The Terrifying Doubts—and Important Lessons—of Becoming an Older Father

Josh Mohr Reckons With a Later-in-Life-Changing Event

Ava was born in the morning, and by the time eight o’clock rolled around that night, Lelo was out cold, exhausted from the difficulties of childbirth. Ava was awake. I was awake. I sat in a rickety chair, next to Lelo’s hospital bed, and read my daughter Franny and Zooey. I only expected to read her the first few pages, but she was content. I finished thirty while she cooed and kicked on my lap. I read the next fifty after doing my first solo diaper change, a humbling experience. I woke Lelo for a quick breastfeed, and after a burp, Ava and I returned to our lumpy chair—the place where I was supposed to “sleep”—and picked the book up where we left off. Ava dozed on my chest, and I kept reading aloud and finished the thing, sharing one of my favorite novels on her first day here.

A couple weeks after her birth, my mom and I decided to give Lelo a break—take a shower, take a nap, take a breath—so we bundled Ava up and put her in the stroller.

I was freaking out, wondering why I’d voluntarily ruined my life. What would happen if I dropped Ava off at the fire station’s Safe Surrender site? How angry would Lelo be?

That’s the thing about being an older dad: you’ve engineered a day-to-day life that you dig, deriving pleasure from the narcissism of your routine. Since 2009, I had published four novels, writing every day and earning a living teaching other misguided romantics to churn out pages. I worked out; I traveled around doing readings; I spent time with Lelo, my best friend and favorite author.

I pushed the stroller, Mom walking next to me.

“I keep crying,” I said to her.

“That happens.”

“I’ve made up these little lullabies for her and I can’t get through one without crying.”

“It makes sense.”

“How do you figure?”

“You’re in a new style of love,” she said. “One you’ve never known before.”

“As long as you’re not stupid,” she said, “everything will be fine.”

We were up at Holly Park on Bernal Heights. It’s a small, circular park that has a concrete walkway running around the outside of it and we pushed the stroller in this circle, doing laps.

“It’s harder than I thought it would be,” I said. “Being a parent?” she said.

“I might not be able to do it.”

“You’re already doing it.”

“That’s not what I mean.”

“It will get easier,” my mom said, “and it will get harder.” “Super.”

“Josh, she’ll never know you the way you knew me,” she said, stopping.

I stopped too, the stroller fixed in front of me.

“She’ll only know you sober,” she said. “Do you know how fortunate that makes you?”

“Who knows if I’ll stay sober?” I said.

“Don’t you dare.”

“You know what I mean.”

“Only sober: I wish that was how you knew me. Can you imagine?”

I didn’t want to construct some fiction about our past, didn’t want to worry about what had already happened. I wanted to stop circling the carcasses of all those years, which was one of the reasons I loved drugs in the first place: they yanked me into a paradise nude of memory. And it worked. Drugs helped me for years. That’s what nobody tells you. Drugs help until they don’t. But by then, you can’t stop.

Nothing is my mom’s fault. Sure, there’s some genetic junk floating in me, unseen but dangerously there, like plastic in the ocean. But I ate that acid, smoked that heroin, shot that Special K, bought those bindles.

My mom and I were still stopped in the park. A jogger whizzed by.

She had waited ten seconds for me to answer, and when she realized I wasn’t going to say anything, she added, “Look at the baby,” putting her hand on the stroller, right next to mine. “Just look at her.”

Ava slept, my three-week-old miracle, my three-week-old mindfuck.

“She’ll only know you sober,” my mom said. “Just don’t be stupid.”

“Okay.”

“As long as you’re not stupid,” she said, “everything will be fine.”

__________________________________

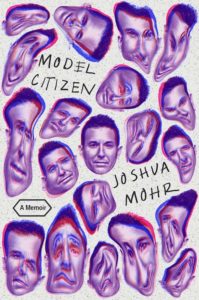

From Model Citizen by Joshua Mohr. Used with the permission of MCD. Copyright © 2021 by Joshua Mohr.

Joshua Mohr

Joshua Mohr is the author of five novels, including his latest, All This Life, recently published by Counterpoint/Soft Skull. He lives in San Francisco and teaches in the MFA program at the University of San Francisco.