Let the impulse dictate the logic.

This was the gambler’s creed, his formal statement of belief.

They sat waiting in front of the superscreen TV. Diane Lucas and Max Stenner. The man had a history of big bets on sporting events and this was the final game of the football season, American football, two teams, eleven players each team, rectangular field one hundred yards long, goal lines and goal posts at either end, the national anthem sung by a semi-celebrity, six U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds streaking over the stadium.

Max was accustomed to being sedentary, attached to a surface, his armchair, sitting, watching, cursing silently when the field goal fails or the fumble occurs. The curse was visible in his slit eyes, right eye nearly shut, but depending on the game situation and the size of the wager, it might become a full-face profanity, a life regret, lips tight, chin quivering slightly, the wrinkle near the nose tending to lengthen. Not a single word, just this tension, and the right hand moving to the left forearm to scratch anthropoidally, primate style, fingers digging into flesh.

On this day, Super Bowl LVI in the year 2022, Diane was seated in the rocker five feet from Max, and between and behind them was her former student Martin, early thirties, bent slightly forward in a kitchen chair.

Commercials, station breaks, pregame babble.

Max was accustomed to being sedentary, attached to a surface, his armchair, sitting, watching, cursing silently when the field goal fails or the fumble occurs.

Max, speaking over his shoulder, “The money is always there, the point spread, the bet itself. But consciously I recognize a split. Whatever happens on the field I have the point spread secured in mind but not the bet itself.”

“Big dollars. But the actual amount,” Diane said, “is a number he keeps to himself. It is sacred territory. I am waiting for him to die first so he can tell me in his final breath how much money he has pissed away in the years of our something-or-other partnership.”

“Ask her how many years.” The young man said nothing.

“Thirty-seven years,” Diane said. “Not unhappily but in states of dire routine, two people so clutched together that the day is coming when each of us will forget the other’s name.”

A stream of commercials appeared and Diane looked at Max. Beer, whiskey, peanuts, soap and soda. She turned toward the young man.

She said, “Max doesn’t stop watching. He becomes a consumer who had no intention of buying something. One hundred commercials in the next three or four hours.”

“I watch them.”

“He doesn’t laugh or cry. But he watches.”

Two other chairs, flanking the couple, ready for the latecomers.

A stream of commercials appeared and Diane looked at Max. Beer, whiskey, peanuts, soap and soda. She turned toward the young man.

Martin was always on time, neatly dressed, clean shaven, living alone in the Bronx where he taught high school physics and walked the streets unseen. It was a charter school, gifted students, and he was their semi-eccentric guide into the dense wonders of their subject.

“Halftime maybe I eat something,” Max said. “But I keep on watching.”

“He also listens.”

“I watch and I listen.” “The sound down low.” “Like it is now,” Max said. “We can talk.”

“We talk, we listen, we eat, we drink, we watch.”

For the past year Diane has been telling the young man to return to earth. He barely occupied a chair, seemed only fitfully present, an original cliché, different from others, not a predictable or superficial figure but a man lost in his compulsive study of Einstein’s 1912 Manuscript on the Special Theory of Relativity.

He tended to fall into a pale trance. Was this a sickness, a condition?

Onscreen an announcer and a former coach discussed the two quarterbacks. Max liked to complain about the way in which pro football has been reduced to two players, easier to deal with than the ever-shuffling units.

The opening kickoff was one commercial away.

Max liked to complain about the way in which pro football has been reduced to two players, easier to deal with than the ever-shuffling units.

Max stood and rotated his upper body, this way and that, as far as it would go, feet firmly in place, and then looked straight ahead for about ten seconds. When he sat, Diane nodded as if allowing the proceedings onscreen to continue as planned.

The camera swept the crowd.

She said, “Imagine being there. Planted in a seat somewhere in the higher reaches of the stadium. What’s the stadium called? Which corporation or product is it named after?”

She raised an arm, indicating a pause while she thought of a name for the stadium.

“The Benzedrex Nasal Decongestant Memorial Coliseum.”

Max made a gesture of applause, hands not quite touching. He wanted to know where the others were, whether their flight was delayed, whether traffic was the problem, and will they bring something to eat and drink at halftime.

__________________________________

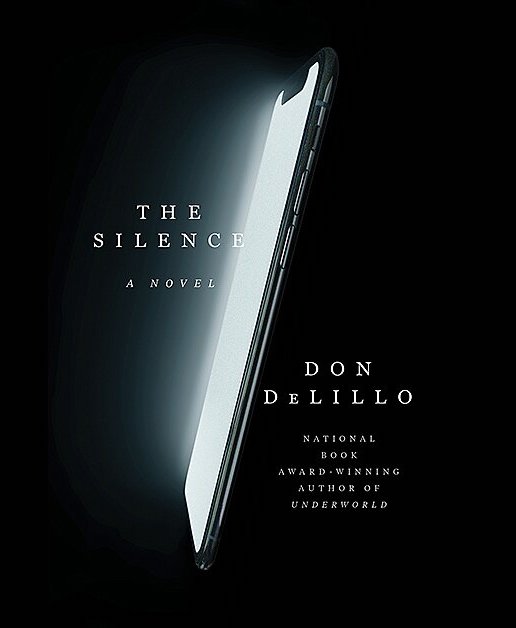

Excerpted from The Silence by Don DeLillo. Excerpted with the permission of Scribner. Copyright © 2020 by Don DeLillo.