The Weird and Wonderful Art of Edward Carey

The Author of Little on Seeing His Characters Fully Formed

I always draw the characters I write about—it’s my way of getting to know them properly. Sometimes the drawing challenges the writing, and then I make the appropriate textual adjustments. For my novel Little, which has taken me 15 years to complete, I drew, painted, and sculpted. I knew it would take me a long time to get it right and I felt I had to throw everything I had at it. I tried to see the world as Marie Tussaud saw it, not only with her pen but also with her pencil.

Oil painting of Marie Grosholtz (the future Madame Tussaud) painted by Jacques Louis David

Little was a long time in the making. Early on, I knew I had to include the greatest painter of the French Revolution, Jacques Louis David. His portrait of Jean Paul Marat murdered in his bathtub is an astoundingly disturbing piece of propaganda. Tussaud’s own waxwork of Marat was, she said, David’s model for his famous painting. Her waxwork shows a very ugly, pockmarked man just after death, eyes and mouth wide open. David’s shows a martyr, a beautiful man lying still—a Christ-like figure.

David was Robespierre’s primary propaganda man. After Robespierre’s execution, David was thrown in prison, where he painted a self-portrait in which the tumor upon his face (which he’d had since youth, and which twisted his face and affected his speaking), was almost entirely invisible.

In Little, Marie visits David while he’s in prison and David paints a portrait of her. A few weeks into work upon this piece (I studied David’s paintings and technique as best I could), I began to think that Marie wouldn’t like to have herself so observed—she was used to taking people’s likenesses, not the other way around. I obliterated most of the painting and started again, this time with Marie’s hand over her face. She didn’t want David to know her.

From the experience of painting this fake David, I realized that although I would put Marie’s drawings in the book, I would never reveal her image to the reader—all the pictures of her show her from behind or in the shadows. I hope the novel itself, and the pencil drawings that are inside it, add up to a fully formed portrait.

In prison David swore that he would never involve himself in politics again, that henceforth he would only paint portraits of ordinary people. He lied, of course, and went on to paint more beautiful lies for Napoleon.

Wax death mask of Doctor Curtius

To understand the process of making waxworks—to properly comprehend the feel of wax, and the smell of it, how to heat and how to color it—I felt I needed to work with the medium myself. There are wonderful wax self-portraits of Marie Tussaud at the museum in London (what an extraordinary, tiny, wise, and strange-looking woman she was in old age—she resembles Babayaga, or the witch from Hansel and Gretel, or one of Brueghel’s folklore characters), but there aren’t any of Doctor Curtius, the man who trained her. Curtius was an expert in wax anatomy and was clearly brilliant at his profession. There’s a wax bust that might be of him in the Musee Carnavalet in Paris, but it hasn’t been confirmed (and in fact that face is rather a dull one). I wanted Curtius to have striking looks, to be extremely thin so that he almost looked like an artist’s écorché model (in which the skin of a human is stripped away to reveal all the muscles beneath).

When Curtius dies towards the end of Little (leaving all his possessions to Marie, which he did in real life—although there were considerable debts), her first instinct is to make a death mask of him. So I tried to do that, too. I made Curtius’s death mask in clay, made a mold from that, and then cast it in wax. I was trying to learn both the process and the character simultaneously. A sketch of Curtius’s death mask appears in the novel.

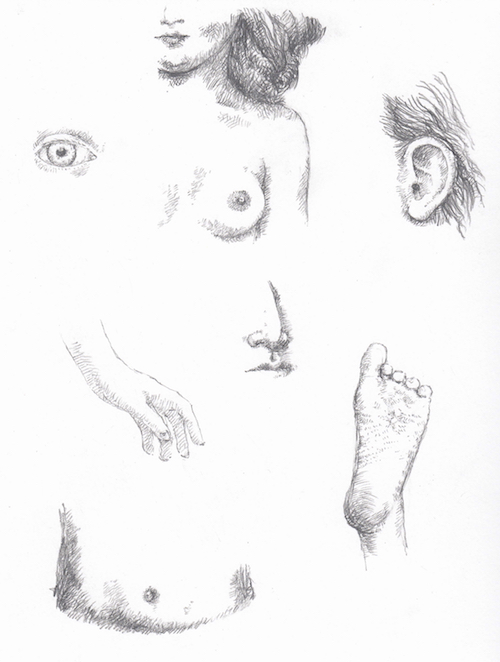

Intimate sketches of Princesse Elisabeth

I wanted to show different styles of Marie’s drawings in the novel. Sometimes, for example, she gives us straightforward illustrations of the tools she works with, but other times her sketches reveal more intimate subjects—and, hopefully, by their tenderness, reveal something more about Marie’s personality.

In Little Marie falls in love (not necessarily fully reciprocated) with two characters—one male, one female. The woman—Elisabeth, Louis XVI’s youngest sister—was a rather neglected member of the Bourbon family. Madame Tussaud stated that she was employed as Elisabeth’s sculpture teacher (but this has never been convincingly substantiated) and that she looked very much like Elisabeth (indeed, she did). In the book Marie becomes intimate with Elisabeth by working for her, and sketches small parts of her, little observations—a portrait that only Marie could have made.

Small bust of Edmond

The other character Marie falls in love with is a young man, Edmond, who at first sight seems a very bland person, barely noticeable at all. He’s particularly in the shadow of his domineering mother, who supplies the tailor’s dummies that Curtius puts his wax heads upon to make complete figures. Edmond serves as the model for all of his mother’s tailor’s dummies. But Marie studies this seemingly cloth young man and comes to love him; his ears, she says, are the most eloquent she has ever known. In time Marie and Edmond begin to meet clandestinely, but Edmond’s mother has ideas of marrying him off to the owner of a Parisian printworks. Marie, forbidden access to Edmond and heartbroken, secretly models small clay sculptures of him, stealing all of the necessary materials. Edmond’s mother discovers the sculptures and smashes them all.

Wooden woman

Marie is not the only character to make models of her absent love. Cut off from Marie and from the rest of the world, and living in distress in an attic, Edmond carves a likeness of her out of joists and beams from his unhappy home. This full-length doll (a little over four feet—Marie’s height) is a character in its own right. I made her very early on in the writing process. Her arms and legs have joints; her clothes were found in flea markets in Paris (where I spent months doing research for Little); her brown glass eyes were found second-hand in a shop in Prague; her hair was kindly donated by my wife; her head was carved out of an old telegraph pole in Ireland; and the rest of her came from bits of wood around an old Georgian house in the process of being restored. This life-size doll sits at home with us, taking up the same amount of space as Madame Tussaud once did.

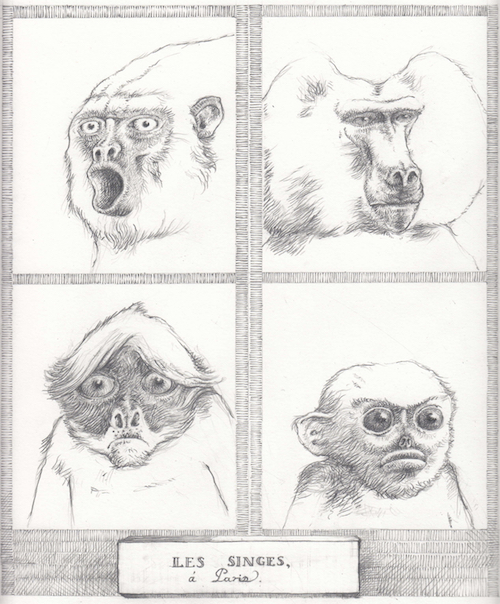

Monkeys

Animals crop up throughout Little: Louis XVI shoots feral cats from the rooftops of Versailles (based on historical fact); Josephine de Beauharnais, Napoleon’s future empress, is visited in prison by her pet pug (also true); when Marie finds drawing human deaths too painful, she substitutes dead animals for the victims (a dead woman in the street is substituted with a dead rat; her mother’s corpse is explained by a drawing of a hanging wood pigeon).

A great deal of the action in Little takes place in the Monkey House, where various breeds of monkeys were exhibited to curious Parisians; the monkeys died off one by one and the business ultimately failed. Waxwork humans now take the place of the monkeys in the halls, but the smell of the monkeys still permeates the building, the monkeys’ scratch marks still on the walls. Marie, who believes the building is haunted by the monkeys’ ghosts, hears them at night scampering along the corridors, sometimes screaming.

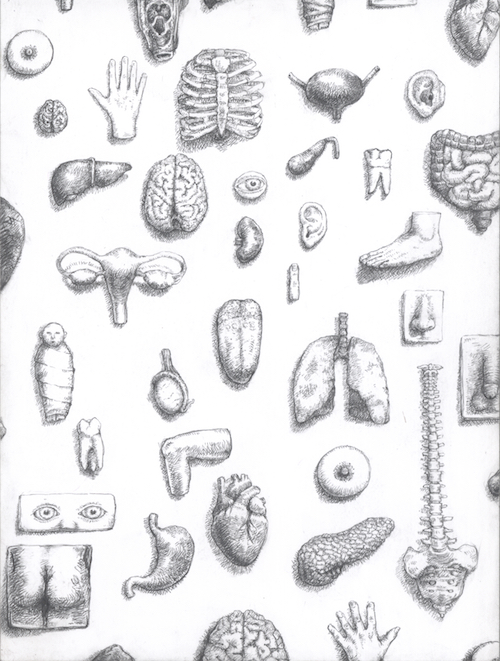

A page of wax organs

A page of wax organs

This illustration was one of the most challenging to get right, and I thought I might never finish it. When Marie is with Elisabeth at Versailles, the pair decide to make votive wax objects of the poor and suffering people around the palace estate. By the end of their time together, they’ve filled the nearby church of Saint Cyr with all of the wax organs.

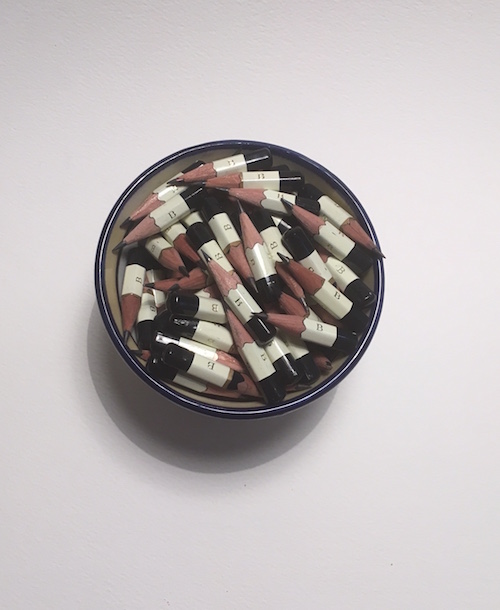

Pencil stubs

Pencil stubs

I used the same type of pencil for all the drawings in Little: Tombow type B from Japan. They run a little darker than most brands, and are quite ideal—you can get shades from the darkest dark to quite light out of a single one. I was going through them at a rather worrying rate, but was then introduced to the pencil extender, with which you can use a pencil right down to its very end. I think the stubs are beautiful, so I’ve kept them all!

Edward Carey

Edward Carey is a novelist, visual artist, and playwright. His previous novels include The Swallowed Man (a New York Times Editors' Choice), Little, Alva & Irva, and Observatory Mansions, and an acclaimed series for young adults, the Iremonger Trilogy. Born in England, he now teaches at the University of Texas in Austin, where he lives with his wife, Elizabeth McCracken, and their family.