The Trauma and Violence That Black Women and Girls Endure on the Corners

Shanita Hubbard on the Erasure and Dismissal of the Emotional Toll of Sexual Harassment

There aren’t many safe spaces for Black women and girls in the United States. Many spaces that offer a level of safety and comfort to Black boys and men offer far less of it to us. This is especially true of the corners in our own community. Whether you live in the Midwest or Brooklyn, there exists a universal experience for Black women on the corners in our hoods. The street corners for many Black men are where they found brotherhood, manhood, or safety, and it’s evident in hip-hop songs and videos like “The Corner,” a stand-out track on Common’s album Be, where that is celebrated.

But for Black women and our bodies, we have a complicated relationship and experience with those corners that has been invisible in our music and often ignored within our community. Songs like “The Corner” don’t acknowledge the trauma and violence that Black women and girls endure on these corners. The juxtaposition of the experiences of Black women and men on these corners is symbolic of a larger community weak spot.

I love Common as an artist. Common is one of the most conscious rappers in the industry, and he loves Black women. However, that doesn’t negate the fact that his song, which captures the experiences of a lot of Black men with nuance and care, could have been more powerful if it included a candid look at what Black women experience on corners. Especially considering the sexual violence, antagonism, and assault Black women face on these corners, which remain largely unaddressed in our own communities.

It’s easy to consider the erasure of our perspective from “The Corner” as just another artist making a song to simply celebrate a space that’s culturally relevant to our men, without noting why including Black women in this narrative is important. That would be fine if the space in question was their “sacred” barber shop and not an unavoidable element in our community where walking by just to go home can mean being chased and assaulted by the very men who should be protecting you.

Black women need to make known the inner and emotional toll that we face. We have been constantly called out for our supposed tough exterior shell and given labels like “angry Black woman.” However, for some Black women, this tough exterior shell was developed as a coping mechanism at a young age when we had to learn how to escape sexual advances from grown men while walking through our own neighborhoods.

There aren’t many safe spaces for Black women and girls in the United States. Many spaces that offer a level of safety and comfort to Black boys and men offer far less of it to us.

The corners are a complex space in our community; in many cases, it’s the origin for unaddressed trauma in both Black women and men. There has been awareness in our music about the harm to Black men—hunted by the police, profiled, wrongfully arrested, and more. But it’s on these same corners that Black men have often hunted us and inflicted harm on Black girls and women. The corners are a space where police can snatch a brother’s freedom and inflict pain on their bodies and force a massive community outcry.

It’s also the space where police have inflicted sexual violence against poor Black women and girls without impunity. Within our community, and by extension in hip-hop, these dualities are not unpacked enough. To unpack them, we have to tell a fuller story about those corners, a story that centers on the mute experiences of Black girls and women. We have to reflect on how this later impacts our love lives as women and the tropes we contend with, and even how we learn to compartmentalize sexual violence.

Common was not the only rapper to use a video and song to paint a picture of the corners that could’ve been more powerful if the lens was broadened. Jay-Z, one of hip-hop’s best storytellers, illustrated this in his video for “Where I’m From” and walked us through the blocks of pre-gentrified Brooklyn in “Hard Knock Life.” From the corners of Chicago to the blocks in Brooklyn, the images all reflect dice games, crowds of men in front of a store, shit-talking, laughing and the police always present. There is no shortage of videos capturing the universal experiences of Black men on these corners. With few exceptions, the same can never be said of the experiences of Black girls and women.

In the video for “The Corner,” a group of young girls are dismissed from school and walk toward the corner. The scene fades and the viewer never sees what happens to those girls. This is exactly what our missing narrative feels like in hip-hop—we know Black women and girls are present on those corners, but our stories are rarely fully explored. But if they were fully explored, listeners would understand that for a lot of Black girls, the first place they encountered sexual violence is from the older men in the neighborhood. It’s the place where men publicly expressed an interest in their bodies. If these stories were ever fully told, listeners and viewers would learn that these corners are also a place where too many Black girls get used to this treatment, and it was not by choice but because of consistency.

The corners are a complex space in our community; in many cases, it’s the origin for unaddressed trauma in both Black women and men.

It started for me when I was maybe twelve years old, but it could have been before then. According to the dudes on the corner, I was “stacked like a grown woman.” Mentally, I was far from a grown woman; I still played with dolls at home. At the time, the most exciting aspect of life was my newly acquired freedom to walk unaccompanied to visit my cousins Tonia and Vonnie, to do things like roller-skate up and down the block, or to go see my girlfriend Mika so she could flat-iron my hair. My cousins and girlfriend lived in the same hood, so I would pass the same corner. I took the same route that was always interrupted by the same group of guys.

There was never just one of them there. They rolled in droves. Some days, they’d scream things that they would do to my twelve-year-old body. I learned to walk faster. I would lower my head to make myself invisible. It didn’t matter if I crossed the street away from where they stood or walked directly by them, they would make sure I heard them. I tried to shrink myself and cover my body, or wear things that were less revealing, but that didn’t work. Soon I’d just walk by as if I didn’t hear them. As a preteen, I learned that sexual harassment from grown men went by quicker if I pretended it wasn’t happening.

Most days I wasn’t afraid of them, I was embarrassed. I didn’t become afraid until I knew they intended to make good on some of the promises they screamed. One day, the loudest man of the bunch interrupted his trash-talking with his friends and approached me. He knew my name, knew exactly where I was coming from, and even mentioned my older brother. “What’s up lil Rome, you coming from Mika’s house today?” I glanced up at him slowly. He was a large man, six foot three and stocky, eclipsing my five-foot-six, twelve-year-old self.

He was handsome, with dark chocolate skin and wavy hair that I’m sure did him well in the ’80s. He was in his late twenties and seemed to be popular with the other guys. A small part of me was flattered by the attention when he approached me, but I was still uncomfortable. He was “old.” I was confused about why he would even look at me, much less approach me, especially since he knew my brother. I was annoyed at myself for not crossing the street fast enough and hoped he’d leave me alone. The look in his eyes hinted that he wouldn’t. When he grabbed my ass, it confirmed that.

I had on my favorite sneakers—a pair of green 5411s—and sped off as quickly as I could. To my surprise, he ran after me. My heart skipped. Touching me was alarming, but chasing me was terrifying. I tried to dodge him by darting into the corner store where I usually purchased my “nowlater” candies. I ran inside and just stood there catching my breath for a few seconds.

“You have to buy something or leave,” the man behind the counter yelled.

“I’m still looking,” I said.

I walked down an aisle of potato chips, glancing over my shoulder to see if he came in the store behind me. He didn’t. He stood outside looking at me through the front door. I walked to the back of the store and pretended to read labels of dog food. Despite not being a smoker I asked the cashier, “How much two ‘loosies’ cost?” I knew the cashier wouldn’t sell me the cigarettes, but I figured I could haggle with him for a few minutes.

“What are you buying?” the cashier asked in the frustrated tone he usually reserved for customers he suspected of stealing.

I wanted to scream, “I’m not stealing, I need help,” but I knew it wouldn’t matter to him. I knew he was about to kick me out, but I managed to stand in the store for about another ten minutes. Just when I was about to leave, I heard the sound of the police outside the store. I looked and saw a verbal exchange between a cop and the man who’d chased me. A crowd formed around them. The cop said something to the man. The man put his head down. There was a scuffle.

I heard an older woman yell, “Get ya hands off that boy, he just standing there about to go in the store, and you drove up and messed with him for nothing.” When the crowd thinned out, I saw the man being placed in the back of the police car. An older Black couple walked into the store. “Same cop always driving by, fucking with them same boys every day. Chasing them off the block. Putting their hands on them like it’s nothing,” the younger Black woman said.

“Always been like that, sister,” the older Black man said. The song describes the corners as our magic, our music, our politics. This is not the case for Black women and girls. For us, it’s a space where girls as young as twelve can experience sexual harassment and sexual violence and never mention it to anyone. I never told anyone the guys harassed me almost every day—not my mom or older brothers. Part of me thought it was my fault. I felt like I was doing something wrong to be harassed like that. I must have worn the wrong pants to make him grab my butt. Part of me was flattered by it—I thought I must be cute, and this is what men did when they thought you were pretty.

At twelve years old, I was bigger than most of the other kids, so I got more attention from twenty-year-old guys than I did from other preteen boys. Most of the time it made me wish I was invisible, except for when I thought the guy was attractive. In those cases, I would feel conflicted. I knew street harassment was gross and inappropriate, yet even though I lowered my head and walked faster, I would always find a way to work it into a conversation with my friend Mika whenever we were alone at school.

_______________________________________

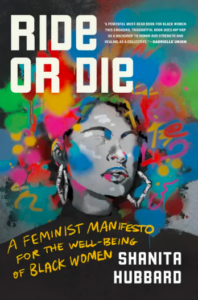

Excerpted from Ride or Die: A Feminist Manifesto for the Well-Being of Black Women. Copyright © 2022 by Shanita Hubbard. Reprinted with the permission of Legacy Lit.

Shanita Hubbard

Shanita Hubbard is an acclaimed writer, sociologist instructor, adjunct professor, Soros Fellow, and recipient of the James Baldwin writing residency. Her work has been published in the New York Times, Essence, the Huffington Post, The Guardian, Pitchfork, and many more. She was featured in the On the Record documentary and is a clinical consultant for therapist. Ride or Die is her first book. Her greatest accomplishment is being the mom of a dope Black girl.