The Vulnerable Private Writings of Ernest Hemingway

Sandra Spanier Considers the Archive of an Icon

I can trace my passion for Hemingway to a sweltering July afternoon in Key West in the 1970s. My husband and I were there with a couple of friends who were eloping. We were the sole witnesses to the wedding, conducted in the office of the justice of the peace, who, upon learning the purpose of our visit, walked over to a hook on the back of his door, removed the necktie hanging there and put it on over his golf shirt. After the ceremony we had lunch at a fish shack, and as I was already too sunburned to think about the beach, we headed for the Hemingway House.

I don’t recall seeing any other visitors. In the living room the high French doors were open to the veranda, and a cat was napping on the sofa. In the kitchen another cat had draped itself across the top of the stove. The guide invited us to take a cat home if we wanted to—they were special six-toed “Hemingway cats,” he said, but it didn’t seem practical. (We know now, thanks to the recollections of the author’s son Patrick Hemingway, who grew up in that house in the 1930s, that despite the present-day hype, the family did not have cats on the property, but kept peacocks instead.) We walked through the rooms, up the center staircase, around the house on the outside balcony, and across a catwalk to the room on the second floor of the coach house, where Hemingway retreated to write.

As a fellow midwesterner (a native of Des Moines, Iowa, a few hundred miles due west of Hemingway’s hometown of Oak Park, Illinois), I felt the lure of the exotic: the turquoise waters of the Gulf, faded old wood houses with gingerbread trim, turtle soup and conch chowder, the sign saying “Southernmost Point of the United States—90 miles to Cuba.” My interest in Hemingway was piqued, and I began reading everything he had written.

If I had to identify one thing that most strongly attracted me to Hemingway—and attracts me still—it probably would be his art of evoking a sense of place. Henry James—not one of Hemingway’s favorite writers—advised those who aspired to write fiction, “Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost.” As a writer who started out as a journalist, Hemingway had a sharp eye and keen ear. His letters capture his own immediate impressions and excitement of discovery as his world widened out from the American heartland.

In May 1923, encouraged by Gertrude Stein, Hemingway traveled to Spain to witness his first bullfights. He was immediately enthralled. Just weeks after returning home to Paris in mid-June, he headed back to Spain with his wife, Hadley. On July 18th, 1923, he wrote to his ambulance corps comrade Bill Horne, “Have just got back from the best week I ever had since the Section—the big Feria at Pamplona—five days of bullfighting dancing all day and all night—wonderful music—drums, reed pipes, fifes—Faces of Velasquez’s drinkers, Goya and Greco faces, all the men in blue shirts and red handkerchiefs—circling, lifting floating dance. We the only foreigners at the damn fair.” He described the morning running of the bulls through the streets, from the corrals on the edge of town into the bullring, “with all of the young bucks of Pamplona running ahead of them!” Of the bullfight itself he wrote, “It’s a great tragedy—and the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen and takes more guts and skill and guts again than anything possibly could. It’s just like having a ringside seat at the war with nothing going to happen to you.”

Hemingway returned to Spain the next two summers for the Festival of San Fermín, and immediately after the 1925 Festival ended, he began a novel, writing in French school notebooks and completing a draft in ten weeks. Because of that novel, The Sun Also Rises, published in 1926, “foreigners” by the tens of thousands throng to Pamplona every summer, drawn by the force of Hemingway’s imagination. Outside the bullring, a stone bust of the author presides over the Paseo de E. Hemingway, the street named in his honor.

Hemingway had a knack for putting places on the map. His presence is still palpable in Key West, a remote tropical outpost when he and his second wife, Pauline, arrived in 1928. Another bust of Hemingway—reputedly forged from melted-down boat propellers donated by local fishermen—keeps watch over the harbor in Cojímar, the fishing village east of Havana where he kept his beloved boat, Pilar, and set his 1952 novel The Old Man and the Sea. The Finca Vigía, his longtime Cuban home, where he lived with Martha Gellhorn from 1939 to 1944 and later with Mary Welsh, is now a national museum.

A year after my first visit to Key West, we moved to State College, Pennsylvania, where I began work on my master’s degree at Penn State, taking whatever courses were offered in the evenings and summers while teaching junior high English in the public schools. More than anything, I wanted to study with Philip Young, “Our Hemingway Man,” as he was known in the Penn State English Department—who had written one of the first books about Hemingway, published in 1952 (despite Hemingway’s resistance to being “dissected alive” by a literary critic). Unfortunately, Professor Young did not teach evenings or summers, so I arranged to do an independent-study course with him, assisting in research for his book Revolutionary Ladies, about Loyalist women during the American Revolution. I spent a summer in the basement of the library, poring over the spidery handwriting of 18th century letters on microfilm and getting my first taste of the excitement of watching history unfold through running eyewitness accounts.

A few years later, as a doctoral student, I finally had my chance to take Philip Young’s Hemingway seminar, and I asked if he would direct my dissertation. Fine, he said, but not on Hemingway. Hemingway had been done to death. There was nothing new to say about him.

I was disappointed at the time, but in retrospect I am grateful for his advice. As a result I encountered the work of one of Hemingway’s contemporaries in Paris in the twenties, Kay Boyle—a writer I had never heard of, and I had the remarkable privilege of getting to know her over the last thirteen years of her life. What began as my dissertation evolved into the first book about her, in 1986, and shortly before she died in 1992 at the age of 90, she asked if I would compile and edit a volume of her selected letters. Although she had always resisted what she considered prurient public interest in writers’ private lives, she wanted the story of her life to be on the record in her own words as an antidote to whatever distortions a future biographer might perpetrate. I jumped at the chance, of course. Little did I know that she had written more than 25,000 letters (copies of some seven thousand of them now fill my file cabinets), or that it would be twenty-four years before the volume, Kay Boyle: A Twentieth-Century Life in Letters, was finally published in 2015.

In the meantime, my interest in Hemingway never flagged, and his places always beckoned. Like countless other aficionados, a copy of The Sun Also Rises in hand, I have followed Jake Barnes’s walk through Paris from the Île Saint-Louis across the bridge to the Left Bank of the Seine, up the rue du Cardinal Lemoine, past the Place de la Contrescarpe, down the rue du Pot du Fer, and on to the cafés of Montparnasse. From Paris I have followed Jake’s trail to Bayonne, San Sebastián, Burguete, Pamplona, and Madrid, ending with dinner at the Restaurante Botín. Always there is the shock of recognition. Hemingway always got it absolutely, perfectly right. Braids of garlic are sold in street stalls during the fiesta in Pamplona, hence the wreaths of white garlic the revelers wear around their necks as they dance around Brett Ashley. I have slept in the northeast corner room of the Hotel Ambos Mundos in Havana, one floor below Hemingway’s favorite room (now a small museum). Except for a few modern architectural intrusions, the view is just as he described it to readers of the first-ever issue of Esquire magazine (Autumn 1933) in “Marlin off the Morro: A Cuban Letter.” There really are black squirrels in the woods around Windemere, the family cottage on the shore of Walloon Lake, Michigan, where the young Hemingway spent every summer of his youth—the country he made us all see in his Nick Adams stories.

My professor Philip Young would probably be surprised—and, I know, pleased—to see the vigorous health of Hemingway studies today, along with the intense, seemingly insatiable widespread public interest in Hemingway and his work.

One of the most exciting ongoing projects focuses on Hemingway’s letters. Some six thousand of them survive, and with the blessing and encouragement of Patrick Hemingway, an effort is underway to publish Hemingway’s complete collected letters in an edition projected to run to at least seventeen volumes. It is an honor for me to serve as general editor of the Hemingway Letters Project, directing an international team of scholars to produce The Letters of Ernest Hemingway, being published by Cambridge University Press.

Hemingway’s published work is painstakingly crafted, but his letters are unguarded and unpolished. They chart the course of his friendships, his marriages, his family relationships, his literary associations, and his business dealings. The letters are striking for their sense of immediacy. When he grumbles about a balky typewriter, doubts whether he has spelled a word correctly, reports the mileage on his car’s odometer or the measurements of a fish he caught, tallies the page count of a book in progress or complains of a sore throat, we are reminded that the great writer and Nobel laureate was also a human being.

Hemingway wrote in another piece for Esquire magazine, “Old Newsman Writes: A Letter from Cuba” (December 1934): “All good books are alike in that they are truer than if they had really happened and after you are finished reading one you will feel that all that happened to you and afterwards it all belongs to you; the good and the bad, the ecstasy, the remorse and sorrow, the people and the places and how the weather was. If you can get so you can give that to people, then you are a writer.”

Hemingway did not regularly keep a journal, but his letters are a vivid and spontaneous real-time record of his life and times. Hemingway’s letters capture in the freshness of the moment the people and the places and how the weather was. Taken together, they constitute the raw footage of an epic life story and a chronicle of the 20th century.

__________________________________

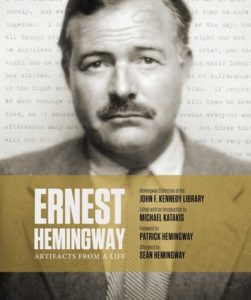

From Ernest Hemingway: Artifacts From a Life, edited by Michael Katakis. Used with permission of Scribner. Copyright © 2018 by Sandra Spanier.

Sandra Spanier

Sandra Spanier is a professor of English at Penn State and General Editor of the Hemingway Letters Project.