The Transcendental Genius of George Balanchine’s Ballet

From Jennifer Homans's Baillie Gifford Prize Shortlisted Mr. B

This: the suffering, the grit and hardship of everyday life, never once appeared in Balanchine’s dances. It did not interest him—it was pedestrian, a degradation of the human body and spirit. Even the dead bodies in his ballets were set against a backdrop of eternity and had a sense of spirituality and redemption that elevated the body out of the ordinary—dead bodies, yes, but really dead souls. These were bodies purified and transfigured by the disciplined practices of ballet. And if loss was a theme in his dances, so were love and full-fleshed joy. He made many gorgeously costumed ballets that built to a crescendo with colorful kaleidoscope patterns of dancers synchronizing ever more complicated and demanding rhythms. These were fantastic entertainments that lifted audiences into the great good humor of being alive. He saw himself as a musician and theater man, a traveling ballet master, and he had worked in great opera houses and touring troupes, from the Russian czar’s Mariinsky Theater of his training and youth to the Paris Opera, Broadway, Hollywood, and his own New York City Ballet (NYCB), which he cofounded in 1948. He said he was a showman, and like the old commedia dell’arte performers, he reinvented himself many times. He seemed ageless. For his dancers, even at the end of his life, “Mr B.” was a god and they surrendered their own young lives for a chance to dance his glorious ballets.

He felt like a man with two bodies and he lived in them both simultaneously, with at times heartbreaking personal consequences.

There was some part of him that did not think of himself as mortal at all. “I am not a male….I am water and air and I am servant.” Or “I am a cloud in trousers,” he said, a phrase borrowed from a poem he had learned early in life by the Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. Some of the dancers who knew him best secretly called him “the breath,” another word for spirit, really. What this suggested, and it was a central theme of his life, was that he felt like a man with two bodies and he lived in them both simultaneously, with at times heartbreaking personal consequences. The first was the trousers—the earthly man delighted by sensual feelings and desires, who loved good food, fine wine, beautiful women. He devoted his life to dancing and everyone said that in rehearsals, even in his old age, he was more physically animated, expressive, and alive than any of his astonishingly athletic and youthful performers. The cloud or breath was something else, and he saw it as the source of his gift. It wasn’t mind, exactly. It was more a physical inwardness, and at moments he could appear strangely detached, almost androgynous or asexual, like an angel who knows everything but feels nothing. A “servant” bearing dances to the gods. An airy floating spirit, elusive at times, even to himself.

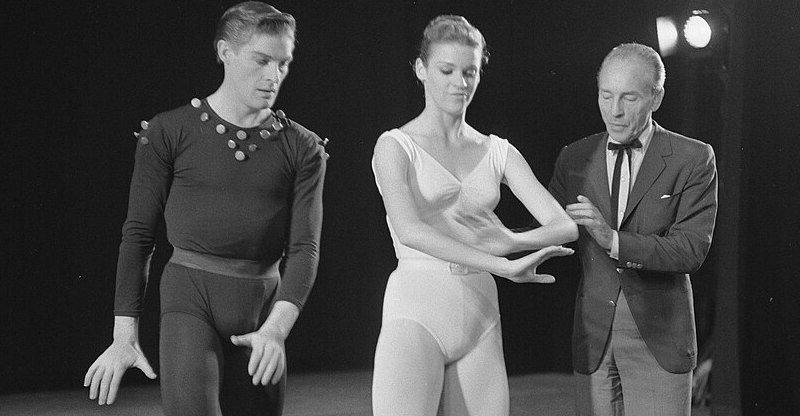

He lived through his dancers. He was not like Mozart or Einstein or Picasso, working alone to change the way people hear or think or see. He needed dancers and a whole theatrical enterprise, but dancers above all. His gift didn’t exist without them, and the most disoriented moments of his life were those when he found himself alone and unattached to dancers. He had to have them, and he gathered them and shaped them, making his own paints and pigments from their flesh and blood, meticulously reading and sculpting their minds and bodies. Making dances was personal, psychological, intimate even—they liked to say he knew them better than they knew themselves—and because women were his primary material, and because he was a man who loved women, sensuality and love were always a part of it.

For a genius, Balanchine felt small. “Maloross,” he called himself because he felt undersized, and as a child in Russia they had called him “the rat” for his persistent facial tic, a kind of nervous sniffing and twitching under the right eye as he spoke, almost like a visual stutter. He sketched himself in child-like drawings at the end of letters he wrote to lovers as a tiny mouse in the company of a large female cat that he fed and nurtured. In his mind’s eye, he was that man-mouse, “mighty mouse!”—a flourish at the bottom of the page, and he didn’t imagine himself as particularly attractive, though women found him sexy. The mouse was like the cloud or the breath—something a bit secret in their midst—a watcher scurrying around in his mind preparing great delicacies for his dancers and audiences to enjoy.

In reality, he was not small at all but physically quite average: average height, average weight, average proportions. He had fine, dark features—“I am Georgian,” he liked to say—and his Caucasian roots were visible in his dark, almond-shaped eyes, pensive and inward in portraits but lit and expressive in life. His forehead was high, and he had a delicate but large straightedge nose (“Bigger is better”) that became his signature feature in the sketches of his face in profile that he used to sign letters. Only his hands were fleshy and muscular, perhaps from playing the piano, which he did almost daily for most of his life. He liked to work with his hands—cooking, but also carpentry and gardening. He could be found at the local market carefully touching and testing for firm cucumbers or the perfect tomato. Smells mattered, and once he could afford it, perfumes were a routine purchase for the women dancers he admired (a different scent for each).

____________________________________

Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century by Jennifer Homans has been shortlisted for the 2023 Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction.

____________________________________

Appearances mattered too and he had a dandy’s interest in clothing and dress. Pictures from his St. Petersburg youth show him with a dramatic flair, hair slicked back in a Byronesque sweep with dark eye makeup to emphasize the point. Later, in Europe, he favored Italian suits and bow ties or colorful foulards, and he loved his American Western-style shirts with string ties and a turquoise flourish. In the studio it was a simple shirt, neat slacks, and flexible jazz or street shoes, and everyone remembers how he would roll up his sleeves as he entered the room, a sign that the work was about to begin. He took a personal interest in costume design and could be seen bent lovingly over a swath of fabric or absorbed in adjusting a headdress, and he always insisted on the finest materials for his dancers.

These sensual delights came against a backdrop of hardship and privation. He had experienced cold and starvation as a child in revolutionary Russia, his skin covered with pus-filled boils from malnutrition. The fear of gnawing hunger and the acrid smell of dead bodies piled in the streets in those early years never really left him. He had a weakened constitution. He was struck with tuberculosis (TB) as a young man, and soon after his arrival in the United States in 1933, he suffered mysterious epileptic-like fits and recurrences of TB, leaving him with a collapsed lung and narrowing left chest. Hardly a year passed when he was not suffering or seeking medical help for some real or imagined ailment—another source, perhaps, of his feeling small and vulnerable, but also part of his enormous stamina and determination to enjoy life’s pleasures and, above all, to make his dancers perform to their very fullest. “What’s the matter with now?” he would say. “You might be dead tomorrow!”

*

But really, it was all something of a secret. How Balanchine made his extraordinary dances and how the New York City Ballet had come to be—nobody quite knew and nobody could quite say. In the early 1960s, Balanchine wrote an unusually terse letter to his associate Betty Cage asking her to please turn down a request to write his biography by a journalist he didn’t particularly like. If he “wants to know about my inspiration, or who is my Muse,” Balanchine wrote, “then he will never know that. Because I won’t tell him, and it is not going to be written enywhere, for anybody to know.” There was something urgent in the secrecy, and Balanchine built walls around his gift and walls around his company, as if there were some kind of magic spell that might be broken by exposure. By the time he died, the company was not just a company; it was a kind of secret society, a utopian community with its own elaborate rituals and taboos, and they were all members, monks and angels, mute scribes and devotees of Balanchine’s art. Family secrets were never divulged, not because they were ugly or incriminating, though some were, but because the secret was part of the power, it was part of what they were all doing there together. If they knew, he once said, they would think I was crazy. Other than the dancers, Lincoln Kirstein—brilliant, huge, troubled, mad, loyal Lincoln— was the only one who understood, and they didn’t talk about it either.

Making dances was personal, psychological, intimate even—they liked to say he knew them better than they knew themselves.

Americans like to see Balanchine in their own twentieth-century light. Wasn’t he making ballet modern, abstract, twelve-tone, and progressive, and weren’t his dances icons of speed and urban accomplishment, ornaments to freedom and innovation? The State Department sent the company out on Cold War tours, and Balanchine went—“I am an American”—but the sight of Communism sickened him more than they could imagine. Russia was probably the deepest disappointment he had ever known. He had seen and suffered the way Communism could turn words and reason to wood, and he had set his own path away from the materialist Bolshevik Revolution that had violently interrupted his childhood and seduced his native land. And so there he was in New York City, quietly building a village of angels and erecting a music-filled monument to faith and unreason, to body and beauty. It was his own counterrevolutionary world of the spirit, an alternate vision of the twentieth century.

Balanchine himself was a kind of secret too. Restraint and civility were his natural disposition, and he was a deeply private man. The mask came naturally, at birth perhaps, but was fixed over years of history and experience. As he built the NYCB up around himself, he withdrew more and more inside. No drama, no tempers, no pretense, a simple craftsman at work daily. Even his use of language was secretive. He was a sophisticated linguist and spoke Russian, German, French, and English. He loved wordplay and puns and wrote limericks (many of them erotic) and romantic song lyrics. Yet although he lived in the United States for fifty years, he spoke a strange pidgin English that was extremely expressive but impossible to pin down in its winding syntax. It was brilliant but eccentric, hidden, foreign, part of the mask, and also a way of still being Russian—not Soviet but his own Russia, of his own making. He wasn’t an intellectual, W. H. Auden had rightly observed, but something more—“a man who understands everything.” “I have been alive for a long time,” Balanchine would later say, and he did know a lot, read a lot, but he held all of that to himself and dispensed it patiently in thin streams to reporters or dancers or curious outsiders who blankly ignored his digressions into the finer points of fairies or the afterlife. He conserved: energy, temper, ideas— concentrated them in an increasingly dense and secret inner world that had fewer and fewer outlets as he aged. By the end the only real problem he faced was the one he and his dancers had made together: how to live in the real world when the unreal world of the stage was so much more alive?

He didn’t think about it much. He focused on music, the grounding and “floor” of his life and dances. He read books. He played the piano. He absorbed. He cooked. He gardened. He liked carpentry. He ironed his own shirts and could be seen through the window of his apartment in the early morning hours with a towel around his waist, ironing alone. He washed cars. And he made ballets. The rest was left unspoken. It is all in the dances, he said. But it wasn’t, quite.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century by Jennifer Homans. Copyright © 2023. Available from Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Jennifer Homans

Jennifer Homans is the dance critic for The New Yorker. Her widely acclaimed, bestselling Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet was named one of the ten best books of the year by The New York Times Book Review. Trained in dance at George Balanchine’s School of American Ballet, Homans danced professionally with the Pacific Northwest Ballet. She earned her BA at Columbia University and her PhD in modern European history at New York University, where she is a Scholar in Residence and the Founding Director of the Center for Ballet and the Arts.