The Unsettling Sea: On Rationalizing the Drowning of the World We Inhabit

Patrick Nunn Investigates Climate Change Denial and the Truth About Our Rising Ocean Levels

In the final encounter between Captain Ahab and the white whale he named Moby Dick, the Captain repeatedly harpoons the whale, but the rope becomes entangled about the Captain’s neck and he is carried off into the depths of the Pacific. The fate of the beast and the man entwined in death as it had become in life. The whale also holed Captain Ahab’s ship, the Pequot, causing it to sink with all its crew. Bobbing in the water, Ishmael, the sole survivor, described the aftermath.

…small fowls flew screaming over the yet yawning gulf; a sullen white surf beat against its steep sides; then all collapsed, and the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled 5,000 years ago.

There is something unsettling about the sea. We often describe it as limitless, as a power we cannot ever hope to subdue. We accept its peregrinations, we bow to its majesty. As we saw in Chapter Four, until quite recently in human history, it may be that drowning people were never saved by others who feared this was to deny the ocean its due. Sometimes drowning people were even encouraged by onlookers to cease their struggles and accept their fate, the sea’s life-ending embrace. How outrageous such sentiments seem in today’s world… yet they do illustrate people’s recently changed relationship with the ocean, a change underwritten by our hugely improved understanding of the watery parts of the planet.

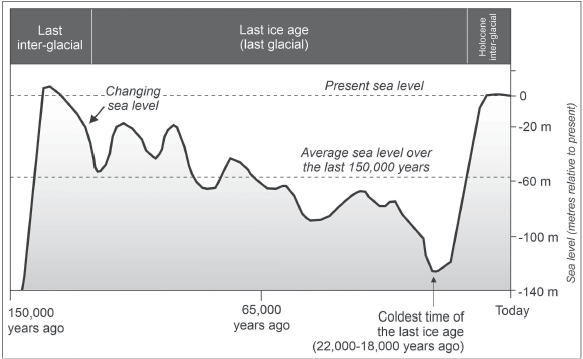

We inhabit a drowned world. Science has shown this to be true beyond doubt. Within the last two million years or so, even just the last 150,000 years, the average level of the ocean surface has been some 50–60m below what it is today (Figure 8.1).

Yet do not imagine for one moment that science was first to uncover this fact for, as we saw in previous chapters, our ancestors lived through times when the ocean surface was lower, at times more than 100m lower, than today. They survived its rapid post-glacial rise but not without both discomfort, as shown by the surviving stories of displacement and involuntary adaptation from the fringes of ice-age Australia and Kumari Kandam, and inconvenience as manifested by the evidence of submerged coastal cities, from 5,000-year-old Pavlopetri to even possibly earlier ones like Cantre’r Gwaelod and Ys. It seems reasonable to suppose that the fragments of ancient stories and myths that have reached us today represent memories of times when the ocean surface was much lower than it is today.

Figure 8.1: Changes in the ocean surface over the past 150,000 years.

Figure 8.1: Changes in the ocean surface over the past 150,000 years.

We may privilege the comforting rationalism that science provides about past sea level changes, but there is no question that knowledge about these from millennia-old eyewitness accounts was available to us far earlier. So overgrown were these accounts with the vines of narrative embellishment that we failed to recognize them for what they were. But perhaps, just perhaps, in some obscure set of synapses in the rafters of our brains, ancient memories linger about times when the sea level was so much lower. Memories we might one day dust off and activate to help us rationalize the renewed drowning of the world we inhabit.

Over long time periods—centuries, millennia and more—the ocean surface has rarely been static. It is not difficult to understand why. A bucket of water, a swimming pool, a lake, the world’s ocean— the principles are the same. If you add more water, the water surface rises. If you throw a few stones in the bucket, 50 people in the swimming pool, a mountain or two in the lake, or extrude a line of volcanoes along the floor of the ocean, the water surface will also rise because the capacity of the container has been reduced. All that pretty much explains why many lands, once occupied by people, have become submerged. Either the ocean had more water added to it… or its water-holding capacity was reduced. Sometimes both things happened together.

Over the past 200 years or so, the sea level has been observed to be rising along many coastlines. The vehemence with which some people deny this to be the case may give you pause for thought, but you should not be fooled. Such people are generally far less interested in what is happening because of the inconvenience this represents, given who they are and what they do. It may be that a person’s investment in a cliff-top or beach-back mansion is threatened by sea level rise, but that is not an easy thing to blame, let alone from which to argue for compensation. Far better to deny that sea level is rising and blame the authorities for some supposed oversight that is apparently having the same effect.

The vehemence with which some people deny this to be the case may give you pause for thought, but you should not be fooled.

More common among deniers of sea level rise is the idea that it cannot be happening because climate change is assuredly a myth, a ruse cooked up by economic aggressors or unprincipled researchers to improperly advantage themselves. I often hear such complaints first hand. But at the end of the day, the cause is less important than the effect, something of which people sometimes lose sight. For there is no question that sea level is rising—a global average of three to four mm every year currently—and we cannot logically deny that fact because we are skeptical about its possible causes.

*

If we ignore the short-term oscillations of the ocean surface, like the daily journey it makes between low and high tide, then it has an average level known as “mean sea level.” During the last great ice age, around 20,000 years ago, averaged across the planet, mean sea level was around 120m lower than it is today. This was because so much water had been sucked out of the oceans to build massive land-based ice sheets that smothered many northern hemisphere continents at this time. Not literally sucked, of course. It is just that in most parts of the world today, when ocean water evaporates and then falls on the land, it does so as rain, which gets into river systems and finds its way back to the ocean where the cycle starts all over again.

But imagine if it were so much colder on land that the evaporated water fell there not as rain, but as snow or even ice. That snow and ice could not easily find its way back to the ocean so it accumulated on the land, eventually causing the ocean surface to start dropping. This explains why the ice ages were times of comparatively low sea level and the times between them, commonly known as inter-glacial periods, were times of comparatively high sea level—like that we live in today.

A few years back, before scientists began talking about the Anthropocene, the age in which human influences on the Earth’s climate have become dominant, it was the Holocene inter-glacial in which we lived. A time of anomalous warmth and unusually high sea level, which, while not without precedent, was clearly not the average condition of the Earth during the 200,000 years or so of its modern human residency. It is a conceit to think otherwise, unfortunately a conceit that lay unquestioned for many years at the foundation of modern geoscience and its bibliolatrous roots and which informed early understandings of how the recent history of our planet unfolded. The legacy of this belief lives on in the reluctance of science over the past 50 years to accept and then embrace the manifest evidence for global change. Today, there is an overwhelming scientific consensus about the fact of our rapidly changing world, but just a few decades ago some respected scientists were dreaming up convoluted explanations as to why this was not the case.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Worlds in Shadow: Submerged Lands in Science, Memory and Myth. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury Sigma, an imprint of Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2021 by Patrick Nunn.

Patrick Nunn

Patrick Nunn received a PhD from the University of London before spending 25 years teaching and researching at the University of the South Pacific, where he was appointed Professor of Oceanic Geoscience in 1996. Author of more than 320 peer-reviewed publications, Patrick has also authored several books, including Vanished Islands and Hidden Continents of the Pacific and The Edge of Memory.