The Surprising Power of Piet Mondrian’s Lesser-Known Early Paintings

Nicholas Fox Weber Reflects on Mondrian’s Still Lifes and Black-and-White Work

Approaching the age of twenty, Mondrian painted his most impressive painting to date. It was a still life of a dead hare. The animal hanging from its right hind leg is a feat of verisimilitude. The setting—the space above a wooden plank that recedes into a black background—is a triumph of austere elegance. The contrast between the luminous subject and the rich black presages Mondrian’s later abstractions.

The canvas belongs above all to the tradition of Dutch still lifes as well as to pictures of freshly killed game by the French eighteenth-century painter Jean Siméon Chardin, but it is not a mere pastiche. It has a zing that goes far beyond the slavishness of a copy.

The sharp focus with which Mondrian renders the hare, and the elegance of the matte black background, have assurance without arrogance. With his renewed determination to be a painter, Mondrian had become his own man and developed his capacity to paint with a punch that energizes the viewer.

Mondrian’s confidence shines in several paintings of fruit baskets and earthenware pitchers that he made that year. Adhering to the same historical traditions as when he painted the hanging game, he focused on the art of the past that was the most tough and truthful, imbuing his own painting with that same rigor and candor. He had already developed the attitude toward art-making he would have lifelong.

The young painter concentrated his subject, reduced the elements, and eliminated anything superfluous. He made the straw of a basket the perfect blend of supple and taut, and the skin of an onion microscopically thin. Having mastered weightiness as well as ethereality, he rendered a stone slab so that it is heavy and firm.

He would not have dreamed of dipping his hat toward the lyricism and prettiness that were the vogue of the era, and kept anything personal invisible.

He would not have dreamed of dipping his hat toward the lyricism and prettiness that were the vogue of the era, and kept anything personal invisible. The only revelation of himself is his consuming love for the act of painting.

Unsurprisingly, when these canvases were exhibited the following year, a critic in the Utrecht daily paper disapproved of Mondrian’s straightforwardness. The anonymous “expert” opined, “He can…do more than he gives us here. There is something lacking which we cannot do without: poetry, mood.”

Mondrian was pitted against that prevailing taste. Even though he was training to pass exams that upheld the current standards for artistic know-how, he refused to use the devices of Romantic painting requisite to garner critical approval. The overt sentimentality and gratuitous atmospheric effects demanded by the preferred style of the era were anathema to him.

Mondrian had to be tough to remain so independent and out of sync with the current taste. To be accused of lacking poetry, and of not giving enough of himself, were stinging insults.

But what he rejected was not the central issue. Mondrian’s discovery of a vision he could trust provided solace in his lonely life.

He had the force within him to be undaunted by the slams. He needed it. Mondrian would wait many years until his unusual choices found an audience that recognized just how poetic they actually were.

He was lucky to have his father’s stubbornness and tenacity. Mondrian’s goals were elusive, but he would not dream of wavering in his quest for a new form of spiritual beauty.

*

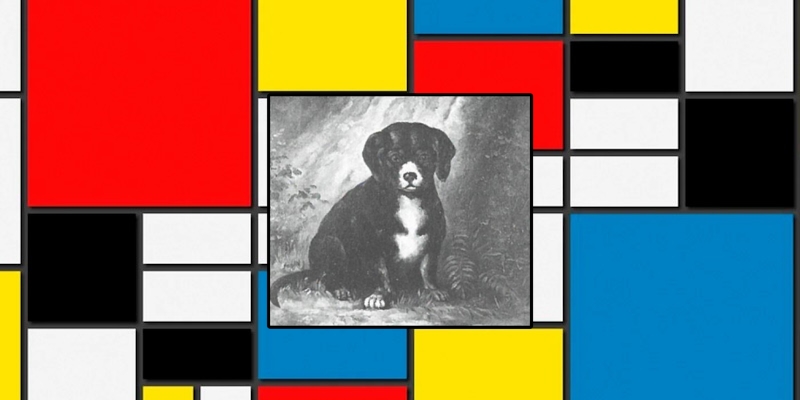

In November 1891, Mondrian made a painting of a puppy that is an anomaly—one of his works where few people would guess the authorship. The subject, by its very nature, assumes a quality of “cuteness,” even adorability. Still, the nineteen-year-old artist approached it with the same boldness as his still lifes.

In its tender rendering of a fetching animal, this small canvas exudes the sheer warmth that was vital, lifelong, to Mondrian’s work. The simple happiness it provides is all the more remarkable given the absence of the sort of playful joy afforded by household pets in Mondrian’s own childhood.

Puppy, simply and eloquently, is a reminder that the sight of things—whether young dogs or abstract patterns—can penetrate our souls.

The young dog’s portrait is enlivened by qualities that Mondrian developed in a radically different form in his abstractions thirty years later. What is remarkable is that he already recognized them as a way to impart wellbeing to the viewer.

The crisp black of most of the dog’s hair, which shines brilliantly in the sunlight coming from the upper right, plays against the bright white of his muzzle, chest, and paws. It is the same counterpoint that will occur in Mondrian’s spectacular gridded diamond compositions and other geometric constructions.

What was probably a commissioned portrait of someone’s pet proves that from the start Mondrian was viscerally charged by the interplay of neatly confined precincts of black and white.

Puppy, simply and eloquently, is a reminder that the sight of things—whether young dogs or abstract patterns—can penetrate our souls. Looking begets enchantment. Analysis is a secondary issue.

We don’t know precisely why the contrast of black and white or the appearance of puppies elevates the human spirit, but when articulated properly, they do so.

Nicholas Fox Weber

Nicholas Fox Weber has been the executive director of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation for four decades. He is the author of iBauhaus, Le Corbusier, Balthus: A Biography, Patron Saints, and Mondrian. He lives in Connecticut, Paris, and Ireland.