The Two Times You Meet the Devil: On Chance Encounters With the Everyday Strange

A. Kendra Greene: “The more I think about it, the more I wonder how many times we have met... and the devil has said nothing.”

The first time I met the Devil, I was walking down a steep dirt road, with a friend, the road so steep it had taken five tries in our tiny rental car to maintain enough nerve and momentum, charging towards the decision point of a brick wall, to overcome the slope and still, cranking the wheel, take a harrowing narrow turn that was both sharp and blind. There was no other way. I don’t know how we managed. We knew mostly the failed attempt, the near miss, the tires at some intermediate spot churning pointlessly to a stall and slipping us back to where we’d started.

Our success in ascending had been so arduous and unlikely that my friend and I assumed we would never drive up the hill again, that we were on foot now, that we would forsake the vehicle where it was at the summit until we left Tilcara for good. We were walking down the hill, for the first time, still startling, the soles of our shoes slipping a little, too, and our hands periodically flung out to brace, when an old man waved us over.

I wondered later how often it happened, how often someone was asked for something so small and they broke.

The old man’s clothes were the color of the dirt road. He was missing some teeth. He had a lot to say, a lot of questions to ask, and we understood not a word. It had been a long time since I’d lived in this part of the world, and it seemed reasonable my tongue was clumsy, unable to say what it wanted, my ear cottoned, unable to parse words I should have known, but my friend was a translator by profession and having the same luck. When we could make no sense of his questions, we tried our own, but neither did the old man understand us.

It was then that a young man came up the road to meet us. The young man was handsome, had a beautiful smile, was missing a few teeth too. The young man said, “You’ll never guess what I have in my bag.”

The bag was about the size of a backpack, big enough to hold a basketball, a few loaves of bread. It would, the thought flashed before me, perfectly cradle a severed human head.

“It’s an animal,” I volunteered, and the young man laughed. “No,” he said gamely, happily, egging on the next bet.

“In that case,” I said, joking back, “it must be two animals.” “No,” he said, suddenly stern, annoyed, no longer laughing. He added, I assume both to underline his disappointment in my paltry imagination and to definitively put an end to this feeble line of inquiry, “It’s not animals.”

This was unfortunate. I had not expected, say, a bag full of kittens, but a creature of some kind still seemed one of the better possible outcomes among things that would fit in a gleeful stranger’s bag. But there was no puppy, no tiny baby goat, no pangolin curled tight in a ball. Nothing like that at all.

Now the young man was serious. Now the young man was done with guessing and games. He opened his bag in one motion, and there was such a profusion of colorful cloth, so many tiny mirrors stitched to the fabric, that my next guess was a circus tent.

“No,” the young man said, his enthusiasm returning. “This is my devil suit.”

The devil smiled. The devil was proud of this suit.

“Then why aren’t you wearing it?” I asked the devil.

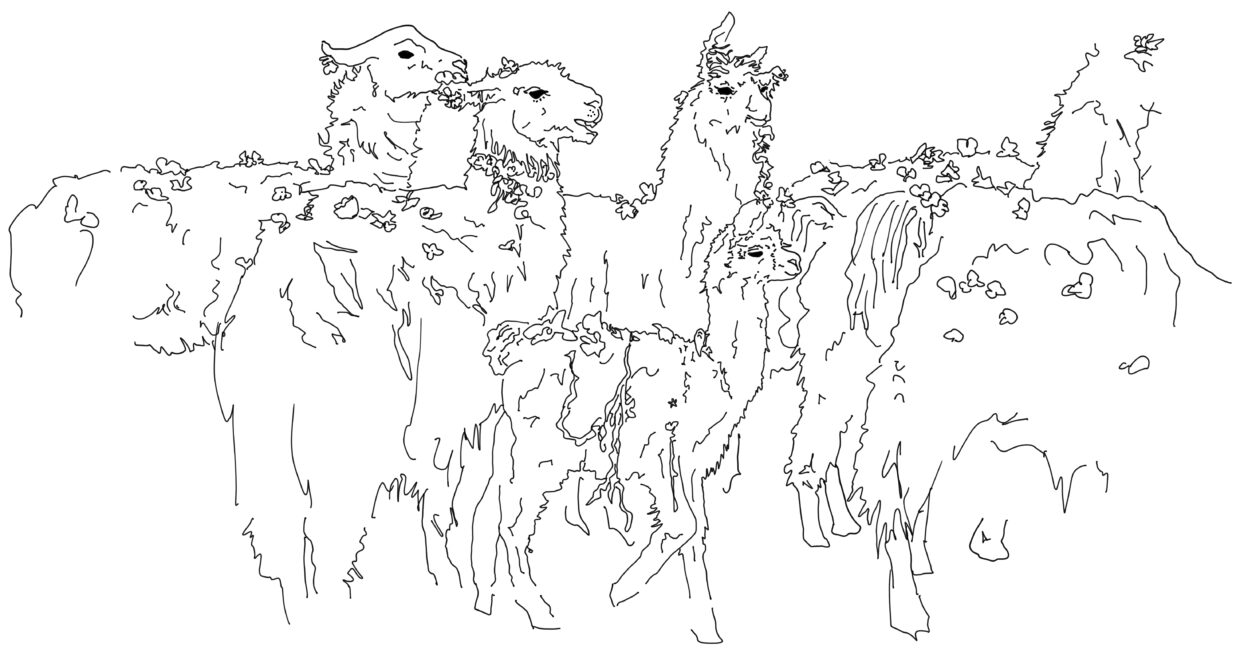

The devil explained, “I only wear it when I’m in town.” He was magnanimous now. The devil assured us, not to worry, he would put the suit on again that evening, when it was time to go back to town. It seemed the devil was needed only in town—and mostly at night—and though we were still arguably in town, within the old city walls if not the new ones, this particular spot where we’d met was perhaps far enough from the center, maybe just dusty enough or merely part of an old reckoning, not to count. From where we were standing, we could see the mountains, the main road that had brought us here from the seven-colored hills. We could not yet hear the music played in town. It was not quite time to tie flowers to the llamas and parade them through the streets.

The old man, who had said nothing while the devil spoke, now reached out to stroke my hair. Even the devil found this odd, uncomfortable. I saw it in his eyes. Without excusing ourselves, my friend and I briskly resumed our walk down the dirt road and into town. The old man may be there still, for all I know. The devil moved sprightly on his way.

*

The second time I met the Devil I was the only employee of a new bookstore that was already about to fail. It was summer. It was the afternoon. The bookstore was a brick building on a corner lot and the sun streamed through the south and west windows and everything glowed. There was an old leather couch in the middle of the room, its surface cracked and breaking, and I liked to imagine that it was plotting its escape, gradually departing on the legs of customers who sat too long, the bits of couch now fugitive freckles sweat-stuck to the backs of their thighs.

The month before, a man in recovery had come into the bookstore, a basket on his arm, selling banana bread that reeked of the plastic wrapped around each loaf. He was telling me about the ministry he was raising money for, the good works they did, and I couldn’t tell him that I actually hadn’t been paid in a while. I thought so hard about whether I could afford to give this man five dollars, of what it might mean to him versus what it might mean to me, that when I tried to speak to him, I sobbed.

The man from the ministry was not embarrassed by me. He was gentle. He seemed prepared for this. I wondered later how often it happened, how often someone was asked for something so small and they broke. The man from the ministry set down his basket and asked if he might pray.

I was standing in the very same spot the day the devil walked in. The devil announced himself immediately.

“I am the devil,” the devil said.

The devil had little to say about his origins, but he confirmed that he had been the devil for quite some time. What that entailed, it seemed, was in flux. Sometimes he got seasonal work in haunted houses. Sometimes he led tours. Foreigners, he said, foreigners especially like a tour led by the devil. At present the devil was emcee for a monthly circus burlesque, themed on the seven deadly sins, and it was in that capacity that the devil had come into my bookstore to acquire door prizes to award the audience that night.

The devil preferred to buy local, he said. The devil could have spent his money anywhere, I considered, but here he was, trying to keep it in the neighborhood.

I found I had no shortage of books to recommend to the devil. There were many independent presses I thought he might like, several specific titles. The devil had broad tastes, and he was careful in his consideration, appreciative there was so much literature in translation. He read from everything I brought him and, mindful of his audience, finally settled on a thin volume of drawings, crude in both style and subject, and funny as they were dark.

The devil was nothing but patient as I mustered up something resembling gift wrap. We had never gotten around to ordering it, could never justify the expense, so I did what I could with scraps of good paper and a rubber stamp. He didn’t mind. The devil seemed to have all kinds of time.

I used to think I could not write about the Devil—not until we met for a third time. There’s rhetoric in threes.

He talked at length about neighborhood history and photography and music he liked. He suggested I come by the burlesque some night. And all that time I was with the devil, no other customers walked in. No bits of shattered couch attached themselves to depart on the back of his black jeans. After I had done all I could with the wrapping, I handed the devil the thing he had come for, and the devil paid in cash.

*

I used to think I could not write about the Devil—not until we met for a third time. There’s rhetoric in threes, I thought. Meaning. Three is the difference between coincidence and a pattern. The number seemed to matter. I mean, isn’t the devil like that?

It’s not that I’ve since grown impatient. And it’s not that I’ve despaired of meeting him once more. It’s just I’ve come to think it doesn’t matter.

The devil, in these encounters, had been very forthcoming. It’s charming, I think: the devil in broad daylight, the devil running errands, the devil so delighted he cannot keep his joy to himself. Does that not have meaning of its own? I love the way the devil announces himself. How disarming! And it’s these times I’ve met the devil, these times he’s introduced himself, that led me, for a while, to assume that that is how it is. That that is how it always is.

But the more I think about it, the more I wonder how many times we have met, crossed paths at least, exchanged a look, and the devil has said nothing. Isn’t the devil like that, too?

__________________________________

Excepted from No Less Strange or Wonderful by A. Kendra Greene. Copyright © 2025. Available from Tin House.

A. Kendra Greene

A. Kendra Greene is a writer and book artist. She is the author and illustrator of The Museum of Whales You Will Never See. Her work has come into being with fellowships from Fulbright, MacDowell, Yaddo, Dobie Paisano, and the Library Innovation Lab at Harvard.