The Time I Met New York's Patron Saint of Typewriters

Stanley Adelman, Savior to Philip Roth, David Mamet and More

One hot summer’s day I brought my broken typewriter to Osner’s Typewriter Repair on Amsterdam Avenue and 79th Street. I was in a state of panic because my boyfriend had walked out a week ago. I was a student, earning a pittance as a copyeditor, and the landlady had already asked how I’d pay for more than half the rent. My mind skittered with random thoughts. Sleep, when it came, had dreams about the breakup that scraped my heart. But during the day my grief was buried under terror about survival.

New York was in its eternal process of reconstruction and demolition. A third of the sidewalks were torn up, cranes were devouring buildings, and drilling rattled the sidewalks. The heat was so intense that even the subway shimmered. I carried my typewriter up to the street like a stolen offering from Hades.

Osner’s Typewriter Repair was pungent with ink. As if the walls had given birth to them, typewriters were everywhere. The owner, Stanley Adelman, was a wiry man with a hawklike face. He took a moment to look at the typewriter and began to tell me the problem in great detail. He showed me gears, wheels, lock-release levers, and lift-frame springs: a mysterious world of silver metal and black spools.

On that particular day I couldn’t have followed a recipe. But since I never bothered to understand anything mechanical, I’d long made pretending to understand into an art. While my mind continued to race, I nodded in a display of intelligent comprehension. This never failed, because the expert who happened to be explaining never stopped talking.

But Stanley Adelman saw that I didn’t understand. His intense blue eyes telegraphed the urgent message that he wouldn’t settle for anything less than my knowing as much about my typewriter as he did. He repeated himself and I nodded.

He repeated himself again.

The more I nodded, the more he repeated himself. I began to feel the way I felt in high school detention when I only wanted to leave. But it was impossible to leave—or even space out: Stanley Adelman never took his eyes off me. I sensed he knew I couldn’t listen because I was in a state of panic. Yet he kept addressing the rational being that lived somewhere inside it.

After the fourth or fifth explanation something unprecedented happened: my chaotic thoughts disappeared. Each gear, wheel, and lock spring became lucid. I understood.

I didn’t say anything to let him know—the interaction was between our eyes. I met them and felt a startling clarity, an arc of light. When he saw I understood what he was saying, he told me the typewriter would be ready in three days.

*

Stanley Adelman had powerful arms. His shirtsleeves were rolled up and, from the periphery of my vision, I saw blue numbers on his arm. I’d seen photographs of these numbers in articles about the Holocaust, but confronting them on a survivor made them seem defiant, even triumphant. For a moment I imagined clandestine meetings over fences in the camps, in ghettoes before curfew, or in underground sewers. People met in such places to give and receive messages that were crucial to their survival. Many of them were flooded with terror and in no condition to understand. Yet it was in just these circumstances that one needed absolute and mutual comprehension.

By the time I left Osner’s Typewriter Repair I felt as though I’d emerged from a dark passage into light. I still didn’t know how I’d pay the rent. But the random thoughts disappeared and I no longer felt the cacophony of New York inside of me. As I walked back to the subway I was cradled by a tangible sense of peace.

Over time, in the way New Yorkers grow intimate by sharing fragments of their lives, Stanley Adelman and I became friends. At first I visited only when my typewriter needed fixing. Eventually I’d stop by the store. There were often other people there—all of them older, all of them male. Stanley always introduced me by saying, “This is the writer, Thaisa Frank.” He said it matter-of-factly, not opening it to question. Then he’d turn his attention to me.

“What have you been working on?”

“A story.”

“But what story?”

I was always vague about my work. He teased me by telling me he’d seen some good movies but couldn’t remember their names. Our conversations always focused on details: the pristine velvet couch that had been on the corner of 78th Street for weeks, the five perfectly matched terriers that walked by every day on a leash. I felt I had a fellow traveler in the way I saw the world.

*

Twenty years later I was living in California and had published a few books. One day, in the New York Times, I read “Stanley Adelman, Repairer of Literary World’s Typewriters, Dies.” He’d never told me that David Mamet, Alfred Kazin, Erich Maria Remarque, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and Philip Roth brought him their machines. Nor did he tell me that David Handler wrote him into a novel, using his real name and casting him as a magician of typewriters. According to the Times, Stanley Adelman spoke Polish, German, Russian, and Yiddish, and could figure out typewriters in languages he didn’t understand—Arabic, for instance—solely from keyboard diagrams.

Howard Fast told the Times that Stanley Adelman kept his Underwood alive for more than 40 years. When the typewriter was so old he couldn’t find parts, he suggested an Olympia. Howard Fast, who was Jewish, said he couldn’t write on a German typewriter.

“I was in a concentration camp,” said Stanley Adelman. “If I can sell that typewriter, you can write on it.”

Howard Fast bought the Olympia.

*

The six blue numbers on Stanley’s arm telegraphed parameters that had defined his life in his early twenties. He had been to four other camps by the time he arrived in Auschwitz late in the war. This was when Auschwitz began to tattoo prisoners’ arms instead of stamping their clothes.

I imagined his conversation with Howard Fast being like our conversation that summer’s day: Howard Fast not listening. Stanley Adelman talking until he got through. I wasn’t the first impenetrable wall.

Before I read the obituary I’d had a vague idea for a novel about World War II. It included a title and two indistinct characters. As soon as I read the obituary, I realized one of the characters had always been Stanley Adelman.

Turning away from terror is as instinctual as turning away from a wound or jumping back from fire. But Stanley Adelman turned toward it and met my fear. I don’t know if this came from his particular experiences in World War II, but I do know that the long moment when he held me with his eyes changed my ability to cope with panic forever. Not being alone with terror left me with a sense of courage about facing suffering and terror in other people. It taught me not to turn away.

When I read the obituary I remembered the meeting between our eyes—the sense of shock and clarity. This became a lens when I began to read about the Second World War. I could hold the atrocities against a backdrop of lucidity, and this allowed me to create a narrative.

Given the writers who trusted him, I’m sure Stanley Adelman listened to many voices with patience and compassion. I imagine he used these same qualities when he worked on typewriters, asking gears to mesh, lock springs to spring, and obstinate keys to unstick. He spoke to them patiently, the way he spoke to me that hot summer’s day. He settled for nothing less than compassion and lucid understanding.

__________________________________

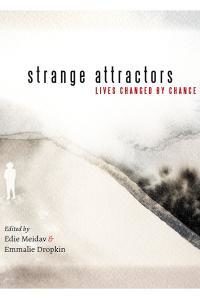

Excerpted from Thaisa Frank’s “Stanley Adelman: Magician of Typewriters,” forthcoming in Strange Attractors: Lives Changed by Chance, published March 2019 by the University of Massachusetts Press.

Thaisa Frank

Thaisa Frank’s fifth book of fiction, Enchantment (Counterpoint, 2012) was selected as a San Francisco Chronicle Best Book of the Year and her novel, Heidegger's Glasses (Counterpoint 2011), was translated into 10 languages. Recent work has appeared in New Micro (Norton) and Short-Forms (Bloomsbury). She lives in Oakland, California and is a member of The Writers Grotto.