The Untold History of the “Asian American” Identity

Cathy Linh Che and Kyle Lucia Wu Reflect on What Led to Their Children’s Book

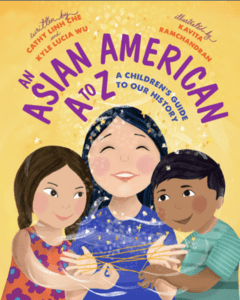

While writing our children’s book, An Asian American A to Z: A Children’s Guide To Our History, we knew where to begin: with the letter A:

“A is for Asian American! Many fought for you, and a name for us all, collective and true. Immigrants, refugees, workers, and students. To choose one name was the start of our movement.”

It’s important to start here because until the late 1960s, Americans of Asian descent were mostly called “Oriental.” Asian Americans of that time typically identified with their specific ethnic group–Chinese, Japanese, or Filipino–but not under a greater political identity.

A group of student-activists, inspired by the social movements led by Black, Brown, Indigenous, Queer, Disabled, and anti-War protesters of the time, decided to change this. They generated strength by creating a pan-ethnic coalition, and called themselves, for the first time, “Asian Americans.”

But this wasn’t a history we were aware of growing up. Though we were raised across the country from each other in very different environments, we shared something formative: neither of us had been taught Asian American history. Even today, out of over 5000 colleges and universities in the US, only 26 schools offer a degree in Asian American studies.

Our education centered “tolerance” or “celebrated multiculturalism,” but we never learned how the Civil Rights Movement had paved the way for most Asian immigration to America. We did not learn about The Asian American Political Alliance’s participation in the Third World Liberation Front, a coalition of student groups who held a four-month strike to obtain ethnic studies at their colleges. We did not know about Larry Itliong, a labor organizer behind the Delano grape strike or about Grace Lee Boggs’ and Yuri Kochiyama’s place in the Civil Rights Movement. We had to discover these histories ourselves.

I grew up aware of the racism I was steeped and strained in, but I did not have the language or knowledge of the systemic forces behind it.

In writing our new book, we hoped to create an accessible resource for parents, students, and anyone interested in Asian American history. Here is more on our individual journeys toward self-education.

Kyle Lucia Wu: Shortly after I began working at Kundiman, an organization that nurtures writers and readers of Asian American literature, we planned our inaugural Youth Leadership Intensive. We developed an oral history project where the students, all high schoolers, would interview each other and record their conversations. This is how history is formed–through archives and documentation.

The matter of whose lives are recorded in history books is always a matter of politics. Reading the conversations, I was presented with such eloquence around fears of my own–fears of authenticity, of not being “really” Asian, of being both too American and not American enough. Yet I noticed that we all thought we were the first to feel this way. I was over a decade older than the students and still bumbling through how to word a way I’d felt my whole life.

When I began seeking out an Asian American history education on my own, it was through secondhand textbooks ordered online, Erika Lee’s The Making of Asian America, and books by Grace Lee Boggs and Yuri Kochiyama. In her early twenties, Yuri Kochiyama kept getting fired from jobs as a waitress. She had spent time in an incarceration camp with her family, and after they were released, she could only stay at a job for weeks or months at a time before other waitresses complained about working with someone Japanese, and she would be fired.

She said that those experiences made her aware of racism, but that she was still years away from a political awakening because she didn’t yet have the understanding of the politics behind why racism occurred. It was a resonant moment for me; I grew up aware of the racism I was steeped and strained in, but I did not have the language or knowledge of the systemic forces behind it, or even the idea that it was a collective experience. Without any inkling of the expansiveness of Asian American lives, I was left blinking only at the dimly-lit knowledge of how it had affected me.

The histories of oppressed people have always been subject to erasure.

It seems by design that our history books have lacked Asian American history. It keeps the lights of awareness at a soft glow; it keeps us starting from the beginning, and feeling alone in the process. Writing this book with Cathy was a joyful and collective experience in which we drew from each other’s knowledge and called on our community to guide us–each of us adding the lantern we can, to brighten the starting point for all.

Cathy Linh Che: I was born in Los Angeles five years after the end of the Vietnam War to refugee parents who’d been among the first to escape Vietnam. I grew up among others who shared the same language, the same food, the same social and economic class, and the same story. I lived and went to school with Black, Latinx, Asian, and Pacific Islander neighbors and community members. Despite an upbringing steeped in interracial belonging, my formal education taught me very little about Asian American history, and what I learned was patchy at best.

My first Asian American history lesson occurred when I was 32 years old. Timothy Yu, a poet and an Asian American Studies scholar, led an Asian American poetry seminar at the Kundiman Retreat. This is when I learned about the poems carved into the barracks at Angel Island by Chinese detainees, the political poems of San Francisco poet laureate Janice Mirikitani, the poetry folios present in the earliest Asian American publications.

That one-hour session felt revelatory to me and urged me to investigate the ways that writing, history, and activism intersected. Kyle shared her copy of The Making of Asian America with me, and I spent the pandemic reading Karen L. Ishizuka’s excellent Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties.

While co-writing this children’s book, Kyle and I also reached out to readers whose identities were different from our own, which helped us continue our Asian American history education beyond the books we’d read. I’m grateful to Summer Farah, who taught me about the solidarities between Black and Arab auto workers who fought together for a free Palestine, and to Swati Khurana, who informed me about Kala Bagai, a South Asian activist and community builder who now has a street in Berkeley named after her.

Craig Santos Perez encouraged us to share activist calls from Pacific Islander communities and to lift up the importance of Asian American allyship. Though my knowledge is limited, it continues to grow, and I am proud to be able to share with others what we’ve learned thus far.

Near the close of our book, Y is for Yuri Kochiyama, who said: “Remember that consciousness is power. Tomorrow’s world is yours to build.” The histories of oppressed people have always been subject to erasure, and the attack continues today. Schools are banning books written by, for, and about marginalized people across the country. Understanding the power that came with our own self-knowing, we wrote this book for all those who are building our tomorrow.

__________________________________

An Asian American A to Z: A Children’s Guide To Our History by Cathy Linh Che and Kyle Lucia Wu, illustrated by Kavita Ramchandran, is available from Haymarket Books.

Cathy Linh Che and Kyle Lucia Wu

Cathy Linh Che is a Vietnamese American writer and multidisciplinary artist. She is the author of Split (Alice James Books), winner of the Kundiman Poetry Prize, the Norma Farber First Book Award from the Poetry Society of America, and the Best Poetry Book Award from the Association of Asian American Studies.

Kyle Lucia Wu is the author of the novel Win Me Something (Tin House Books 2021). Kyle teaches creative writing at Fordham University and The New School. Previously, she was the party correspondent at Literary Hub.

Kyle has received the Asian American Writers’ Workshop Margins fellowship and residencies from the Byrdcliffe Colony, the Millay Colony, Plympton’s Writing Downtown Residency, and the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center.