Did you gain a little weight? he asked, looking into my face. We were at the zoo on a Sunday afternoon, sitting on a wooden bench just in front of the giraffe enclosure, each trying to bite into an ice cream cone that was rock-hard from being left in the freezer box for at least half a year. Do I look like I did? I asked back. No, maybe that’s not it. Your face looks different from last week. Your chin looks rounder somehow . . . but that’s a good thing, he replied. Hmmm, I murmured, putting my teeth against the cliff-like surface of the ice cream, wondering what it meant that it was “a good thing” that my chin looked a bit rounder. Being round is good? Was it the same as liking? What did that have to do with my chin? Noticing my silence, he tried to change the subject and began to ramble about a pair of giraffes inside the fence. Why their necks were so long, where their color and patterns came from . . . little bits of information that seem amusing on the spot, but that you soon forget about. Did I say something wrong? he asked later with an apologetic look on his face, but by then I had already forgotten what he had said. You’re so quiet, I thought maybe you were angry, he said. No, it’s not like that . . . sorry. Both feeling awkward, we decided to skip the tropical birds and go home. See you in school tomorrow.

We waved goodbye. My head and temples ached.

When I came home and looked in the mirror, the shape of my face did seem changed somehow. There was an odd swelling below my cheeks. I held my face in my hands and wondered if I had the mumps. But could you get the mumps at seventeen? Wasn’t that for kids? What were the symptoms anyway? I had no fever, but I couldn’t shake off my headache and the pain around my temples.

During supper, my older sister sat across from me and stared into my face. Did your face get bigger? she asked. Mother and Father ate their chicken in silence. I, too, continued to chew on a piece of chicken in silence. Perhaps because of all the chewing, the pain slowly moved to my jaw and, by the time supper was finished, my entire face was hurting. I kept on chewing until I couldn’t bear it any longer, and as I got up to go to my room, I blurted out to no one in particular, My whole face hurts. Mother and Father remained silent. My sister laughed. That’s what happens to petty people . . . they’re scared and cowardly, but hate to lose and always try to look good. It makes their faces all tensed up. Isn’t that right? she said as she retreated to her room. Between the clanking of plates, I heard my father’s voice, so unfamiliar these days—Why don’t you go see the doctor tomorrow?

The pain in my face kept getting worse as the night grew deeper. Why didn’t I go see the doctor earlier? I regretted but climbed into bed telling myself that everything would be okay tomorrow. In the hazy darkness, the animals I saw during the day appeared one by one, then disappeared. They were all different types, but their bodies were covered in brown or white fur and seemed extremely heavy. How did I end up at the zoo? I didn’t want to go; I was asked to. Deep in the smell mixed with grass and manure and dirt, I could see the clear eyes of sheep and elephants, crouched in a hole-like place that was narrow and dark. I could have said no. I felt somewhat guilty for meeting a boy I didn’t particularly like on a weekend. It wasn’t fun. Even among friends, it was difficult to express myself when I wanted to say no, and using that as an excuse, I’d run away. Maybe I will always be like this, so ambivalent, and my eyes grew hot. But if I cried, some irreversible kind of fear might come crawling up from under the blanket, so I held my breath. Then, feeling something strange, I stuck my head out and looked over to the window. There she was as usual, beyond the glass—my sister, staring at me from between the curtains with her back to the night.

*

I woke up feeling short of breath. It must have been in the middle of the night, since the sky was still dark with not the faintest sound of morning approaching. Putting my hand to my face, I felt it bounce off something large and elastic that seemed to be coming out of my mouth. It was a tongue. The tongue grew bigger and bigger until it no longer fit inside my mouth, and when I looked down, I saw the tongue curled up on top of my chest. So that explains the pain, I thought to myself—the tongue was trying to escape.

The tongue overflowed like fluffy foam, without pause, and soon it was as big as my body. It got bigger and bigger until it spilled over the edge of the bed and slithered across the floor. There was no longer any pain in my mouth or chin or face or head, and as I turned over, the left side of my body landed on the soft tongue. It was a sensation I had never known before, different from any bed or grass or earth that I had lain down on. As I looked on, I noticed something that resembled a meadow unfolding before me. I climbed down into it and looked up at the blue sky that opened in an oval shape. At my feet were the animals I had seen during the day. With nothing to constrain them, they seemed lost, not knowing how to behave in their newly obtained freedom. As I walked in the direction that smelled like south, a warm, giant wind blew again and again and shadows ran and cut across the grass. I could see, among a herd of mountain goats, Father and Mother seated across from each other and eating chicken at their usual dining table. They were in tears as they chewed the chicken. Hey, you don’t have to keep eating, I wanted to tell them, but because of the condition my tongue was in, I could not utter a sound. The chicken grew cold on their plates, and Father and Mother kept moving their icy fingers as they chewed in tears. It’s always like this, I can never speak up when it’s really important, all I can do is watch. It makes me sad, it makes me want to do something. That’s not a lie. So how come I always pretend like nothing is wrong? Why do I forget so quickly?

With the banging of the door, the meadow shook and low dark clouds quickly covered the sky. My sister is here, I thought. Or was it the boy I went to the zoo with today, the boy I barely know? Perhaps they are standing there together. The banging of the door didn’t stop, it only got louder. Hearing a sound of wind I’d never heard before, I looked up to see a giant rock floating in the sky. The sound became more and more unbearable. The rock will come crashing down soon, I thought. It will crush the animals on the grass and the dining table of Father and Mother, and create a hole in the exact shape of itself. And so before they arrived—my sister, the boy—I rolled up my tongue using all my strength, and swallowed up all there was that lay before me.

__________________________________

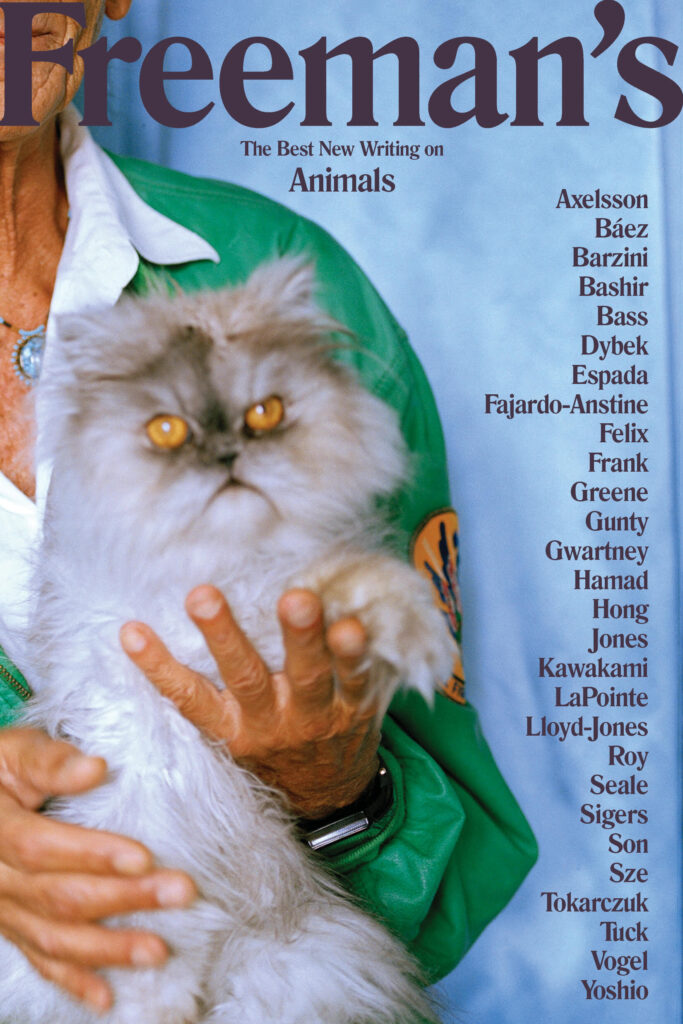

From “The Tongue” by Mieko Kawakami (translated by Hitomi Yoshio). Used with permission from Freeman’s. Copyright © 2023