolstoy themselves, not to someone else’s version of them. Her work gives the lie to Cervantes’s assertion that reading a translation is like looking at a Flemish tapestry from the wrong side: Although the figures are visible, they are obscured by bits of thread.

When I read Garnett’s translations I feel I am responding to paragraphs penned by Turgenev and Tolstoy themselves.

Garnett lives on, of course; like all writers she speaks from beyond the grave. In the early 1970s she featured as the main character in the satirical play The Idiots Karamazov, which was premiered at the Yale Repertory Theatre. A young actor named Meryl Streep played Garnett. It was a piece about the pitfalls and complexities of translation: The Russian for “hysterical homosexual,” according to the fictionalized Garnett, was “Tchaikovsky.”

*

What is the nature of translation? Is it fidelity to words on a page? Or fidelity to tone? Both, but the translator must serve the interest of the reader first and foremost, rather than working as a slave for the writer. It is sometimes said that in order to convey atmosphere a translation must be redone for each generation. But I like Louise and Aylmer Maude’s 1930s versions of Tolstoy because they are period pieces in themselves. Take this from “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”:

At the entrance stood a carriage and two cabs. Leaning against the wall in the hall downstairs near the cloakstand was a coffin-lid covered with cloth of gold, ornamented with gold cord and tassels, that had been polished up with metal powder. Two ladies in black were taking off their fur cloaks.

Compare this with a modern translation:

At the entrance to Ivan Ilyich’s apartments stood a carriage and two cabs. Downstairs, in the front hall by the coatrack, leaning against the wall, was a silk-brocaded coffin-lid with tassels and freshly polished gold braid. Two ladies in black were taking off their fur coats.

This version loses the old-fashioned “cloakstand” in favor of “coat-rack,” “cloth of gold” in favor of “silk-brocaded,” and “metal powder” goes altogether. Of course, nobody knows what metal powder is these days, but the mention of it conjures a lost world, one in which parlormaids knelt for hours polishing coffin lids. And while we know what fur coats are, fur cloaks better convey us to Tolstoy’s Russia.

The modern translation is, like the Maudes’ version, a collaborative effort, in this case by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. This pair were and are the subject of the great Russian-to-English translation punch-up of our time. Pevear, an American poet, writer, and translator from various European languages, was living in Manhattan in the 1980s with his wife, Volokhonsky, a Russian émigrée. Pevear began reading a translation of The Brothers Karamazov. Looking over his shoulder, Volokhonsky criticized what she knew to be errors. So they set about making their own Karamazov. A collaboration began, back and forth between the two of them, and a domestic industry was born. They won prizes. They appeared on Oprah (seriously) after the star selected their Anna Karenina for her bookclub. Sales soared. But what a fuss.

Correspondence raged in the pages of literary journals, academics and other suspects accusing Pevear and Volokhonsky of a “deplorable” return to the translations of old which relied too literally on the text (glossism—“the practice of enforcing word-for-word translations of English idioms on Russian prose”), with nastiness all around. An article in Commentary magazine was titled “The Pevearsion of Russian Literature.” You can sometimes see what the critics mean. Compare the following lines from Anna Karenina:

Garnett: “All his efforts to draw her into open discussion she confronted with a barrier that he could not penetrate, made up of a sort of amused perplexity.”

Pevear and Volokhonsky: “To all his attempts at drawing her into an explanation she opposed the impenetrable wall of some cheerful perplexity.”

Virginia Woolf worked in the same collaborative way with a native speaker, in her case S. S. Koteliansky—their names appear alongside each other on the title pages of their books. Samuel Solomonovich, known as Kot, had met Woolf and others in the ghastly Bloomsbury set in 1917. Five years later Woolf published her third novel, Jacob’s Room. It was a turning point in her career. But three weeks previously she had published, with Kot, a translation of suppressed sections of Dostoyevsky’s Demons as well as other Dostoyevskiana. It was the first of three Russian translations Woolf published. She knew little Russian. “I scarcely like to claim that I ‘translated’ the Russian books claimed to me,” she told a student planning a book on her own oeuvre. “I merely revised the English of a version made by S. Koteliansky.” In his obituary of Kot, Leonard Woolf, who also collaborated with the Russian, described how Kot “would write out the translation in his own strange English and leave a large space between the lines in which I then turned his English into my English.”

—————————————————

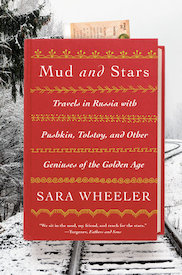

From Mud and Stars by Sara Wheeler. Copyright © 2019 by Sara Wheeler. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Sara Wheeler

Sara Wheeler is the author of many works of nonfiction, including Terra Incognita: Travels in Antarctica, The Magnetic North (winner of the Banff Adventure Travel Prize), and Travels in a Thin Country. She contributes to a wide range of publications, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Vanity Fair, and The Daily Telegraph, and broadcasts regularly on BBC Radio. She lives in London.