A few weeks before my wedding, one of my friends told me, in the presence of my future husband: “I had a dream that you dumped Doug, and he was hitchhiking on the side of the road, all sad and lonely, with his thumb out, and you drove by in a fancy car and didn’t stop to pick him up, and he was crying and running after you down the road, for miles and miles and miles, begging you to stop the car and take him in, but you just kept driving.” She paused there. “In fact, you accelerated.”

This was years before the term microaggression was coined, but later on, when it became popular, and “Conversational Don’ts” started to come across my social media feed, such as “Telling a person you are surprised to see them in such-and-such a setting,” I would always mentally add, Relating a possibly fake dream to a person in which the person figures unflatteringly.

Before I met Doug, I had composed a list of requirements in a spouse. It wasn’t a mental list—I had jotted it down on a Post-it that I came across periodically, marking, e.g., a passage in The Seven Habits of Highly Successful People or clinging to an interior zip pocket of a faux-leopard clutch (I am not sure the fashion writers can justifiably claim that animal prints are ever “back,” given that they never truly seem to go away). Nice manners was the sine qua non my eyes alit on most frequently because it was near the top of the Post-it—second only to job. By job, I meant something you put on a suit for—it was the ’90s, and I wasn’t having any of this tech-world no-tie nonsense.

In my early twenties, I had a fling with a guy who was getting an MFA in film studies and wanted me to shop with him for mock-turtleneck sweaters. “Shop with you?” I remember I asked him after a long pregnant pause. The subject of mock-necks swiftly died.

Going Dutch? No.

Sharing breakthroughs you’d had with your shrink? Goodness, no.

My nickname in college was “Picky,” and in the group house I lived in, my then boyfriend used to have to come over when it was my night to cook. His specialties were fettuccine Alfredo and a beef and broccoli stir-fry. I toyed with dumping him senior spring, but I needed access to a car.

Cut to a year into my marriage.

Doug is gone at the finance job eighty hours a week. Jobless myself, I wanted at least to pick up his shirts for him, but whenever I went into the dry cleaner’s, ticket in hand, and announced, “I believe you have some shirts for me!” the proprietor would remind me testily that they offered free delivery. From the man’s passive-aggressive insistence on this point, I gathered that performing this service gratis truly mattered to him, so in the end I let it go. (Not to let him seize the upper hand entirely, I insisted on light starch and eschewed plastic and hangers in favor of the boxed option for shirts, despite the impression I had that the latter was not a true option but was there only to pad out the price list, as boxed or hung!—yes, there was an exclamation point on the sign—sounded so much more exciting in a choose-your-own-adventure sort of way than simply shirts: laundered.)

I am talking about the time before Marcus came, of course.

After Marcus, everything changed.

Before my friend Gillian sent Marcus to stay with us, I spent my time googling rescue dogs and obsessing over having bought the wrong couch. You think of blue as the most basic of colors, but it turns out to be tricky—it turns out to be cold. I also made a point of reorganizing the apartment a good deal in order to attain maximum efficiency in Doug’s and my homelife: our closet; the spice cabinet; the books, though never by color—that, to me, is misguided. Sitting in the nail salon one afternoon—I stuck to a regimen of regular manicures and pedicures even if there were other things I felt like doing on manicure day—I read an article that said that busy couples should schedule sex, and while I could not claim to be busy in any broad sense of the word, an eighty-hour-a-week job in a Midtown investment firm certainly qualified Doug. I let him know that Fridays and Tuesdays would be our nights, with a free option for Saturday afternoon. Occasionally, when I reminded him about the Schedule, say, or noted that the spices were now alphabetized, with the exception of the star anise, which was too large to fit in its rightful place, between sage and tarragon, I caught Doug looking at me sideways, a bit like you look at someone who is making a scene in a waiting room, someone whom you might actually sympathize with if you were alone but vis-à-vis whom, since people are watching, you need to draw a line. Also, if I went out and left him alone in the apartment—a rare occasion, given how much he worked—when I returned, I would often find him playing such popular heavy-metal bands as Metallica, Black Sabbath, and Iron Maiden while slamming a fist into a long round pillow known as a yoga “bolster.”

I have often asked myself in retrospect why I felt compelled to accept Marcus DiDomenico as a houseguest. On the isle of Manhattan, as everyone knows, it is an effort to let someone spend a single night in one’s apartment, let alone an astonishing, unprecedented string of eleven. Doug and I were, as I said, newly married. We were living in a one-bedroom-plus-alcove that our broker had assured us could work as a nursery just as soon as we felt “the urge to expand,” which, I took it, did not refer to the weight gain we newlyweds were likely facing as we started down the path toward middle age. In these intimate quarters, I didn’t have room for anything but a close friend— Gillian herself, say, not her ex-boyfriend, this Marcus fellow whom I had never met. Which was not to say that he wouldn’t be perfectly pleasant. But more to the point, I didn’t have the psychological bandwidth to share my physical space. Everyone who had ever known me knew this and kept their distance. In college, I lived in a single. Afterward, I was never asked for a room or a bed. I was never asked for much of anything, though I spent long hours in our new apartment considering how I would make hypothetical guests comfortable and had already worked out exactly the traffic pattern that would be most commodious for everyone: I would shower at night; Doug would shower early; the guest would have coffee in his or her robe and then shower.

It must have come down to flattery.

Among my friends from college and from the early years in New York, there were those who had a nonstop stream of houseguests. I would ask them what they were doing of a weekend ( just casually making conversation) and be told that Ronnie or John or Kimba Lee Downing or Beth G. or the Hanlons, after they spent a night in a Boulder, Colorado, jail, or Greta Weicker’s sister, who was auditioning for the touring company of Rent—someone—was always in town, crashing for a few days. These friends were not better off than I, with more to offer in the way of accommodations. It was I, in fact, who had escaped the dreary, almost incapacitating penury of our twenties by marrying Doug. These friends lumped it with their guests—sharing bathrooms, of course, and beds, leaving keys with supers, making the guests take care of their rescue cats, car-walk their cars, even come down on weekends from “upstate” or “Mass.” or “Syracuse” expressly to help them move apartments. We all moved constantly in those years, and two things these “friends” of mine always had besides houseguests (I am never sure with this particular group of peers whether to put that word in quotations or not) were rescue cats and people to help them move. No one had ever showed up to help me move. I had ridden in the cabs of trucks with crews of Israelis I’d hired on glib recommendations; in my more budget-oriented moments, I’d ripped tabs off Man-with-a-Van signs on telephone poles and, once, a Woman-with-a-Van sign; that mover turned out to be somewhat of a liability as she couldn’t lift my flea-market urn turned planter, and I had to call in reinforcements, namely, a Man-with-a-Van. I’d been alone—metaphorically speaking—when the brassieres I stuffed into the box of cutlery because they were air-drying when the movers arrived fell out on the street and into the gutter. Still, I had a history with these friends, and I kept up with them in my fashion. I had invited them to my wedding, for instance. Doug and I got married young—the cutoff IMO was thirty— with bridesmaids and engraved invitations, not embossed, and I remembered eternally and with perfect clarity who came but never sent a present. Of course it was this very same group of friends with the rescue cats who couldn’t be bothered to ask where Doug and I were registered, who found the idea of registering comical, found weddings comical, found the words bride, groom, mother of the bride, canapés, and receiving line all comical. When some of these friends eventually did marry, at the tail end of their thirties, the ceremony was in a field somewhere, and despite our twenty-year history, I was never invited.

Gillian Dunn was outside of this circle of mostly college

friends and acquaintances. She and I had met at a party on the Lower East Side and hit it off. I’ll just admit up front that it was our fault Pataki got elected. We were drinking in a room with the TV on when the election results came in, blaming “low voter turnout” for Mario Cuomo’s loss. We looked at each other, cleared our throats, and moved away from the television into another room. Later—unrelated to the New York governor’s race—Gillian moved to Paris. A few months after that, she e-mailed me with the name of an old boyfriend— American, she hastened to clarify, in case I thought I’d have to entertain un gentilhomme français—who was moving back and needed a place to crash for a few days. Of course!! I wrote back, after waiting half an hour to give the impression I was thinking it over, though in fact I had already rushed ahead to ordering sheets from the Company Store for the foldout love seat— overnighting them in case the friend’s dates changed.

I wrote, Of course!! and added breezily, Let me know when he’s showing up! and then, No, it’s totally fine with Doug! He won’t care at all!

In fact, I wondered briefly if my husband would care— if indeed he would be put out by having a guest in the one-bedroom-plus-alcove when he returned from his exhausting, exacting job and by having a stranger walking through our marital sanctum/bedroom to get to the foldout in said alcove. My response to these doubts was to delay telling him until two nights before and then spring it on him as a fait accompli.

And so, a few weeks later, on a gray and drizzling early-spring afternoon, I was buzzing up the first nonfamily houseguest of my married life.

In a stroke of bad luck, it was the cleaning woman’s week off, so I had done a surface cleaning of the entire apartment. I’d also laid in a supply of groceries—coffee, fruit, individual yogurts, and things I am told people like, such as prepared salsa and the ubiquitous hummus and “guac.” The night before, now that Doug knew about our guest, he had obligingly hung up eight pictures under my direction. They had been sitting on the floor, leaning against our bedroom wall since we moved in. Eager to help, I threw myself into the task, letting Doug know when a print was not straight despite what he thought, saying, “Don’t you want to use a level? I’m sure it would be better!,” having him raise them one inch, lower them two, align them with the molding of the doorway, then align them purposely not with the molding of the doorway as I tried to recall whether there was a rule about this. I mused aloud, but only briefly, about whether prints were even really what we ought to hang on our walls at all. At some point I heard Doug saying under his breath that he had to go to bed or he wouldn’t be able to work in the morning at the job that paid for our lives, and I said, a little tearily, “Okay—jeez! I’m just trying to make the apartment look nice for our guest!”

Other than the decorative question of prints, only one thing frightened me in the minutes before I opened the door to Marcus—it had been worrying me all week. In the few months that Gillian had been living in Paris, she had gone completely French. That was one of the reasons she felt so confident moving over there—she knew she had it in her to go French and she had done it, seamlessly, from what I could tell. The language, yes, but also the driving, the parking, the fashion, and the cooking were immaterial to her. She learned all of the idioms as if she’d spent her whole life, instead of about a month and a half, stuffing trash into tiny cans and eating with her fork turned down. Guessing at the life Marcus had led with Gillian, at what my future guest was accustomed to, instead of suggesting that Marcus and I order a pizza (Doug was working late, as usual), I had run out as in the old, single days and done the equivalent of buying a fluted tart pan and four new spices. (I still owned the actual fluted tart pan from years—and many, though exceedingly intermittent, tarts—ago.) Finding it difficult to focus on, I rarely cooked for the two of us. I had spent either a week or three and a half hours—depending on whether you count time spent in big-picture contemplation or time crunching actual recipes—deciding what to cook for this, our inaugural guest-dinner. I had rejected fish as too tricky and pasta as a cop-out, meat as too stagy and sycophantic, and vegetarian as too Moosewood/rescue-cat. For a long while, I stared at the suggestion for “An Academy Award Buffet” in the Silver Palate Cookbook. But in the end, I was left with chicken. Surprisingly, I had always been able to make a decent roast chicken; my college boyfriend showed me how when my housemates did a faux Thanksgiving our senior year. I copied Dean’s instructions exactly, down to the type of pan he made it in, a glass Pyrex baker; I would not have known what to do with a ceramic or metal one. I made it with lemon and tarragon on a bed of onions and celery, and I cooked it on high heat till it was past done. I had the very index card I’d written the recipe down on in college and I always read and repeated Dean’s ingenious insight as I cooked it: “People like overcooked fowl”; it was a kind of calming mantra. This was the only dish you could say was part of my repertoire—let’s face it, it was my repertoire. So, after much, in retrospect needless, contemplation, I decided to make the chicken for Marcus DiDomenico. I had to go to three stores to find tarragon, as if there’d suddenly been a run on it. I did the chicken and rice and a green salad with toasted walnuts. I was all a-dither and to calm myself down, I blasted whatever was on the stereo, which turned out to be a disc from Doug’s twelve-CD compilation Led Zeppelin: The Definitive Collection. I ran around shout-singing the various songs, and as I was belting “Many times I lied,” I burned the walnuts and had to throw them out, and the kitchen smelled of burned nuts when I opened the door even though I’d been darting back and forth alternately opening the windows to get the smell out and closing them because it was so cold inside my teeth were chattering. I had not finished the vinaigrette when Marcus arrived, but I tried not to become mentally paralyzed by this fact. I tried to look on it with equanimity.

No doubt, I thought hopefully, he will want to wash up.

“I was going to get flowers, but I had too much stuff!” Marcus pronounced when I opened the door on him and his three enormous suitcases. Marcus DiDomenico was tall—six two or six three—and good-looking, by which I mean good-looking; you could have set him up on a blind date and told the other party that he was “good-looking,” and you would not have been lying or even exaggerating.

“Let me help you with those!” I said for some reason, and proceeded to drag the large roller bag inside and then go back for the others as Marcus glanced around the apartment with a bemused expression and then went over to the pair of windows opposite the door. “Back view,” he said with a wince when he lifted the shade and peered under it. “Too bad. But still—” He gave me a commiserating smile as I muscled and kicked and humped the last suitcase—an oversize duffel bag—over the threshold. “It’s great to be back in New York.”

I made some appropriate introductory remarks and showed him the alcove where he would be staying. “Make yourself at home!” I said and continued on in that widely recognized “hosting” vein. “I got out that luggage rack for you . . . the window sticks, but if you give it a good push, it’ll open right up!”

As I gave my welcoming spiel, Marcus, who had sat down on the alcove love seat that would fold out later into a bed, closed his eyes. He inhaled long and deep through his nose, as if he were starting to meditate. Ujjayi breathing it is called.

“Yeah, so we’ll all be sharing a bathroom,” I said faux apologetically to Marcus. “But Doug leaves pretty early, so it should be okay.” When I mentioned Gillian (“Wow, I miss her since she left. She and I—”), my houseguest took another long breath in through his nose, opened his eyes, and fixed me with the same look a young man had given me who dumped me in a diner just before his pancakes and eggs came. He even said more or less what the dumper had said: “I can’t deal with this right now.”

I had my line all ready. “Welp, I’ll leave you to it!” I said snappily, and I called back over my shoulder, “Dinner’ll be just a minute!”

It was clear I was going to excel in this hosting role. It was simply that I’d never been given a chance! After Marcus, I’d probably have a long string of guests—people would call me, impromptu, from Penn Station: Hey, I know this is last-minute, but any chance I can crash? Then people would probably start to refer houseguests to me of two or even three degrees of separation: I know you don’t know Veronica well, but her brother’s ex-girlfriend and I . . .

I hustled around in our little kitchen, my heart beating

erratically, making the salad dressing. I was so nervous my hand shook when I stirred the mustard into the olive oil and vinegar. When I checked the chicken, I saw to my dismay that it was browning far too fast. Just my luck! I ripped off a piece of tinfoil and covered it, patting it down around the sides of the Pyrex. Still, Marcus did not appear. I had put the cutlery, flatware, plates, and glasses on the folded-down Duncan Phyfe table we kept pushed up against the south, windowless wall of the combo living/dining room. This was so that when Marcus asked what he could do, there would be a nice, contained task for him of setting the table. But Marcus DiDomenico, I realized when I finally walked back through our bedroom to the alcove to check, had fallen asleep.

He slept and slept the way you can only sleep when you’re indulging the jet lag instead of fighting it. This is a strategy I do not recommend. In fact, it is one of my core principles to never give in to jet lag, but clearly Marcus and I did not share that value. I turned the oven off. I killed an hour, during which time I walked back to the alcove twice more and listened to his snoring from outside the door, clearing my throat loudly the first time, the second time pretending to trip and calling out “Oops!” and “Damn it!” I turned the stereo on at full volume “by accident.” “Whoopsie-daisy! Sorry about that!” I shouted. Eventually I carved the chicken, mistakenly hacking away at a thigh bone till I found the cartilage. When at last, around nine thirty that night, I heard Marcus moving around in the alcove, I jumped up and reheated everything, ferrying dishes back and forth from the counter to the microwave. Marcus emerged in cutoff sweatpants and a Hüsker Dü T-shirt with a royal case of bed head. I blushed, waiting for him to offer to help—listening for my cue to set him at ease, to say dismissively, “Don’t worry about it! Just relax!” Instead, he went and examined our bookshelves. He frowned as if something there unsettled him. “Can I borrow this?” he said, taking down my high-school copy of The Great Gatsby.

“Of course!” When he didn’t thank me—or respond at all— I cried, “I’ve read it! Keep it as long as you want!”

We sat down to dinner. “Will you do the honors?” I said, handing Marcus the bottle of red and then, with a flourish, the corkscrew.

He put the bottle in his crotch and tugged, then stood up and yanked. Half the cork came out; the other half had broken off and disintegrated into the wine. He splashed the wine into the two glasses I’d put out, filling them up to the tippy-top.

“That’s plenty!” I cried. “Jesus.”

“Why? Is there something wrong with this?” he said, taking a sip just as I was setting him at ease by saying, “Don’t worry about the cork—it’ll be fine!”

Staring blankly past me, Marcus shoveled food into his mouth for several minutes while I chattered away, filling the silence. First I told an anecdote about me and Gillian back in the “old” days. But I didn’t want to be rude and keep the conversation focused on me, so I said, “Gillian tells me you’re here to interview for a job? What sort of work do you do?”

He dragged his eyes away from the wall, chewing. “Me?”

I nodded, smiling warmly. “Yes! You. I mean—you! What do you, ah, do?”

“For a living?” “Yup! Yes.”

“I’m a management consultant.” “Ah, okay! ”

“Yeah, I’ve got this interview tomorrow . . . ” He frowned. “Ugh! I’m so sick of it!” he spit out suddenly.

“You’re—”

“I’m sick of all the fucking bullshit!”

“Ah, the bullshit! I see, I see . . . well, I certainly hear that.

From what I understand—”

“Do you have shoe polish in the house?”

Keys in the door jangled at this point, and Doug came in. “What’s that smell?” he called from our tiny foyer as he hung up his coat on the Ikea coat tree that he had assembled two nights ago after we retrieved the flat pack from the closet where it had lain for months. He came into the living/dining room, stopped, and did a double take. “Whoa—you cooked? No way! ”

“It’s just chicken,” I said evenly.

“Sweet! I didn’t know you were gonna cook! ” Doug turned to our guest. “Hey . . . Marcus, right? I’m Doug!” They shook hands, and I felt a little flutter of pride in my husband. I would have to strive to make sure Marcus did not feel left out, did not feel himself to be a third wheel in our happy-young-marrieds’ nest while he was alone and jobless—for the moment, anyway.

“Hiya, Doug! I heard about you! How’s it going, man?” “You want a beer?” Doug asked Marcus as he went to

the fridge.

“Um, actually, there’s red open,” I said.

Marcus stopped his glass halfway to his mouth and placed it to the side of his plate. “Yeah, a beer’d be better,” he said, and a look of misgiving crossed his face. Doug handed him an IPA. “Thanks, Doug! I appreciate it, man. Really glad you showed up, Douggie boy.” He pointed at the glass of wine and looked at me. “You want the rest of this?” It was the first time I noticed that he didn’t use my name.

“That’s okay,” I said primly. “I’m fine.”

*

Historically speaking, Doug likes no one. He is quick to smile and quick to laugh, but his easygoing demeanor masks a dismissiveness the likes of which I have never encountered in another person. So when he came to bed at midnight after talking and laughing with Marcus for more than an hour— while I lay awake, hearing just enough of every conversation to want to dispute its premise—I said, “Wait a minute. So you like him?” Marcus had not come into the alcove yet but I had made up the sofa bed for him so he wouldn’t have to stumble around in the dark.

“Oh God, no,” Doug said, but he chuckled to himself as he unbuttoned his shirt and placed it directly into the dry-cleaning bag—a house rule established by me a few months previous— and when I asked what was so funny, he said, “Sorry. Sorry! Just this thing we were—never mind.”

In the morning, Doug left early as he always does and I made coffee. Then, odd as it was, there was nothing for me to do but wait for Marcus to wake up. I had no plans until beginner yoga at eleven—I had been attending the beginner class for three years but still held out hope I would master the chaturanga and one day advance to “Open” level. I sipped my coffee and read the paper and did the crossword, and as I was looking up from writing rube in 19-across, I heard something move in the combination living/dining room and I screamed.

“Whoa there, Nellie!” said Marcus, who had evidently been sitting there the whole time. When I could breathe again and could assess the situation, I understood that he had slept on the living-room sofa, resting his head on the decorative pillows and using the decorative-accent-color (raspberry) pashmina throw as a blanket, which he now had wrapped around his naked shoulders and chest.

“Little too early in the morning to get excited!” he said. “The morning sets the tone for the whole day.”

“So, you . . . you slept out here?” I had jumped to my feet when he startled me and remained standing.

Marcus dog-eared the page of the book he was reading and tossed it aside. I saw that it was my high-school copy of Gatsby. He stretched, lazily scratched his stomach, and hooked the raspberry pashmina under his armpits. “Yeah. The other room was kinda bumming me out, so I came out here. This couch is rock-hard, though—yikes! You might want to have it restuffed.”

“I love this couch!” I said hotly. “Although,” I admitted, “I should never have bought it in blue.”

“Blue’s tough,” Marcus agreed. “I have this friend. Kelsey, see? And she’s awesome at decorating and colors and everything, so wherever I live, I just have her come over and tell me what to buy and where to put it, and my apartments always look awesome.”

“This is in Paris?” I said.

He gave me a look. “Naw. Just forget it.”

The pashmina still around his shoulders, he padded over, barefoot, in his boxers to the coffeemaker on the kitchen counter. I didn’t want to stare at his naked torso so I glanced at his legs. He had long, bandy surfer legs covered in golden hair, and surfer feet—long and curved—and he walked with that surfer walk, as if everything underfoot was ouchy hot sand. At any moment, I was sure, he would absently, conceitedly, touch his stomach and use a word like gnarly or perhaps nasty.

“Oh—I can get that,” I said as I quickly and bodily blocked his access to the mugs. “Here you go!” I plucked one from a row of them hanging on little hooks underneath the kitchen cupboard and handed it to him. “Do you take milk or sugar? Or we may have some cream in the fridge. I’m not sure. Doug likes half-and-half but he gets his coffee at work, so . . .”

He shook his head balefully. “Oh no, you don’t. No fucking way.”

“Okay, well, for breakfast, there’s yogurt, or I can make toast—”

“The dairy industry is up to some nasty shit. I gave that crap up years ago. You kidding? I don’t go near that lactose crap.” He overfilled the mug, and the coffee splashed out onto the counter. He leaned the pashmina into the spill and wiped with it using his elbow. Then he turned, bent over the coffee, and sipped off the top, no hands.

I cleared my throat and said tightly, “Okay, well, anyway, for food we’ve got—”

“Hey!” He straightened up and the pashmina slipped off and puddled on the floor, leaving him naked except for his boxers. “Can I use your phone?”

“Of course!” I said between gritted teeth as I snatched up the throw from the floor. “There’s one in the alcove. I mean, if that’s okay,” I added sarcastically, recalling his dislike for the alcove.

He looked surprised but then the surprise melted into a different expression—an expression of commiseration. He grasped my shoulder. “It’s o . . . kay. It’s okay. It’s gonna be all right, okay?” He put the coffee down on the counter and stepped behind me and began to knead my shoulders and the base of my neck. “Man, you’re so fuckin’ tense. You gotta relax! Life’s too short!”

He took his coffee mug down the hall, spilling all the way, and after a couple of minutes, I heard him shouting and laughing. “But that’s insane! ” Later, as I made my bed, I heard “Fucking kid. Ding. Me!” And when I stood outside the alcove one last time, he was saying, “Uh-huh, yup, okay, got it,” in the tone of someone who is jotting down instructions. I poured myself another cup of coffee and drained it, tidied up the living-room sofa, tried to sponge the coffee off the pashmina, and plumped the decorative pillows back into place. After forty-five minutes my houseguest was still on the phone. After an hour, I picked up the receiver in the kitchen and said, “Wait—what? Marcus? You’re still on? Sorry! I hadn’t realized that. I can make my call later.”

“Oh,” he said coldly. “Okay.”

I went to beginner yoga to give him time to get out of the apartment, and in class I stood in the back. It wasn’t the usual teacher but some overly ambitious young woman who heckled us through thirty or forty sun salutations. By about minute twenty, I started saying audibly, “What’s she trying to do, kill us?” and “As far as I know, the Ramamani didn’t believe in torture! ”

Fearing over-caffeination, I lingered at the studio, nursed a lemon verbena in an off-brand coffee shop, and ran a couple of errands. At this point, I figured, there could be no doubt that Marcus would have left the apartment. He had mentioned a job interview. It was after noon now. Job interviews struck me as morning kinds of appointments generally speaking. It seemed safe to return. If he was still there . . . well, tough luck. It was my apartment. I wasn’t going to be guested out of it.

When I stepped into the apartment, I tripped over something and fell to the floor with my shopping bags. It was Marcus’s huge roller suitcase, now, inexplicably, back in the living room, and not only back but open on the floor and spewing clothes and shoes. Before I could get off the floor, Marcus appeared, still naked but for his boxers—a new pair, I noticed, with a panting-beagle motif. He winced as if he were embarrassed to say what he was about to say: “Um . . . I never did get that shoe polish.”

“I asked Doug!” I said, getting to my knees. “We don’t have any here. He’s been getting his done at work.” I hesitated. “But you know what? I’ll run out and buy some. It’d be good for us to have some around. What color do you need? Black? Brown?” I asked. “Cordovan?” I added for some shoeshine humor, which I don’t think he picked up on.

He didn’t answer this. “What size does Doug wear?” he asked. “Eleven? No—eleven and a half.” I got laboriously to my feet using the bags as ballast, then had to get back down on my hands and knees and finally lie down flat to retrieve an orange

that had spilled out of one of the bags.

He addressed me as I was lying on the floor reaching under a chair for the orange. “Yeah? Those might actually fit.”

“So, you need to borrow some shoes?” I said pedantically as I got to my feet.

“Only if you can find them in a hurry. Kinda . . . chop-chop situation, you know?”

I found it highly amusing that he didn’t think I was up to this hosting gauntlet he had thrown down. I left the groceries on the counter and, still in my coat, went to our bedroom closet and immediately laid my hands on Doug’s backup pair of dress shoes.

“Voilà!” I said triumphantly, handing them to Marcus, who disappeared into the alcove. I unpacked the groceries, leaving him alone to get ready, but when he didn’t emerge after a few minutes, I walked back to the bedroom and called, “So what time is your interview?” Nothing like a little passive-aggression to get people to do your bidding, I figured, taking a page from my dry cleaner.

He opened the door, dressed in a rumpled suit with no tie as of yet. Just as I was making the mental leap of conceiving of management consulting as a more casual industry than I had envisioned, Marcus replied, “One p.m.”

“One?” I was aghast. “But it’s a quarter of ! One?” I repeated. “Is it close? Are you kidding me? How far do you have to go?”

He closed his eyes and did the long, slow nose inhalation again.

“You’re gonna be late! ” I said remorselessly. There was no use sugarcoating it. Despite my limited success in the workplace (sex on the copy machine: xeroxed cheeks), I had gathered that corporate entities cared about things like punctuality. “You at least can’t be late! Jesus Christ!”

Marcus put his hands over his ears. He sat down on the previously scorned love seat and began to sing, “‘Happy birthday to you! Happy birthday’—” I gripped one of his hands and pried it away from his ear.

“You are going to miss the fucking interview!”

“‘Happy birthday, dear’ . . . ” He stopped and pressed his fists to his eyes. “My suit!” came a muffled cry. “It’s fucking wrinkled!”

“Oh my God! ” I got the address out of him—it was somewhere near Columbus Circle.

Of course I told him it was far too late to think about ironing. Of course I explained that it was better to be fifteen minutes late in a rumpled suit than half an hour late in a pressed one, but in the meantime the argument itself was wasting precious time. He stripped down to his shirt and boxers and I flew off with the jacket and pants. The ironing board was jammed into our one storage closet—though less jammed since we’d relieved it of the flat-pack Ikea coat tree—and when I yanked it out, a dozen things fell to the floor: an abandoned needlepoint project of a spouting whale; The South Beach Diet: Supercharged; a number of translucent plastic shoe-organizing drawers, currently empty, so not organizing anything, contributing, in fact, to the disorganization. The irony of this did not escape me, but I had time only for ironing just then, and not for its literary word-cousin. I set up the board in the hall outside the alcove and barked out instructions as I ironed: “Get your tie on and comb your hair!” When I checked the bottom of the iron to make sure it wasn’t too hot, I burned my fingers. I started on the pants, going, “Ow! Fuck! Ow! Fuck!”

Thank God I am a wonderful ironer. I can do pleats and Peter Pan collars and ruching like nobody’s business. The rescue-cat crowd, needless to say, lacks this skill entirely—a fact that brought a condescending smile to my lips when I recalled it. They have no use for an iron and ironing board; indeed, many of them do not own either, as I discovered when I wanted to quick-press a pocket flap on a cotton blazer I had worn to a garden party in deep Brooklyn without realizing the pocket had dried folded.

By 12:57, Marcus was dressed. He had neglected to tie his tie and I had to do it for him. Perhaps he thought he would charm the interviewer with a rumpled louche appearance, but I felt this strategy was a risky one. I’m not sure what he had done in the several minutes in which I ironed the suit, to be honest. As I was reaching up and standing on my tiptoes to push the knot into place, I felt his lips on my hair; however, I ignored this because I had noticed that it was the same tie as one of Doug’s. I addressed him frankly. “Are you a graduate of Davenport College at Yale University?”

“No,” Marcus said. “I see.”

“Shit! Shit! Shit! Shit!” he exclaimed, feeling in his pockets. “I don’t have any cash for the cab!”

You will have gathered that this was before New York taxis took credit cards or used phone apps or allowed any form of payment other than cash. I had previously been caught out myself in a similar fashion so I called reassuringly—I was already halfway to the kitchen—“It’s okay! I keep a stash of cash handy for just this reason!” I pressed a second twenty-dollar bill on him after the first, just in case he got into traffic or got lost. He could thank me and repay me later even if—as I feared— he did not get the job.

He rushed out the door and I flopped down onto the sofa as if I would never rise again, but just as I was lying back, putting my feet up on the coffee table, and reaching for Gatsby so I could smooth out the dog ears—not to worry, I planned to put a pencil in the book to mark his place—there was a peremptory knocking on the door.

I let out a scream of agitation as I rose from the sofa. When I opened the door, he didn’t look me in the eye but only stood there mumbling to himself, “I can’t do this. I cannot do this! I haven’t interviewed in years. Years! Do you hear me?” This last question was directed to himself, and I wondered passingly whether he suffered from what used to be known as multiple personality disorder. That would explain a lot, I thought. A hell of a lot. But I took hold of his shoulders and physically spun him around and pushed him down the hall.

I trailed him right to the elevator. I was about to go back but thought better of it and waited until the elevator arrived, my arms folded across my chest in a classic pose of defense while he quietly cursed himself: “You fucking idiot. You fucking, fucking, fucking idiot. You always fucking do this! Sometimes I really hate you!” The elevator came; he got in. And the doors closed on Marcus DiDomenico staring forward with a frightful intensity.

After organizing Marcus’s suitcase sufficiently so I could close it and drag it back down to the alcove, I lay comatose on the couch. In point of fact I was waiting for the cable guy, who, two hours after the appointed window, still had not shown up. My houseguest, I understood now, was in a precarious mental state. Fragile to begin with, he was clearly losing his shit. I considered calling Gillian to discuss him, but I couldn’t muster the energy and, truth be told, I shied away from talking about someone behind his back when he was still under my roof. I only had to get through another day or two—he was slated to leave on Tuesday or Wednesday, latest. As the day wore on, I considered the kind of pressure he was under and I steeled myself to listen supportively when he got back. As the day wore on, I worried he was lost. As the day wore on, I opened the door several times and listened, as if I would hear him lurking in the hallway or taking the back stairs up. I worried that he had been so agitated he had blown off the interview and was now too ashamed to admit it. I worried all kinds of things.

At five thirty, I called Doug. After some preliminary back-and-forth, I said casually, as if it were an afterthought, “It’s a bit weird, but I haven’t heard from Marcus all day.” I explained how he’d gone off, late and worried, for the interview. “I guess I thought he’d either be home by now or else I’d hear from him. I’ll have to figure out a way to leave keys because”—I sounded the kicker triumphantly—“I actually have plans tonight. I’m meeting Kelly for drinks.” Kelly McMahon was a childhood friend of mine, briefly in New York for an accountants’ conference. “It’s been on the books for weeks.”

“Oh!” said Doug. “Oh.” “What?”

“Well, it’s just—I’ve heard from him. He and I—” “You’ve heard from him?”

“Yeah!” said my husband. “He called me to see if I wanted to meet up for a drink.”

“He did? You mean tonight?” “Yeah—we’re meeting in an hour.”

“Oh. Okay. I see,” I said. Then I added, “Great!”

“I figured you’d be glad if I got him out of the house for an hour.”

“For sure. I mean—definitely. Definitely.”

“Cool. Apparently the interview went really well, by the way—they want him to come back for another round.”

“Really?” This gave me pause. “I’m kind of surprised, to be honest, given how late he was,” I said by way of explanation— not wanting to impugn Marcus’s actual skills as a management consultant, of which I had no knowledge.

“Weird—he didn’t mention that,” Doug said. “Told me he cabbed over a couple hours early so he could walk around and check out Radio City.”

I hesitated. “Well—have fun tonight!” I said. “You too!” said Doug. “Tell Kelly I say hi!”

The truth was, despite having grown up on the same street in the same small town, Kelly and I didn’t have all that much to say to each other. Before becoming a certified public accountant— a “CPA,” as they call themselves—she had spent several years in a cult to which she had twice tried to recruit me. I could see a couple of benefits of being in a cult—any cult, let alone this particular cult, where the food, apparently, set the standard for farm-to-table—but as I said to her then, “I guess I prefer life on the outside.” Since the year she was deprogrammed, I had felt it would be untoward to go there conversationally; at the same time, I didn’t know much about accounting. My usual opener when we met for drinks was “So . . . how are things at the Big Five?” I could never remember which big firm she worked at but I wanted her to know that I knew she was not working at a small accounting firm that people had never heard of. She, meanwhile, with surprising tenacity, usually spent these rendezvous trying to elicit an explanation from me as to what I did all day. I sometimes felt she had been sent by our small hometown to extract information about me and bring it back. Tonight, feeling my time management was my own business, I kept ordering appetizers whenever she lobbed a direct question, and pretty soon we had eaten three sliders apiece, a basket of popcorn shrimp, and a mini–goat cheese soufflé and I felt I had to shut it down or be compelled to order the ubiquitous hummus or “guac,” which I suspected would be of an inferior quality at the Irish pub where we had met.

As I came up the stairs to our floor, I could hear uproarious laughter coming from my apartment. My smile may have been a bit uncertain when I went in, given that I’d pictured awkward conversation over takeout while they watched the basketball game on network TV, the only channels we got at the moment while we awaited the arrival of the cable guy. But whatever confusion I had about what the two of them were finding so incapacitatingly funny was cleared up the minute I shut the door behind me and heard Doug saying, “So, Donnegan just says, ‘Oops!’” I was tempted to turn around and go right back out, maybe kill an hour drinking alone at a dive bar—that’s how much I didn’t feel like hearing the Donnegan story.

I stepped into the room from the foyer. Marcus was lying facedown on the floor in his now extremely wrinkled suit pants and shirt, also now untucked and unbuttoned, laughing so hard his ribs were shaking. He was pounding the floor. “Oops!” Doug repeated. “So the guy just says, ‘Oops!’” Doug made a visible attempt to control himself as I came in, but when he tried to say, “Hi, hon,” he cracked up, took a sip of beer to stop himself, and proceeded to spew it all over the coffee table where my guest-friendly large-format photography books were stacked. Empty beer bottles were strewn across the coffee table and kitchen counter and there was a stack of pizza boxes on the floor by the couch.

“Looks like you guys are having fun!” I said, shooting dagger eyes at Doug. “I guess I’ll just crash early.”

“Sounds good, hon!” Seemingly chastened, Doug asked how my drinks with Kelly were.

“Well, you know Kelly. She—” I started, but I was cut off by Marcus erupting again into his guffaw.

Struggling to speak, he pushed himself to sit up. “So he just—he just—he just says, ‘Oops!’ ”

I stood there waiting for him and Doug to stop laughing hysterically.

When I could get a word in, I said angelically to Marcus, “Hey, how’d the shoes work out, by the way?” I was so prepared to say It’s okay, really—don’t worry about it that when he opened his mouth to speak, these words were out of my mouth before I heard what he was actually saying, which was “To be honest, a little tight. Turns out I’m more of a twelve than an eleven and a half.”

My response sat strangely in the air, especially given how solicitous of our guest I had been thus far. “Well, hon, it’s not okay if he can’t walk in them!” Doug said awkwardly.

I looked at him in silence. I headed for the hall, then paused. “The cable guy never showed.” I added pleasantly, “I waited all day.”

“He didn’t? Damn it!”

“I guess I’ll just have to wait tomorrow too.” “Sorry, hon,” Doug said, looking glum.

“Oh, hang on a minute, Doug,” Marcus piped up. “Did you say cable guy? As in Time Warner?”

Doug nodded. “Yeah, he was supposed to come and replace the router.”

“Oh, I talked to them! A couple of times!” “Oh, did you?”

Marcus laced his fingers together, turned his palms out, and stretched his arms up straight. “Yeah, it was some call-waiting bullshit and I was on to Brazil and I couldn’t deal, so the third time, I just blew it off.”

“Sure, sure,” said Doug. He took a sip of his beer. “No big deal!”

“Ah-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha! He just says, ‘Oops’? Ah-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha.”

I retreated stonily to the bedroom, where I lay awake fuming. I hated the Donnegan story—hated it. It was an offensive story. But to be honest, that wasn’t the reason I hated it.

Mike Donnegan was one of Doug’s suite mates in college and one of the three guys he shared a low-rent apartment with in his two years in the city prior to business school. A pithy fellow by all accounts, Donnegan was known for many bons mots, including his oft-quoted TGIF variation: “I’m gonna rock out with my cock out.” Donnegan had bedded so many women in his teens and twenties that “Wait, did you do Donnegan?” was an icebreaker that could be heard in the early ’90s among women meeting one another at parties from SoHo to Doormandy. Donnegan was so promiscuous, there were even rescue-cat women who had slept with him despite the wide chasm between Donnegan’s and their sensibilities. Indeed, the very best parties of my twenties were the ones that both Donnegan and the rescue-cat crowd attended. Suffice it to say simply that at these parties, the shit went down. But back to Donnegan. Donnegan had been at it so long he couldn’t remember how or when he’d lost his virginity. He was like one of those kids who grow up on horse farms—there had never been a time when Donnegan couldn’t ride. In college, Donnegan had famously gone from one woman’s bed to another’s in the same night and then back again. In his twenties, Donnegan had conducted an affair with a married B-list celebrity that made the Post and the Daily News. And so on. But to get to the story: In college, Donnegan liked to get young women to have anal sex with him—it was a known predilection he had, among many others. One young woman was, despite Donnegan’s many charms, resistant to the idea. So Donnegan, coming home one night crowing—Donnegan always crowed, gleefully—shared a piece of advice with the guys: “Yeah, so you just pretend you wanna do it doggy-style, and then you go, ‘Oops!’ ”

That was the story.

It was a stupid story. The very stupidest. The anatomical facts did not support it. But neither the rapey dénouement nor the suspension of disbelief the story required was the source of my irritation with the Donnegan story. The secret reason I loathed it was that my husband loved it. Indeed, Doug looked for any opportunity to recount it. Every retelling was nails on a marital chalkboard for me. I began to fantasize about ways to get him to stop telling it. For instance, I knew he would not have told it if I had slept with Donnegan. The story would, in that case, have been too close for comfort. But by the skin of my teeth, I had not slept with Donnegan. Indeed, the night I came closest to sleeping with Donnegan was the night I met Doug. So there was no way to keep Doug from telling it and telling it and telling it, to not hear the admiring chuckle that punctuated it, to not note the blissful, vicarious chortle of every married man from FiDi to Upper Fifth who lovingly repeated the Donnegan story.

A little while ago I came upon a list that I’d made—on a piece of paper; it was before anyone used a phone for that kind of thing—entitled “The Top Ten Transgressions of Marcus DiDomenico.” His failing to thank me for the use of my husband’s shoes and for ironing his suit pre-interview, his blowing off our cable appointment, which took seven days to reschedule— none of those even made the list. The list, you see, was composed entirely of incidents from the second half of Marcus’s stay, all of which vanquished the first-half offenses so thoroughly as to make them seem like sun salutations in beginner yoga. The second half of his stay officially started the Wednesday after he arrived. I cleared my throat as he was pouring his coffee and asked him what time he’d be heading out. “Oh, you mean to get some air?” No, I said, and reminded him that he was leaving later that day. “Ha! Right! What? How would that even work?” was all he said. “Doug and I have plans to go to Monster Trucks Friday night!”

In the second half of his stay, Marcus violated the guest/ host code in so many ways, it is hard to recall all of them. He took daily baths and failed to drain the water. He ran the dishwasher with dishwashing liquid in it. He exploded his takeout Chinese in the microwave and left it there. He opened the bottle of Romanée Conti we had put away for when our first child was born and used it to cook with but then fed the dinner he made to a homeless man who lived on our street. After he gave the man dinner, he brought Beppe up to our apartment to take a shower. “But . . . ” I murmured. “I don’t have any towels . . .”

“He can use my towels,” Marcus said tartly. “You fucking liberals—you’re all the same. You preach charity but then you don’t want a guy like Beppe here to get your towels dirty!”

I did as I was told; I always did now. I had become, in the space of a week, like one of those mothers of four—chaos didn’t faze me. I could get dinner on the table in half an hour. I no longer complained about the faults I found with my cleaning woman; Marcus didn’t like faultfinding. “I say, just do it your fucking self and shut up about it!” But that wasn’t all. Another day when Marcus came home—apparently from an interview, but I had given up trying to parse how he spent his days—he yelled from the alcove where he still stored some of his things even though he didn’t sleep there that he needed me. “I’m cooking!” I called back. “I don’t want to burn this!”

A few minutes later he appeared in the kitchen, naked but for a towel around his waist. “Look, I’m in pain here. I need you to rub this on my back and you’re like, ‘I’m cooking’? What the fuck?” Without another word, he handed me the bottle of Bengay.

“Where do you want it?” “Lower back.”

I started to rub it into his back.

“Lower . . . lower! Jesus—” He craned his neck around. “Are you hearing me?”

“I’ve reached your towel,” I said stiffly.

“Oh my God! Are you one of these people who’re so uncomfortable with the body, you can’t cope with a flash of butt crack?” He whipped off his towel and I found myself massaging the Bengay into his butt cheeks. I tried to rub it in with a confident hand.

Wouldn’t it be nice if Doug arrived home just now? I thought. Though in truth I wondered if it would have any effect on him—I wondered if he would even notice. For days now, I had seen my husband down a long narrow tunnel; I had no direct access to him at all, no line in, and the distance never shortened. He had started sleeping in the alcove so as not to awaken me when he came to bed at one or two a.m. In the mornings, I slept as if I were the one who was hungover—he would be gone before I could rouse myself. Needless to say, the Schedule had fallen completely by the wayside. When the cable guy finally did show up, I brought him a seltzer water, offered him bridge mix, and hung over him as he worked, but the moment he finished installing the new router, Marcus arrived home and engaged him in a conversation about upgrading our package to include HBO and Showtime. And by that point, I had to get dinner started.

I dreamed that I was in a desert being pursued by monsters, and Doug was so far ahead of me, he couldn’t hear me screaming. When I awoke, I was silent-shouting his name. I had started to leave early for beginner yoga—to walk the streets for hours just to be out of the apartment. That morning I dressed in my athleisure outfit and made coffee, working as quickly and silently as possible, but I dropped a mug, and a minute later Marcus sat up on the sofa in the combination living/ dining room. “Listen,” he said. “It’s kinda been a while for me . . . and I was thinking maybe you could just, you know . . . ” He turned his palms over and gestured to his nether regions with both hands.

I said: “Are you asking me to perform fellatio on you, Marcus?”

“Fellatio!” he fairly screamed. “Who said anything about fellatio? Jesus! I was just thinking maybe a hand job!”

As he was saying the words hand job, the apartment door banged open, and Doug stood there framed in the doorway. “I forgot my keys,” he said. He turned to Marcus, who suddenly looked rather sheepish. “You’re going to have to leave, Marcus,” said Doug.

“But she—”

“You’ve overstayed your welcome,” my husband said distinctly. “And now it’s time to go.”

He waited while Marcus took a twenty-minute shower, singing the chorus of “Rhiannon” over and over, each time saying, in place of heaven, “‘Would you stay if she promised you leather?’ ” We had a polite conversation, Doug and I, while we waited, about the many couplings and breakups Fleetwood Mac had experienced. We waited while Marcus tried on and rejected different outfits, then while he made calls and stubbed his toe on the alcove foldout. “Ow! Motherfucker!” we heard. “Time to throw this piece of shit out! ” At last Marcus emerged, wearing his suit jacket over short running shorts and a T-shirt, grasping Doug’s Yale tie in his fist. “Okay if I borrow this, Dooger?”

I was about to protest, but Doug put up his hand to stop me. “Sure, Marcus. Just take it.”

He escorted Marcus down to the curb after heaving two of his three huge suitcases out to the elevator. I went back to the alcove and surveyed the room. He had left a wine bottle with a centimeter of wine remaining in it; Gatsby splayed open with, I saw, picking it up, half of the title page torn off (I later glimpsed it in the wastebasket—he had used it to throw out gum); and a piece of my monogrammed stationery on which he’d made a flowchart that mentioned new york, tangiers, and the words distance to border without capitalization or punctuation.

Doug didn’t come back upstairs after seeing Marcus off. He went right to work, so I didn’t see him till that night. I spent the day in one of those detached yet meditative states they’re always talking about in yoga but that I’d never been able to come close to achieving. I didn’t think of much at all. I tidied and cleaned and made a simple supper of sausages, lentils, and steamed broccoli. Doug came home, and we ate it in silence, alternately sipping from our wine and our water. About halfway through the meal, we both suddenly spoke at once.

“I really hope he didn’t forget—”

“God, I wish I’d told him—”

That was sufficiently embarrassing that we both drained our wine in a hurry. And after another glass or two, I began to giggle for no particular reason and found I couldn’t stop. Doug did a Marcus imitation that was so good, it was uncanny—he got the stretch and the walk and the stare. Like an old married couple, we didn’t start making out till we got into bed. “Now, according to the Schedule, we’re not actually, I mean technically, supposed to—” I couldn’t stop myself from saying, but I found I was too distracted to finish the sentence. That’s when I heard Doug say, “Oops!”

__________________________________

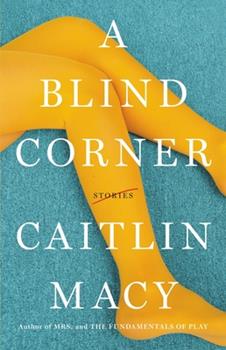

Excerpted from A Blind Corner by Caitlin Macy. Copyright © 2022. Available from Little, Brown, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc..