The Time I Stole Tama Janowitz’s Slaves of New York and Couldn’t Stop Reading It

Elwin Cotman on His Frustration and Enchantment with a True 1980s Classic

Exploring the discount bin outside Dog Eared Books, I discover Slaves of New York by Tama Janowitz, which is not, I learn, a historical text about the slave market on Wall Street. The cover features a man and woman photographed like Warhol silkscreens. On the back, Warhol himself calls the stories inside GREAT! SIZZLING! WOW!

It’s 2008. Though a San Francisco resident, I crave “Girl in New York” stories. Felicity Porter, Lena Dunham, Eileen Myles—in books and TV shows, I’ve watched them come of age in their frothy version of Brooklyn. As a black man, I have to tell myself this fascination isn’t me idolizing whiteness. No, this must be, like Venus Xtravanganza before me, a rational envy for those society deems valuable. A desire to chase my dreams through a maze of hangovers and strange lovers and suffer mere embarrassment for my mistakes. It seems I’ve found another such fantasy in this Reagan-era relic about itinerant artists—provided I steal it. Bohemian behavior for a bohemian book. So, Slaves in hand, I keep walking.

The more I read Janowitz, I’m convinced that laughter is the only way certain stories can be told.I read seven or eight stories before putting it away. Too much of the book focuses on Marley Mantello, Janowitz’s comic fool, an artist starved for food and talent whose fumbling quest for patronage seems to amuse the author greatly, myself less so. And for stories about 1980s New York—that era when the city fountained with underground culture, when geniuses like Basquiat flew on spray-painted wings from the train yard to the penthouse to tell their patrons, “Unto you realness is born”—the fact that Janowitz writes about untalented artists doesn’t compel to finish what are, for the most part, longer short stories.

It’s also possible that she writes her elitist gentrifiers too well for a left-wing youth such as myself. I groan at the title story when Eleanor, a jewelry maker living with an emotionally abusive boyfriend, calls herself a “slave.” In Janowitzland, artists in toxic relationships are the slaves of New York, and this is, prior to another writer calling slavery a choice, the most obtuse line I’ve read on the subject. That’s not to say the book is poorly written. Over the years, I’ll borrow Slaves from the library many times to reread “Engagements,” one of my favorite stories.

*

In 2022, I’m living in Oakland. Despite having two books on contract, I am too stressed to write. As the midterms approach, white supremacists are disenfranchising my people, and I feel powerless against the coming bloodshed. America is falling—the question is, will the weight of its collapse land on me?

Like James Baldwin, I flee to France for peace of mind. There, store owners at Chatelet stalk me while I try to shop. Seeing as I’m clearly a tourist, I want to ask them, “Do you think I shoplifted the plane ticket to get here?”

The Brits in the cafés laugh when I say America is headed toward fascism. Leaned back, one leg crossed over the other, they wonder why Americans are obsessed with politics. My fellow countrymen say France is three elections away from another Vichy. Nevertheless, they agree that living in the States felt like slow death, and they do, in fact, consider themselves better than those people who’d vote for a dictatorial gameshow host. Most are pursuing French citizenship, determined to scrub themselves of red, white, and blue in a country where the average person wears those colors on their cheeks. The nightly soccer games nearly cure my alcoholism—the moment I glimpse a bar window fogged in sweat, I go elsewhere.

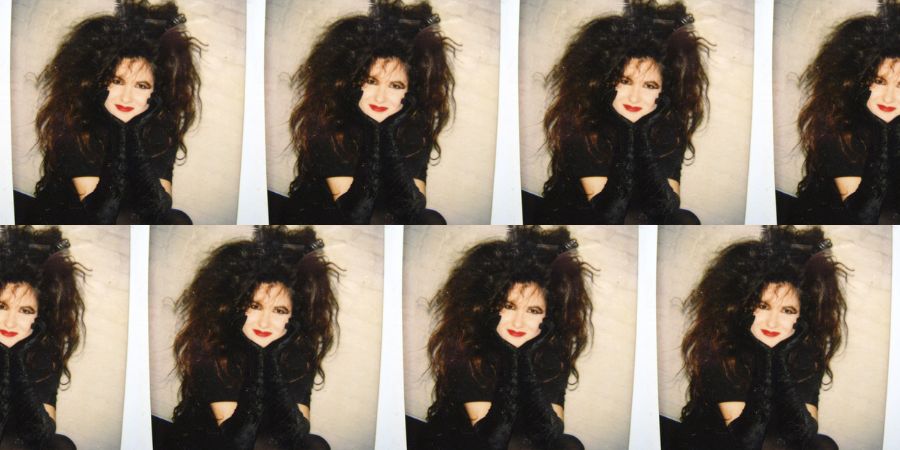

Besides my contracted work, I’m writing a novel set in 80s NYC. This means reading everything I can find about the period. Leaving my hotel on the Boulevard Saint-Michel, I walk cobblestone alleys to the closest anglophone bookstore. Built into the old Hotel Dubuisson, the place feels like a catacomb, the aisles between high shelves wide enough for one patron at a time. There I find a promotional tie-in for the awful 1989 Slaves of New York film adaptation, featuring Bernadette Peters and Adam Howard as Eleanor and Stash. Both actors look cramped and doleful on a cover stamped with a PRINTED IN CANADA maple leaf in the top left corner. No sooner do I depart with it—purchased this time—a piece of the cover snaps off. (As far as I know, Slaves has never had a good cover, either aesthetically or structurally.)

Sometimes, I can snag one of the half dozen tables inside the Shakespeare and Company Café. Outside, bloated gray clouds hang low over the metal cage around Notre Dame.

“I don’t know what my greatest fear is,” I read Eleanor muse, as she watches artists play a midnight softball game, “maybe that I’ll be caught and discovered, accused of being a child in an adult’s body.” In that same story, she finds herself competing with an actual child over who’ll play catcher. Her boredom leads to dreaming. “Below the bridge is an alcove, hidden from the cars but visible to pedestrians. If things don’t work out with Stash, maybe I’ll take my stuff and live in that little hole.”

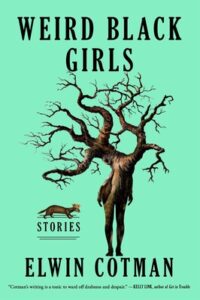

Over the following days, I read more such flights of fancy; Janowitz’s deadpan insights and creative similes keep her stories crackling from anxious beginning to ambiguous end. Even the Marley Mantello parts keep my attention through their sheer linguistic dynamism. Among Sorbonne students in the Saint-Michel Starbucks, I revise my book Weird Black Girls while reading Slaves, feeling my own writing start to dance.

At the laundromat, I read Janowitz’s nonfiction. Her essays about the 80s come across mean-spirited. Having spent her youth in the SoHo scene, she views her peers as clout-chasing drug addicts, one big circle jerk around mediocre art. What keeps Slaves from similar hipper-than-thou sneering is that Eleanor, the protagonist in eight stories, is not above it all. She craves this discount Neverland; she suffers pain and humiliation for it; however, in the end, she simply lacks the energy to pretend any of it matters.

This is new to me—a bildungsroman about an ordinary person. A mopey, uncool, conservative person whose detached observations provide the perfect window to this world.

*

In early January, my estranged sister contacts me on social media to inform me that our father had a stroke; from that point, our shared trauma manifests in no time, as if we still dwell in that house where our mother pitted us against each other. She refuses to tell me the hospital where Dad is staying. So, on a transatlantic flight to New York, I find myself mentally in tune with Eleanor’s rage at the cycles she finds herself in.

With the perfect language, the perfect tone, and the perfect sequencing of stories Janowitz crafts a tale that is funny, empathic, and wise.“If I had gotten into the limousine earlier that evening,” she muses after turning down a chance to party, “I’d be in the same mess, only in a different neighborhood.”

Hours after landing in LaGuardia, in a Brooklyn café, I’m incrementally sipping a $14 chardonnay, elongating my time on their wifi, my suitcase beside the table, tracking down Dad’s remaining siblings to ask them which hospital he’s in, while, at the same time, uploading course materials for a Zoom class I’ll be teaching soon. It is on the bus to Richmond when it occurs to me I could’ve asked for a deadline extension.

*

Over the next couple of months, I rent a string of desolate Oakland Airbnbs where, in between remote work, I continue reading Slaves from beginning to end; soon after starting my Zoom class, the stereo short-circuits on my old MacBook; during the final week of class, the organization I’m working for cancels further workshops, leaving me jobless; right as I’m releasing my poetry debut, the publisher folds.

In the future these will be funny stories. Someone famously said we laugh to keep from crying, but the more I read Janowitz, I’m convinced that laughter is the only way certain stories can be told, period. Her drollery speaks to the truth that pain itself isn’t inherently profound. That some people in this world really are shallow and boring, and you either make a joke of them, or you say nothing.

One day I’m reading at Lake Merritt, on the knoll across the water from the Vagina Church, as we call the cathedral with a vulva-shaped atrium. I’ve left petals of cheap cardboard across the planet; my copy of Slaves barely has a cover anymore. In “Fondue,” Eleanor reflects on the adventures she had while studying abroad in England. In my experience flashbacks, even when done well, function as awkward exposition. Janowitz freshens the formula by writing flashback as memory—the realtime action of Eleanor reflecting on her life. Recalling the interesting things she’s done prepares her for when Stash dumps her.

*

Early April and I’m on book tour in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, the definition of a sleepy college town where the sun hits the rooftops just right for that wistful, golden feel. It’s the birthplace of Keith Haring. (Someone Janowitz knew personally. She hated him.) I’m staying in a bungalow belonging to a friend’s parents. Afternoon walks. Home-cooked meals every night. I do a reading at a local bookstore where my mother shows up unannounced. I ask her to leave.

Then comes a dusk where, sitting at the rolltop desk in the guest room, I finish Slaves. Eleanor, having moved on from Stash, remains inept at dating. To celebrate her newfound liberation she throws a party that only serves to reaffirm her introversion, and Janowitz closes on Eleanor choosing to hate the situation rather than herself. Unlike the typical coming-of-age where the protagonist levels up, Eleanor learns self-acceptance. It’s a powerful message.

The final story, about the sadomasochistic relationship between an artist and his muse, is grim enough for a Mary Gaitskill book. As if Janowitz, having thrown every pie in her arsenal at the art scene, is finally prepared to stare on the darkness, right as she closes the book on that chapter of her life. It’s unclear to me whether the lessons she learned in her twenties apply to me as I near forty. I’ll never be a white woman, never know their sense of safety. But I admire this book. With the perfect language, the perfect tone, and the perfect sequencing of stories Janowitz crafts a tale that is funny, empathic, and wise.

Done with the book, I have a hard time looking at my bedraggled copy, and my luggage is heavy. I leave Slaves in a Little Free Library in Kutztown. I board a bus to New York City for my next reading. One hundred miles away.

__________________________________

Weird Black Girls: Stories by Elwin Cotman is available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon and Schuster.